Political language in America has assumed a maddening sameness, not to mention an overwrought self-righteousness, in this age of talk radio, blogs, and social media. Indeed, the editorials, tweets, press releases, and speeches of the two opposite camps—Team Red State and Team Blue State—often read or sound as if programmed by computer algorithm. But there is a crucial difference: Where the right’s memes are merely irritating, those of the left are laying the groundwork for national ruin. It is therefore the latter at whom indignation should be directed.

The lexicon of the left has reached new heights of cliché. With a shortage of imagination and an abundance of repetition, progressive activists have acquired a virtual patent on words such as “dignity,” “systemic,” “reckoning,” and “transformative,” as well as phrases such as “people of color,” “our democracy,” “national conversation,” and “marginalized communities.” If mainstream rightists had a genuine instinct for satire, they would have laughed this robotic, sentimental, authoritarian piffle off the national stage. But they don’t. And by default, they are enabling the left’s radical project of eviscerating America’s founding identity.

Two related words in the left’s radical glossary—“heal” and “healing”—are particularly intolerable because they disingenuously carry an olive branch. The tactic is a soft sell in the service of hard power. And it is proving indispensable to expanding the affirmative action principle to every aspect of our country’s life.

Al Sharpton, president of the Harlem-based National Action Network and street provocateur extraordinaire, has been at this for a long time. In his 2002 autobiography and campaign tract, Al on America, he wrote the following:

The first thing we need to do is acknowledge that you robbed me. Let’s start there with reparations. Let’s start with the fact that there is a debt owed. Then we can negotiate how we can repair it. What’s fair? We can start with creating an even playing field. But we can’t even get there until we recognize that there is a problem. We cannot bring up the discussion of how we will repair this, or what brings us up to par, because America still will not recognize officially or even unofficially that the dead are owed …America must admit its sins in Africa and its sins against people of African descent. It’s the first step toward healing.

One dreads the second and subsequent steps. Sharpton’s brand of “healing,” if instituted, would be a guarantee of endless racial strife.

And he has a lot of company nowadays. On January 18 of this year, the American Association of Colleges and Universities held its sixth annual National Day of Racial Healing, encouraging member institutions “to engage in activities, events, or strategies that promote healing and foster engagement around the issues of racism, bias, inequity, and injustice in our society.” The event—organized in conjunction with the W. K. Kellogg Foundation’s Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) campaign—is part of an effort to create “self-sustaining, community-integrated TRHT Campus Centers.”

The Kellogg Foundation also has contributed generously to the Center on Community Philanthropy, an affiliate of the University of Arkansas’ Clinton School of Public Service. In August 2021, the center launched the Racial Healing Certification Program, designed to “provide specialized training, education and unique experiences that promote skills development and competencies in the targeted area of racial healing.” The director of the center, Charlotte Williams, glowed: “This inaugural class comes from diverse backgrounds and experiences—and they are ready to take the next step in their commitment to understanding and promoting racial healing.” Somewhere Bill Clinton is smiling.

Another player in the healing industry is PACEs Connection, an organization geared mainly toward academicians eager to rescue people traumatized by recent events. The group describes itself as “an anti-racist organization committed to the pursuit of social justice.” Fittingly, on Jun. 2, 2020, a little over a week after the death of the sainted George Floyd, PACEs Connection held a webinar at which Carol Dolan, associate professor of community health sciences, declared,

At this moment in time, we all need to heal. So many people want the world to go back to normal, but we’re not taking the time to consider what wasn’t working with the old normal, and how we can do better.

Why is it that people who call for healing racial wounds tacitly support the very sorts of people who create those wounds? A concept long in use among sociologists, “vocabulary of motive,” may be useful in explaining this paradox. Briefly, vocabulary of motive refers to the ways in which a social group, whether formal or informal, reveals its character through ritualized language. Since words have symbolic as well as literal meanings, the group’s diction affects whether a particular person is accepted as a group member, given what the organization stands for. Prospective members must learn the “right” words to use. A particular set of words may be synonymous with the group’s language in denotative meaning yet at odds in connotation.

Political language follows this logic. “Freedom” and “liberty” are similar concepts yet often function as identifying terms for opposing groups. The left rallies around freedom; the right rallies around liberty. As another example, “disparities” is a preferred word among egalitarians, especially on race-related issues. For them, the denotatively similar word, “differences,” carries insufficient moral urgency. When a lawmaker, researcher, or clergyman denounces economic disparities, it is a sure sign this person believes that people who have “too much” wealth must surrender large portions of that wealth to those who have “too little.”

One begins to see why American political discourse has gotten so lazy and ugly as of late. More than ever, language is being incorporated into an arrangement of centrally managed tribalism. George Orwell witnessed its beginnings even before he wrote Nineteen Eighty-Four. In his 1946 essay, “Politics and the English Language,” he noted,

Modern writing at its worst does not consist in picking out words for the sake of their meaning and inventing images in order to make the meaning clearer. It consists of gumming together long strips of words which have already been set in order by someone else, and making the results presentable by sheer humbug.

The language of collective healing is humbug tailor-made for the overlapping worlds of mass therapy and mass bureaucracy. Far from objectively mediating and de-escalating social conflict—a laudable goal—this lexicon is a stalking horse for the multicultural left’s transformation of America into a model rainbow nation with socially equal outcomes. The word “healing” is designed to instill imagery of people united in trust, togetherness, and conciliation, but the underlying purpose is to discredit and punish political opponents. The ancestors of the healing project are many: Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, the late New York City Mayor David Dinkins’ characterization of his city as a “gorgeous mosaic,” and the late criminal Rodney King’s plaintive request, “Can we all get along?” Peace, love, and understanding never were this easy.

A growing number of Americans justifiably feel they’re being had. They sense that the language of healing serves as a moral pretext for street vagabonds to smash store windows, assault cops, and rip down public statues.

In the present context, the call for collective healing aims for one thing above all: to lull America’s white majority into abandoning its natural protective instincts, after which it will timidly defer to demands put forth by representatives of nonwhite minorities. The soft, hand-stroking feminine language, often amplified by calls for spiritual redemption, is crucial to consolidating power. Think of a velvet glove hiding an iron fist. The putative healers are the “glove,” brimming with moral conscience and facilitating the common good. They are quick to counsel the nation to drop its petty divisions, wipe away its tears, embrace racial diversity, and exchange hugs. They don’t tell you about the “fist” part.

But a growing number of Americans justifiably feel they’re being had. They sense that the language of healing serves as a moral pretext for street vagabonds to smash store windows, assault cops, and rip down public statues; and for lawyers, judges, politicians, and “civil rights” activists to create whole new categories of thought crimes. This is the natural turf of today’s ruling Democratic Party, which acts as both glove and fist.

On Jan. 12, 2021, during Donald Trump’s last days as president, Hillary Clinton exhorted conservatives and the rest of the Republican Party to “begin the healing and unifying process” by admitting that Joe Biden “was duly elected president in a free and fair election.” That there was likely little free or fair about the balloting and the vote count in several swing states was apparently not worth mentioning. In October 2020, Sen. Tim Kaine (D-Va.), who had been Hillary Clinton’s running mate four years earlier, gave a campaign boost to fellow Virginian and congressional candidate Cameron Webb, calling him “a healer in a nation that needs some healing.” Webb, who is black and a medical doctor, lost the general election but won a job in the Biden White House as senior policy advisor for COVID-19 equity.

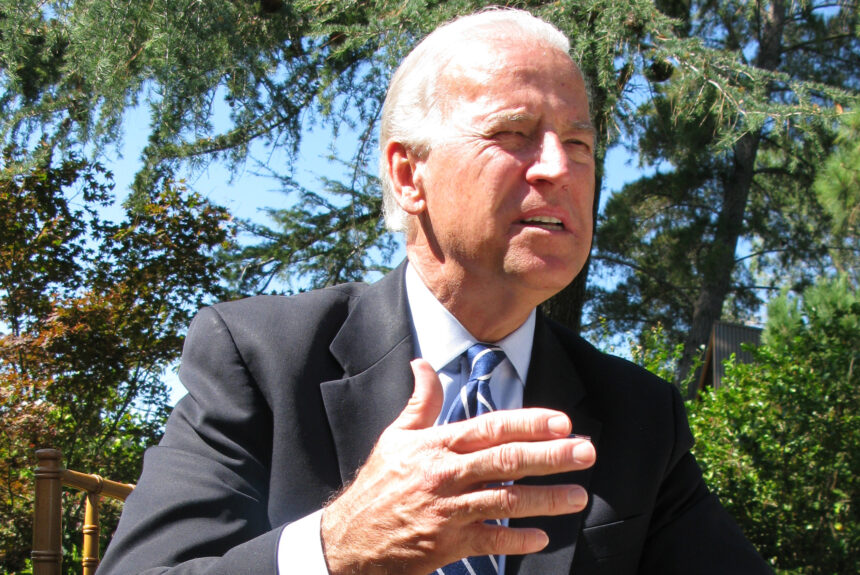

Speaking of the Biden administration, during a campaign stop in August 2020, future Vice President Kamala Harris called for slavery reparation payments to blacks on a vast scale. Such a measure, she said, would help blacks “heal” from “undiagnosed and untreated trauma” caused by America’s “dark history.” Candidate Joe Biden also got in on the act. In a prepared speech in early June 2020, a time when rioters were running wild, the future president stated this:

I look at the presidency as a very big job, and nobody will get it right every time, and I won’t either. But I promise you this: I won’t traffic in fear and division, I won’t fan the flames of hate. I will seek to heal the racial wounds that have long plagued this country—not use them for political gain.

Joe knew the drill. His political survival depended on it.

The escalating “healing” campaign springs from motives entirely unrelated to the rule of law or fair play. Unmasked, it is a rhetorical enforcer of a total program to shift money and power to nonwhites. Its deceptively empathetic language is intended to discourage actual debate in favor of a banal, stage-managed, Oprah Winfrey-style “conversation.”

National healing lingo is the language equivalent of the bliss-inducing soma opiate depicted in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World as having “all of the advantages of Christianity and alcohol; none of their defects.” Conjuring images of heaven on earth, talk of healing substitutes quasi-religious piety for statecraft, averting the hard work of assessing tradeoffs, limits, and worst-case scenarios. For the putative healers, their remedies are not to be assessed but instead uncritically accepted and affirmed. Nonbelievers must be gaslighted into reimagining their own defeat as a victory for the entire nation. The healers view any opposition to their program as morally unacceptable.

The image of America healing together has an understandable, if superficial, appeal. Yes, our nation is divided. But when was it not? When have we not had rival factions aching to tear each other to pieces? Henry Adams observed a little over a century ago in his autobiography, The Education of Henry Adams: “Politics, as a practice, whatever its professions, had always been the systematic organization of hatreds.”

James Madison made the same point in Federalist No. 10. He understood that our new republic was inherently unstable and required mechanisms to prevent any one faction from lording it over rival factions. But by making the forced economic redistribution from whites to blacks a nonnegotiable demand, today’s social pathologists have shown little or no use for the wisdom of the founding fathers.

Viewed from afar, the healing metaphor appears to be a humble, earnest effort to apply balm to the wounds of factionalism. But up close, under the guise of soothing racial wounds, the modus operandi of this egalitarian pacification program is to humiliate those who allegedly create or ignore those wounds.

If we are truly interested in the health of this nation and its people, then the campaign to heal America must be delegitimized. The language programming must be resisted. Until that happens, we are left only with wounds rather than healing.

Top image: Joe Biden speaks to supporters at a fundraising event in Atherton, Calif., in 2008

(Steve Jurvetson / Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Leave a Reply