During Joe Biden’s 2020 campaign for president, when his fortunes were at their nadir, Joe Biden promised that he would nominate the first black woman to the United States Supreme Court. He reportedly made this pledge to James Clyburn (D-S.C.), the powerful African-American congressman, in return for Clyburn’s help in securing the black vote in South Carolina. That won the South Carolina primary for Biden and set him on the path to the nomination. Biden has reiterated that he intends to carry through on his pledge.

Fewer than 3 percent of American lawyers are black women, and while there is actually no requirement that a Supreme Court justice be a lawyer, that credential is a commonly understood minimal qualification. What this means is that President Biden’s pledge eliminated from consideration the 97 percent of American lawyers who happen not to be black females.

This was a blatant act of racial bias, which, as some commentators observed, violates federal statutory and constitutional provisions that forbid all racial and sexual discrimination in hiring as well as all imposition of racial quotas for federally funded institutions. These violations did not appear to trouble Biden, and the chances of any victim of such discrimination successfully securing relief from the federal courts is presumably nonexistent.

An ABC News/Ipsos poll revealed that only 23 percent of Americans want Biden to carry through with his promise, while 76 percent want “all possible nominees” to be considered. It is difficult to fault Josh Hammer’s observation, made on the American Greatness online magazine: “There is only one way to describe crass identity politics operationalized at this high a political level: Evil.”

Nevertheless, any academic who raises the possible impropriety (let alone the blatant illegality) of Biden’s plan is subject to immediate excoriation, as happened, for example, to Ilya Shapiro, a noted libertarian constitutional theorist, who had been slated to assume the directorship of Georgetown University’s Center for the Constitution. Shapiro tweeted that the “objectively best pick” for the Supreme Court vacancy would be Sri Srinivasan, a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, which is one of the usual feeder courts for Supreme Court justices. Srinivasan, Shapiro pointed out, is a “solid prog[ressive] & v[ery] smart.” Continuing an elliptical tweet, he noted that Srinivasan has the “identity politics benefit of being first Asian (Indian) American. But alas doesn’t fit into latest intersectionality hierarchy so we’ll get lesser black woman.”

This last observation of Shapiro’s triggered a firestorm, particularly upsetting Georgetown’s black law students, who demanded Shapiro’s immediate dismissal. Georgetown Law School’s dean, William Treanor, put Shapiro on administrative leave, barring him from the campus until it could be determined whether he had violated any of the school’s policies related to professional conduct, discrimination, harrassment, diversity, inclusion, and the like. Treanor seemed already to have reached a conclusion about the ongoing investigation when he stated that “Ilya Shapiro’s tweets are antithetical to the work that we do here every day to build inclusion, belonging, and respect for diversity.” Obviously Treanor and the protesting students perceived Shapiro to be making some kind of racist remark about the qualifications of black women for judicial service.

Presumably what Shapiro was actually seeking to point out is that there are qualifications other than race and gender that are more important in picking personnel for the nation’s highest bench. Some have defended Shapiro’s remarks on the grounds of academic freedom. His critics are not mollified, however, and while he has not yet been permanently sacked, one wonders how friendly an environment Shapiro will face if he stays at Georgetown.

President Biden has not yet announced his pick for the vacancy, although likely choices are three black female Court of Appeals judges, two of whom graduated from Ivy League law schools and served as clerks to Supreme Court Justices, which is perhaps the highest honor a young American lawyer can achieve.

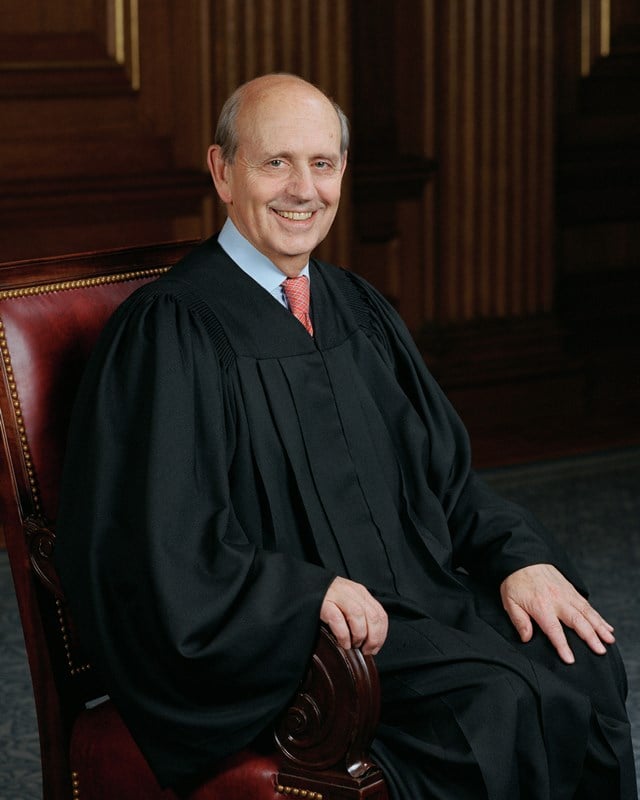

If any of these three is nominated, she would probably not decide constitutional cases in a manner significantly different from that of Justice Stephen Breyer, who announced in late January his plan to retire. However, as the 83-year-old liberal justice has been one of the Court’s most learned of judges, it would be a tall order for her (or any other nominee) immediately to match Breyer’s skills. Scholarly skills, though, are obviously not the point, as the Shapiro brouhaha demonstrated. Rather, what appears to be taking place is a longstanding struggle over which of two theories of constitutional interpretation ought to be appropriate for the court.

Image: U.S. Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer (Steve Petteway / Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States)

The older of these theories, limned in the 78th essay of The Federalist Papers, written by Alexander Hamilton, is that it is the job of the justices neutrally and sagaciously to discern the original understanding of the Constitution and its amendments, because that original understanding was the expression of the will of the American people themselves. Hamilton understood judicial review of federal and state laws for their conformity with the Constitution as the ultimate enforcement of popular sovereignty. Thus he could argue that when justices tested the acts of the executive or legislative branches against constitutional provisions, the justices were merely exercising “judgment” and not “will.”

Some of our greatest constitutional theorists are or were of this originalist view: Antonin Scalia, Clarence Thomas, and Raoul Berger come immediately to mind. But most constitutional law professors, and now virtually all the members of the Democratic Party, dissent from originalism. They adhere to a second theory: for them, as it was for Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Constitution is a “living document.” They believe it is the job of the Supreme Court justices to alter the meaning of the Constitution so as to conform to the changing standards of equity, decency, and inclusion (among other mutating progressive values) as the nation matures. This was certainly the judicial philosophy of Stephen Breyer as expressed in his major work, Active Liberty: Interpreting our Democratic Constitution (2005). Biden chimed in on the side of Breyer and his party when he declared on Feb. 1 that the U.S. Constitution is “always evolving slightly in terms of additional rights or curtailing rights.”

The idea of a “living” or “evolving” Constitution implies that justices are, when all is said and done, legislators—whose task is to make new constitutional law—and it is no surprise that anyone holding to that view would see justices as “representatives” of the people, like other members of legislative bodies. This can be carried to ludicrous lengths, as it was, for example, in 1970, when an undistinguished Republican senator from Nebraska, Roman Hruska, defended Richard Nixon’s ultimately unsuccessful nomination of G. Harrold Carswell against the charge that Carswell was, at best, a mediocre jurist. Hruska stated, “Even if he were mediocre, there are a lot of mediocre judges and people and lawyers. They are entitled to a little representation, aren’t they, and a little chance?”

“Representation,” in other words, trumps objective merit, and little better was Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer’s dubious defense of Biden’s intentions. “Under President Biden and this Senate majority,” the New York Democrat said, “we’re taking historic steps to make the courts look more like the country they serve by confirming highly qualified, diverse nominees.” The astute and provocative attorney and commentator Heather Mac Donald underscored how questionable “diversity” is as a metric to apply to Court justices. Writing in City Journal, she noted that the Biden administration announced in February 2021 that it would forego the normal vetting process of the American Bar Association because that process is “incompatible with ‘diversification of the judiciary.’” Mac Donald went on to write, “The quality of our jurisprudence matters. The race, sex, and ‘gender identity’ of judges do not.”

Scalia and Thomas would certainly agree with Mac Donald’s traditionalist notions, but Sen. Schumer clearly does not. Indeed, it was Schumer who, when confronted with the possibility of George W. Bush packing the bench with judges committed to “original understanding,” concocted an ingenious counterstrategy. During a period of the Bush presidency when the Democrats controlled the Senate, Schumer convened hearings in June of 2001 on what he called “judicial ideology,” arguing that it was necessary to strike a balance between “living constitutionalism” and “original understanding” so that neither of the two ideologies would become dominant. Thus, Schumer maintained, if Bush nominees simply replicated the ideology of the majority already on the bench, there ought to be a presumption against those nominees.

“Balance” has an attractive Aristotelian aura about it, but some of us argued at Schumer’s hearings that this was like seeking a “balance” between good and evil, since “originalism” was the only theory of judicial review consistent with popular sovereignty, and thus with our republican form of government. Indeed, ideology should not drive judicial rulings; objective fidelity to the law and Constitution should, and adherence to “original understanding” seems the only philosophy of judicial review that actually constrains judges. Since at least 2001, the divisions between the parties have become more sharply defined, with the Democrats’ nominees favoring judicial discretion to implement progressive ideals and with the Republicans’ nominees adhering to originalism. If originalism ever really triumphs, of course, there will be several revisions of long-standing questionable Supreme Court precedents, particularly in the areas of race, religion, and abortion.

President Biden’s nominee, whoever she turns out to be, will probably not have much of an effect on this debate, as the Court will still have a majority of six Republican-appointed justices and only three Democrat appointees. Curiously, however, a third judicial ideology, if one can call it that, has emerged in the last few years, exemplified most clearly in the jurisprudence of the Chief Justice, John Roberts. It has been labelled “institutionalism” or “judicial minimalism,” and its rarely acknowledged premise seems to be that the Court should do everything in its power to appear above partisan politics and therefore should avoid, where possible, politically controversial rulings. A guiding principle of that view is that the Court should take care, lest the more political branches seek to weaken it, as for example, by increasing the number of justices, to “pack the court.”

Roberts’s institutionalist perspective leads him, where he can, to follow previous constitutional precedent and to avoid interpretations that would undo politically popular, even if constitutionally-suspect, rulings and legislation. The most notorious such behavior on the Chief’s part was his decision in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (2012) to uphold the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”) on the dubious grounds that it was a valid exercise of Congress’s taxing power, even though its proponents had denied that the “individual mandate” in question was a tax, and even though Chief Justice Roberts conceded that Obamacare exceeded Congress’s powers to regulate interstate commerce.

Roberts is also famous for his position implicitly denying the reality of the now-clear party split on nomination philosophies, and for his condemnation of former President Trump for asserting that there were “Obama” judges and “Bush” judges and “Trump” judges. Justice Brett Kavanaugh has shown signs of following the chief justice as an “institutionalist,” and it is probably that tendency, rather than whoever Biden appoints to fill the Breyer vacancy, that should most concern those who still hope for the Court to revisit its many mistakes over the last 50 years, starting with Roe v. Wade.

In the next year, the Court will have opportunities to rule that there is no constitutional protection for abortion, that affirmative action to favor particular races in college admissions is impermissible, and that prior decisions have improperly driven religion from the public square. All of these rulings would be quite consistent with the original understanding of the Constitution, even though they might subject the justices to political attack. So be it. There is an ancient maxim, rarely invoked these days, but still compelling: Fiat justitia, ruat caelum. “Let justice be done though the heavens fall.”

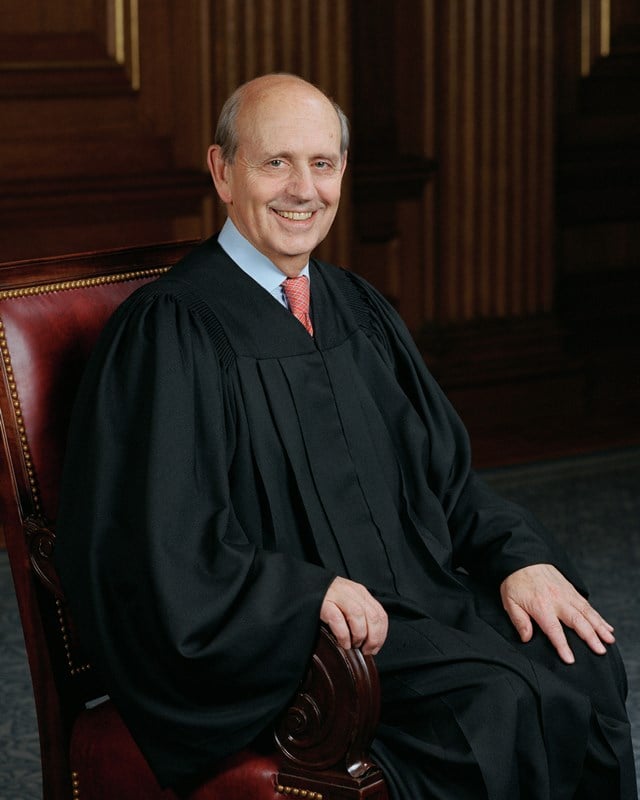

West facade of the United States Supreme Court Building in Washington, D.C. (Joe Ravi / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Leave a Reply