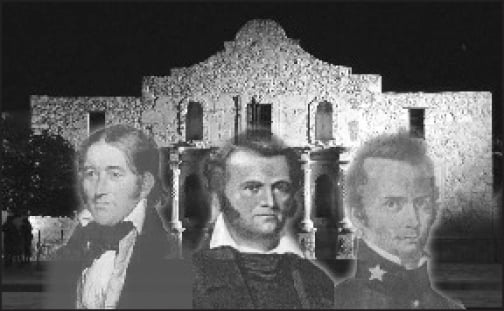

The names are legendary; the tales of heroism, a part of our heritage as Texans and Americans. Houston, Crockett, Bowie, Travis: All, save William Barret Travis, were nationally known figures before they came to Texas, which was then considered Mexican territory. Sam Houston had been governor of Tennessee, a protégé of Andrew Jackson, a war hero, and a potential presidential candidate. David Crockett had been a congressman, a popular hero, and perhaps America’s first media celebrity. James Bowie’s reputation as a fighting man spread his fame on the violent frontier.

But like the much-younger Travis, Houston, Crockett, and Bowie came to Texas to make a fresh start, to realize big dreams, to become the men they wanted to be. And all came initially as failures, each with a sense of a destiny that had gone unfulfilled.

They were not alone. Texas has long been a place that generates myths. From the very beginning of America’s engagement with Texas, the land itself sparked the American imagination. “Texas fever” swept through America in the 1820’s and 1830’s, as empresarios such as Stephen F. Austin opened Texas to American settlement. Americans headed for the border, scrawling “G.T.T.” on the doors of their abandoned cabins. They were “Gone To Texas,” gone to settle a new land and make a new life. Settler Micajah Autry, for instance, would write to his wife Martha, “I am determined to provide for you a home or perish.”

As Walter Lord wrote, the land that met the settlers was an

eye-opening, a breath-taking sight. . . . the sheer abundance of everything staggered the imagination. No drought or falling water table had yet taken its toll. The prairie was an endless sea of waving grass and wild flowers . . . The fresh green river bottoms were thick with bee trees, all dripping honey. Deep, limpid pools lay covered with lilies. The streams were full of fish, and game was everywhere . . . there for the taking. . . . It was enough to give birth to a Texas penchant for superlatives that was destined to endure. Travelers described sugar cane that grew twenty-five feet high in a single season . . . [and] pumpkins as large as a man could lift.

The Texas legend and the Texas identity, as so often happens, were forged in the age-old pattern of migration and war. Micajah Autry did make that home in Texas but perished securing it at the Alamo in a struggle that laid the foundation of a distinct Texan identity. Texas became the Lone Star of the West, an independent republic founded by heroes, storytellers, and rogues; forged by courage, determination, folly, and tragedy; defined by the tall tale and the tall men who made them. Texas became a maker of men and heroes.

Sam Houston was one of the fathers of the Lone Star Republic, leaving behind a life among the Cherokee, an apparently ruined political career, and a reputation as a warrior, boozer, and brawler. His first marriage ended in scandal, Houston’s young wife having left her husband after only 11 weeks. Houston never revealed the source of the conflict but departed Tennessee and the governor’s post—as well as a fair prospect of becoming a presidential candidate—to live among the Cherokee before leaving for Texas.

The rest, as they say, is history. Sam Houston won independence for Texas and a place in the Texas pantheon of heroes. At San Jacinto, Houston was wounded and had his horse, Saracen, shot out from under him. Twice the president of the Republic of Texas, a congressman, governor, senator, and revered hero, Houston was surely one of the most remarkable men in a remarkable American Golden Age. Before the Battle of San Jacinto, one of the pivotal clashes in American history, Houston told his troops to “Be men! Be free men, that your children may bless their father’s name.” On his deathbed, “Texas” was among the last words he uttered before passing into eternity.

David Crockett, who preferred not to be called “Davy,” had also left behind a political career when he came to Texas. Crockett the politician had mastered the style of the frontier tall tale, creating his mythical alter ego “Davy” as a larger-than-life figure in a tradition that produced Paul Bunyan, Mike Fink, Pecos Bill, and the protagonists of many a dime novel. Davy Crockett could grin a bear to death or ride a cyclone. The tall-tale tradition suited Crockett, who found his political support as a congressman among the hunter/squatters of West Tennessee.

A principled, if somewhat naive, man, Crockett broke with Andrew Jackson’s political machine and soon found himself out of a job, in debt, and looking for new prospects. So Crockett was soon “Gone To Texas,” leaving behind his family and the promise of a political career that was not to be. He asked his family not to worry: “I’m with my friends,” he wrote.

Crockett volunteered to defend the Alamo as a “high private.” His fiddle, courage, and good humor rallied the weary defenders. It is interesting to speculate what would have become of the Crockett legend had he not gone to Texas. Perhaps the popular hero of Jacksonian America would be largely forgotten if not for his death at the Alamo. Without Crockett’s decision to serve on the walls of the old mission, there would likely have been no “Davy” for the 20th and 21st centuries.

James Bowie also succeeded in creating a legend for himself. Having failed to secure the fortune and status as a man of property that he seems desperately to have wanted, he became involved in land-grant forgery schemes that damaged his reputation. In Texas, Bowie lost his beloved wife and family to a cholera epidemic, adding tragedy to his lack of financial security. Bowie was an adventurer and a man of action who saw Texas as one more chance to secure his desired station in life. His decision to stay at the Alamo assured him his place in history, securing for him a status in death that had eluded him in life.

Bowie’s connection to the Alamo legend ensured that his memory would not fade away. As a frontier brawler, then hero of the Texas War for Independence, Bowie provided a prototype for the gunfighter legends that would follow as the six-gun replaced the bowie knife as the weapon of the frontier duelist. And the Bowie of frontier legend was not all that different from the James Bowie of life: “fearless, quick to fight, yet a defender of the weak.”

William Barret Travis, who became commander of the Alamo garrison when Bowie fell ill during the siege, was, like Bowie, a complex figure. A young man in his mid-20’s at the time of the Texas Revolution, he did not enjoy the fame, political connections, or winning personality of Bowie, Houston, and Crockett. Texas streets and counties bear his name, but it is safe to say that he is the least-remembered, and least-beloved, of the Alamo heroes. Yet the Texas Revolution was the key to the making of both Travis the man and Travis the hero.

The road to a new life in Texas and immortality at the Alamo had not been a straight one for young Travis. A few years before, he had left Alabama a failure. Travis fled mounting debts, a failing marriage, and the collapse of his plans to become a respected man of influence. He had abandoned his wife and children, making a pledge to return once he had made his fortune in Texas (a pledge he never honored). Travis had the impulsive quality of a bright man with prospects who lacked sufficient maturity and judgment to see those prospects realized. He was brusque and prickly, not a man most people readily took a liking to. Yet he could be kind, even charitable, was religious, if not especially pious, and, as William C. Davis, author of a triple biography of Travis, Bowie, and Crockett, wrote, “More than once he sat up through the night with a sick and dying friend.”

Travis was born in 1809. Within a few years, his family had moved to the frontier territory of Alabama. Young Travis’s father saw to it that William would be equipped to better himself. He attended schools where he was tutored in Greek, Latin, French, rhetoric, history, and mathematics, finishing his formal schooling at 18, when he left home to read law in Claiborne, Alabama.

In Travis’s 1828 marriage to 16-year-old Rosanna Cato, we see another side of his character. A severe young man, so conscious of proper behavior and dress, Travis had a streak of the adventurer in him, a taste for chance, women, and horses—and he saw himself as a man of destiny, even beginning an autobiography as a 20-something immigrant to Texas. Though polished (by frontier standards) and a bit priggish, Travis was also impulsive: He liked to gamble and was equipped with a robust libido that sometimes got him into trouble.

Travis’s marriage to Rosanna was apparently a stormy one, probably hurried along by a pregnancy. They would eventually have a daughter and a son. Travis was busy, publishing a newspaper and studying law, as well as holding a commission in the local militia. Lacking maturity and judgment, he soon found himself drowning in a sea of debt.

Rosanna was apparently a harsh spouse, and she might even have sought comfort in the arms of another man—or Travis, at least, may have thought so. After being sued over his debts and following the eruption of a full-blown “feud,” as he called it, with Rosanna, Travis headed for Texas. Depressed and disappointed in himself, his marriage, and his career, he wanted a fresh start.

In 1831, however, Travis was not yet a complete man. A sense of responsibility would gradually develop in the young lawyer who became a leading member of the so-called War Party, which saw Mexican leader Santa Ana for what he was: no federalist who would support Texas autonomy, as many had initially believed, but a centralist dictator.

By 1835, Travis was a prosperous and respected lawyer and community leader. His prospects for advancement appeared limitless. After a relatively amicable parting with Rosanna (time having apparently healed some of the wounds both had acquired in their unhappy marriage), he brought his son, Charles, to stay with him in Texas. Travis began planning for the future, courting Rebecca Cummings in order to give Charles a secure home. The Texas Revolution intervened, however.

It is a measure of Travis’s growing maturity that so young a man could hold together the Alamo garrison and organize the mission/fortress’s defenses in the fateful month of February 1836. T.R. Fehrenbach, a native son who has captured the spirit of the early Texans far better than any other, has written that the revolutionary firebrand “was one of those most fortunate of men,” for, “on the grim stone walls of the Alamo,” “Buck” Travis had “found his time and place.”

Inside the Alamo, Travis was thinking of his son as his appointment with destiny approached. “Take care of my little boy,” he wrote to his friend David Ayers, who was looking after Charles. “If the country should be saved, I may make him a splendid fortune; but if the country should be lost and I should perish, he will have nothing but the proud recollection that he is the son of a man who died for his country.”

In a letter to his friend Jesse Grimes, Travis stated, in the words of historian Walter Lord, “why he was making his stand.” Travis remained at the Alamo for reasons of strategy, because of a bond among the defenders, and because of a “fierce desire to defend the new homes that dotted the land.” There was something else, however: Lord sensed in Travis the conviction that “a man should be willing to make any sacrifice” to hold on to his “liberty, freedom, and independence.” With these things, a man had “everything[;] . . . without them, nothing.”

Texas meant liberty, independence, and a fresh start for the men who were made legends there. We have those legends left to inspire us today, but, as I write these words, I feel a pang of sorrow. How will our sons become men in the bureaucratized, risk-averse, feminist post-America our elites envision for us? Fathers seeking a way out of the postmodern trap could do much worse than looking back to the time of frontier America, when Americans followed a Lone Star that made boys into men, and men into legends.

Leave a Reply