Sing me back home with a song I used to hear

Make all my memories come alive

Take me away and turn back the years

Sing me back home before I die

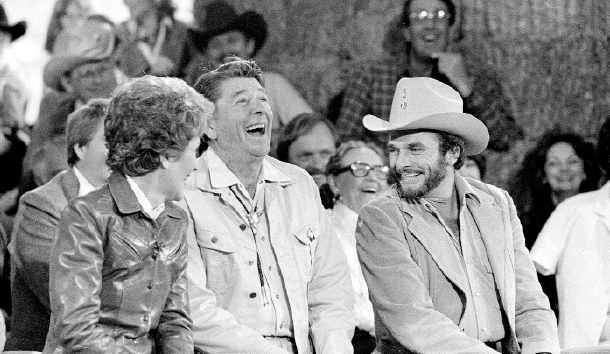

Merle Haggard was a real American. At its best, his music was folk art, Americana poetry, each song capturing a snapshot of his people’s story. There was nothing phony about Haggard, and his music and songwriting showed what country music can be—honest and authentic, gritty and harsh, soulful and touching. His work was “roots music” before there was a term for it, music that displayed all the pain and joy, the pride and regret, the sins and the virtues of his people and their hardscrabble, Dust Bowl lives. The word artist has become a particularly trite cliché used of every pop entertainer who comes along these days, but in Haggard’s case, such a description was appropriate. Merle Haggard once said that what the public really wanted was the “most rare commodity in the world—honesty,” and that’s what he gave us. “The Hag” was dubbed the “poet of the common man,” a working-class boy who went wrong and found his way back through his music. He was 79 when he passed away of pneumonia in Palo Cedro, California.

Before he was born, Merle Haggard’s family left Oklahoma in 1935 after a fire destroyed their barn. Jim Haggard and his wife, Flossie, took their family west to Oildale, California, following the path of many other Okies, Arkies, and Texans who were forced to migrate during the Great Depression. Jim found work as a carpenter for the Santa Fe Railroad and, like many others in his situation, converted an old boxcar into a home for his family. Merle’s sister, Lilian Haggard Rae, remembered the old house fondly as a “wonderful home to live in,” with thick walls that kept the house cool in summer and warm in winter. In those days, Oildale was a collection of camps and makeshift homes near Bakersfield, the town with which Merle and his music would be strongly associated, just as images of train engines, boxcars, and fugitive lives would be. Like his sister Lilian, Merle was attached to the old place, an attachment evident in songs like “Old Tanker Train”:

The old tanker train from down on the river

In Southern Pacific and Santa Fe names

Would rumble and rattle the old boxcar we lived in

And I was a kid and I loved that old train

Loaded with crude oil, headed for town

The boxcar would tremble from the top to the ground

And my mother could feel it even before it came

“Get up son to the window—here comes the old train”

In his 1999 autobiography, My House of Memories, Merle wrote of his disappointment that the old house was deteriorating, relieved only that his parents weren’t around to see what had become of their “wood and stucco jewel box.”

From my checkered past I can always bring back

The memories we felt in that home by the track

Jim Haggard played fiddle and guitar at schoolhouse dances and other social events back in Oklahoma, and Merle thankfully inherited his father’s love for music, though he later recalled it was his mother who showed him “a couple of chords” on an old guitar his brother had brought home, the boy teaching himself thereafter. Merle was close to his father, and Jim Haggard’s death from a brain tumor when Merle was nine nearly wrecked the boy’s life. Flossie Haggard, a devout member of the Church of Christ, got a job as a bookkeeper to support the family, while a distraught Merle rebelled. Merle felt the tug of those rail cars rumbling by and hopped on a freight train when he was just 11 years old. He made it to Fresno before he was picked up by local authorities and sent back home, but from then on the rebel child was often truant. Petty crime followed. Merle was in and out of juvenile detention centers, escaping numerous times, only to be thrown back in. The restless spirit that had stirred in the boy while watching those trains pass by his boxcar home would turn up in his music in songs like “Rambling Fever” and the hobo anthem “I Take a Lot of Pride in What I Am.”

Writing bad checks and stealing cars caught up with him in 1957, and he was arrested for burglary. At 20, Merle Haggard was in San Quentin. As he told the story later, another prisoner nicknamed “Rabbit” planned an escape attempt but advised Merle, who was playing in a country band in the prison, not to take part, as he had a future with his music. Rabbit killed a state trooper in the escape attempt and wound up on death row, an incident that surfaced later in “Sing Me Back Home.”

Merle later sang of his own rebellion and regret in “Mama Tried”:

One and only rebel child from a family meek and mild

My mama seemed to know what lay in store

Spite of all my Sunday learning, toward the bad I kept on turning

Till Mama couldn’t hold me any more

And I turned 21 in prison doing life without parole

No one could steer me right, but Mama tried, Mama tried

Mama tried to raise me better, but her pleading I denied

That leaves only me to blame ’cause Mama tried

A stint in solitary confinement and a 1958 San Quentin performance by Johnny Cash helped turn Merle’s life around. It was Cash who would later persuade Merle to “own up to” his prison term and write about it. In 2004, looking back on his penitentiary time, Merle said going to prison can “make you worse,” or “it can make you understand and appreciate freedom. I learned to appreciate freedom when I didn’t have any.” Merle decided that he wasn’t going to be an outlaw: “I’m one guy the prison system straightened out,” he said.

Paroled in 1960, Merle went back to Bakersfield, performed in local night clubs, and joined Wynn Stewart’s band as a bassist before forming his own band. Buck Owens was one of the pioneers of the “Bakersfield sound,” and Merle Haggard and the Strangers did their part to put that sound on the map, twangy electric and steel guitars helping to define music influenced by Jimmie Rodgers, Lefty Frizzell, Bob Wills, Chuck Berry, and Elvis Presley. From the mid-1960’s until well into the 80’s, Merle Haggard was one of popular music’s biggest stars, with 38 of his singles reaching No. 1 on the Billboard Country chart. In all, he released 71 top-ten country hits, 34 in a row between 1967 and 1977. A number were crossover hits as well.

Country songwriter Harlan Howard once said that Merle’s life’s work was making music for people who had “dirt under their fingernails,” and songs like “Working Man Blues,” “Hungry Eyes,” and “If We Make It Through December” celebrated the pride of working people, the hardships of Depression-era work camps, and the lives and troubles of working-class Americans as few others did or could. Merle scored some of his biggest hits with Vietnam War era songs like “Okie From Muskogee” and “The Fighting Side of Me,” his music giving voice to a “silent majority” disoriented by the revolution taking place around them. The songs—however light-hearted “Muskogee,” for instance, might have been intended—became rallying cries for a counter-counterculture:

If you’re running down my country man

You’re walking on the fighting side of me.

Merle, reflecting the attitudes of the white working class that produced him, didn’t much care for politics, and his own views could not be pigeonholed into neatly defined ideological categories. He distrusted corporations as much as he did government, was popular with rural and blue-collar Americans for blasting the hippies of the 60’s, but later on criticized Dubya and the Iraq war. He once said that “The little guy always gets screwed by the rich guy and the government.” “That,” continued Merle, “has always been the fight, and that always will be the fight.”

In “I’m a White Boy” (1977) Merle wrote from the perspective of a white working man disgusted by his society and his government, which had taken to pandering to blacks by promoting white guilt and the welfare state. With his characteristic irony, he says

Some folks call me a ramblin’ man

I do a lotta thumbin’ and kickin’ cans

And it wouldn’t do an ounce of good to call my name

’Cause Daddy’s name wasn’t Willy Woodrow

And I wasn’t born and raised in no ghetto

Just a white boy lookin’ for a place to do my thing. . . .

Yeah, I don’t want no handout livin’

And don’t want a part of anything they’re givin’

I’m proud and white

And I’ve got a song to sing.

Merle Haggard was an instinctive patriot, a man proud of his country, his people, and his background, his music rooted in the kind of attachments that make for a genuine patriotism, one not dependent on ideological nostrums. Merle would lament the decline we were all witnessing at the time in songs like “Big City,” “Rainbow Stew,” and “Are the Good Times Really Over for Good?”:

I wish a buck was still silver, it was back when the country was strong

Back before Elvis and before the Vietnam War came along

Before the Beatles and “Yesterday,” when a man could still work and still would

Is the best of the free life behind us now,

And are the good times really over for good?

One of Merle’s later songs, “America First,” reflected and summed up his common-sense patriotism:

Why don’t we liberate these United States

We’re the ones that need it worst . . .

Let’s get out of Iraq and get back on track

And let’s rebuild America first.

Merle Haggard’s life had some big ups and some big downs—he was married five times, fought off cocaine addiction in the 80’s, and mishandled his money, filing for bankruptcy in the 1990’s. He was in some ways a larger-than-life figure, in others a common man (though an uncommonly talented one), with all the frailties and shortcomings of the common people he came from. Merle was a lot like the people of my own extended family, people who went West looking for work during the Depression, sent their sons to fight (and sometimes die or return maimed) in America’s wars, people who were never wealthy and often dirt poor, yet a proud people, a people who unreflectively, instinctively loved their country, people whose patriotism and music reflected heartfelt attachments that were beyond rationalization or ideological formulas.

A true master—a musician, a painter, a writer—can take the material of life, the experiences of real people, their triumphs and tragedies, and make it into art. Merle Haggard was such a true master.

Merle Haggard was one of us.

Leave a Reply