A recurrent theme in Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States (1980) is how the prospect of a coalition between poor blacks and poor whites has often struck fear in the hearts of the wealthy classes in American history. Not surprisingly, Zinn longed for the emergence of an interracial coalition that, in his view, would bring about a more humane and just America for all. As a traditional Marxist, he equated injustice with class oppression and justice with socialism.

Such an interracial coalition had emerged for a short time in conjunction with the populist movement of the late 19th century. Today, we may be witnessing the emergence of another such alliance—ironically, perhaps, on the populist right—in part because the left has largely abandoned Marxist concerns with class struggle.

In a chapter on the prevalence of racism in pre-revolutionary America, Zinn writes:

Only one fear was greater than the fear of black rebellion in the new American colonies. That was the fear that discontented whites would join black slaves to overthrow the existing order. In the early years of slavery, especially before racism as a way of thinking was firmly ingrained, while white indentured servants were often treated as badly as black slaves, there was a possibility of cooperation.

Zinn adds that plutocratic interests had a stake in pitting these poor groups against each other by encouraging “the temptation of superior status for whites,” as well as enshrining “legal and social punishment of black and white collaboration.” Despite these measures, the primal fear of an alliance only intensified in the antebellum South. “It was the potential combination of poor whites and blacks that caused the most fear among the wealthy white planters,” he wrote.

Although the Civil War ended slavery, it did not end the oppression of blacks in the South, nor did Zinn believe it improved the lives of northern whites who “were not economically favored” any more than those of most Southern whites who “were poor farmers, not decisionmakers.” According to Zinn, the Civil War was a clash between “elites”—Northern industrialists versus Southern planters—not “of peoples.” He believed that various divide-and-conquer strategies in postbellum America have worked to distract poor blacks and whites from uniting against a common enemy that exploits both groups to this day.

The first edition of A People’s History appeared at a time when leftists often still desired the unification of all poor Americans against the class system. In the decades since, many prominent leftists have rejected this traditional vision of an interracial class-based alliance as the wrong kind of unity to build. Instead, they insist that the focus on class obscured the need to zero in on white supremacy as the real dragon to be slain. This shift from class to race has led to some curious results that should interest observers on the left and the right.

One of these results is the growing suspicion among leftists that Marxism is a species of white supremacy, precisely because it devotes more attention to class than to race. To be sure, Marx did privilege the importance of class oppression over racism, even going so far as to compare the hostility between exploited English and Irish workers in England with the hatred that poor whites and emancipated slaves felt towards each other in America. Although this analogy does not sound like an endorsement of white racial superiority, the Caribbean professor of philosophy Charles W. Mills, in his work From Class to Race: Essays in White Marxism and Black Radicalism (2003), urges readers of Marx and Engels to read racial prejudice between the lines:

…[A]t best there was no perception on their part that the peculiar situation of people of color required any conceptual modifications of their theory. And if we are less charitable, we must ask whether their contemptuous attitude toward people of color does not raise the question whether they too, like the leading liberal theorists cited above, should not be indicted for racism…

Mills coined the term “White Marxism” in order to highlight what he took to be the racist blind spot of subordinating racial injustice to the “white” preoccupation with class. Nor is he the only leftist to equate a focus on class injustice with white racism. George Ciccariello-Maher, in his book Decolonizing Dialectics (2017) also attacks the Marxian version of “dialectics” for exhibiting Eurocentric tendencies that, at best, ignore colonial oppression of nonwhite races and, at worst, condone them.

Ciccariello-Maher is not exactly famous for sympathizing with the plight of the white working class. He is, however, infamous for tweeting “All I want for Christmas is white genocide” on Christmas Eve 2016. In a subsequent tweet, Ciccariello-Maher attributed the 2017 mass shooting in Las Vegas to both “Trumpism” and the entitled mentality of whites. “White people and men are told that they are entitled to everything,” he wrote. “This is what happens when they don’t get what they want.” These tweets and others led to his resignation as a professor of political science at Drexel University, which condemned his tweets. Ciccariello-Maher said he resigned because he no longer felt it was “safe” for him to work there, due to alleged death threats.

above: cover of Robin DiAngelo’s 2018 book White Fragility (Beacon Press)

The most famous example of the leftist shift from class to race in recent years is, of course, Robin DiAngelo’s bestseller White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People to Talk About Racism (2018). This work has inspired politicians, celebrities, and other wealthy individuals to take up the cause of fighting “systemic racism” wherever it lurks, so long as it doesn’t affect their pocketbooks. Like Mills and Ciccariello-Maher, DiAngelo shows little interest in understanding or appreciating the impact of class-based injustices on white people. In a 2011 essay on white fragility that became the template for her book, she consigns the issue of class to this footnote:

Although white racial insulation is somewhat mediated by social class (with poor and working-class urban whites being generally less racially insulated than suburban or rural whites), the larger social environment insulates and protects whites as a group through institutions, cultural representations, media, school textbooks, movies, advertising, and dominant discourses.

Contained within this wordy example of academic prose is this message: Poor whites, despite their lesser degree of “insulation,” are complicit in maintaining an order that legitimizes white supremacy. Additionally, they benefit from this regime. (The fact that DiAngelo has become very wealthy as a result of her work on white fragility may explain why she is reluctant to treat social class inequalities as a serious subject.)

Is it any surprise, then, that some leftists were horrified when some nonwhite Americans joined with working class whites in voting for Donald Trump? The fact that the ex-president won a significant number of votes from black and Hispanic Americans in the 2020 election has set off alarm bells. Some pundits on the left reacted by warning of “multiracial whiteness.” This is the deplorable condition of embracing “white” ideas that tolerate the oppression of nonwhites. As Chronicles Editor Paul Gottfried explains in his article, “‘Multiracial Whiteness’ is the Latest Leftist Branding Iron” (American Greatness, Jan. 26, 2021), the solution to this false consciousness afflicting minority groups is clear: “[T]he disease of ‘whiteness’ has befallen nonwhites as well as biological whites, and we would do well to reeducate these bigoted nonwhites, particularly the ones who wore MAGA hats and voted for Trump.”

Needless to say, the kind of interracial unity Zinn hoped for is not the one that led minority voters to vote for the plutocrat Trump. Yet it is also unlikely that he would have welcomed the subordination of class to race that is so widespread on the left today; more plausibly, he would have regarded this strategy as an example of leftists acting as “useful idiots” in another divide-and-conquer strategy cooked up by capitalist elites.

From a right-wing perspective, the left’s division over race is all very good news. As long as the post-Marxist left ignores the reality of class discrimination, its parties will continue to bleed working class voters to the right.

Image Credit:

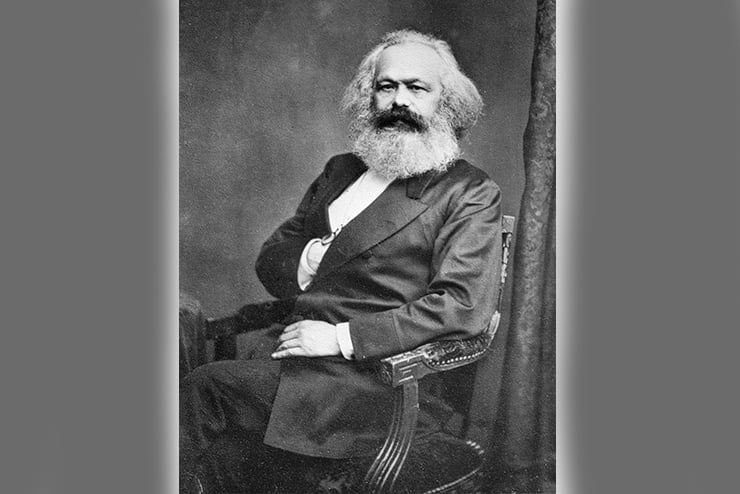

above: portrait of Karl Marx by John Jabez Edwin Mayal (public domain)

Leave a Reply