I went into the 2000 presidential campaign an enthusiastic supporter of Pat Buchanan’s bid for the White House as a third-party candidate. I emerged more convinced than ever that Buchanan would have made an outstanding president but skeptical that a serious right-wing party will be able to emerge, at least in the short run.

I knew that no major national party had emerged since the Republican Party was formed in the 1850’s, helped along by the implosion of the Whig Party and the increasingly sharp divide between North and South. I knew, too, that the most successful of all third-party candidacies, Teddy Roosevelt’s in 1912, accomplished little beyond the election of Woodrow Wilson.

There were more recent precedents, however, showing how third parties could effectively shift the national debate. George Wallace’s 1968 campaign sounded the death knell for the great New Deal coalition that had dominated American politics since 1932. Wallace’s campaign pushed the GOP to the right on social and cultural issues and laid the groundwork for millions of Southerners and ethnic Catholics to join Reagan and the Republicans in 1980. Ross Perot’s 1992 bid forced both the Republicans and the Democrats to make at least an effort to address ballooning deficits and burgeoning debt, helping make the 1990’s a time of comparative fiscal restraint in Washington. In fact, if Perot had not temporarily withdrawn from the 1992 race and if he had never begun talking about Republican dirty tricksters plotting to ruin his daughter’s wedding, he may very well have won: Most Americans had soured on Bush the Elder and were wary of Clinton, who was better known for the many scandalous rumors (most of them true) swirling around him than whatever he may have accomplished as governor of Arkansas.

I knew, too, that the major argument offered against conservative third parties by Republican propagandists—that the worst Republican candidate for president would always be better than the Democrat—was both unconvincing and, taken to its logical conclusion, a guarantor of the continued incremental leftward drift of American politics. The flaw in this argument can be seen by examining a favorite specter raised by those making it, that of a Democratic president being able to nominate new justices to the Supreme Court. Although we are always told that the Supreme Court hangs in the balance, this is seldom the case. Republican commentators poured forth column after column in 2000, warning that Al Gore would get to pick three Supreme Court justices if he were elected. In point of fact, he would have been able to appoint zero. None of the current justices seems particularly eager to leave, and the only events that will reliably create a vacancy—death or disabling illness—are beyond the control of even Karl Rove.

More to the point, justices appointed by Republican presidents have repeatedly been responsible for the decisions that have caused the most distress to conservatives, beginning with Eisenhower appointee Earl Warren. The two decisions of most concern to the GOP’s conservative base were both written by Republican justices: Roe v. Wade was authored by Nixon appointee Harry Blackmun; and Lawrence and Garner v. Texas, which struck down all statutes against sodomy, was penned by Reagan appointee Anthony Kennedy. (Ironically, a Democratic appointee, Byron White, both dissented in Roe and wrote Bowers v. Hardwick, the opinion overturned by Lawrence.) So many liberal justices have been appointed by so many Republican presidents that conservatives who insist that Bush will appoint only conservatives to the high court sound like nothing so much as a battered woman insisting that, “this time,” her drunken, abusive boyfriend will act differently. After all, a Machiavellian Republican strategist might not want the Supreme Court to overturn Roe v. Wade, which would both risk the wrath of voters who want abortion to remain legal (a group that includes many major GOP donors and such figures as President Bush’s mother and wife) and perhaps allow some pro-life voters to declare “Mission Accomplished” and return to their ancestral home in the Democratic Party.

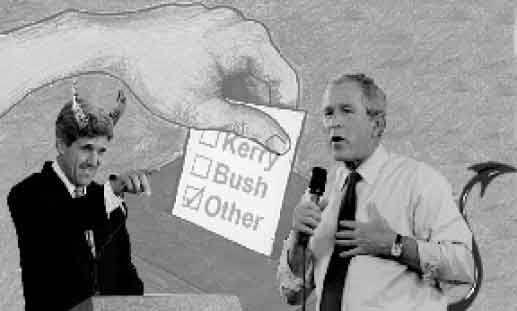

Taken to its logical conclusion, the Republicans’ standard argument against third parties also paves the way for a continued, incremental movement to the left in American politics. If conservatives should vote for George W. Bush because he is better than John Kerry, shouldn’t they also support Rudy Giuliani for president? Only when Republicans are made to realize that they cannot take conservatives for granted will Republicans regularly begin giving conservatives anything more than occasional rhetoric.

Unfortunately, my experience with Buchanan’s Reform Party candidacy—while not vindicating Republican arguments—fell far short of my hopes. I underestimated the many practical challenges facing third parties. I was not aware of the often fractious and occasionally unstable nature of some of the people attracted to third-party efforts. Above all, I mistakenly believed that most Americans were interested in having presidential candidates willing and able to conduct a serious debate on the major issues facing the country. These factors doomed Buchanan’s candidacy, and they threaten to doom any attempt to create a serious conservative third party in the foreseeable future.

Ballot access is a daunting challenge for a third-party candidate, consuming a large amount of his scarce resources: Third-party candidates need to be familiar with the election laws of all 50 states, and campaigns need to allocate many volunteers to gather the necessary petitions, pay professionals to do it, or both. Furthermore, they must deal with the open hostility of the two major parties. For a time, virtually all of Buchanan’s national campaign staff disappeared in 2000, because they were all in North Carolina gathering signatures to get Buchanan on the ballot. Even though he had greater resources than other third-party candidates, Buchanan was unable to get on the ballot in all 50 states. The GOP kept him off the ballot in Michigan, just as the Democrats are trying to keep Nader off the ballot in such places as Oregon and Pennsylvania this year.

Getting media access is also a challenge. Media coverage is geared toward the horse-race aspects of campaigning, which means little attention is given third-party candidates, even those who regularly provide good copy, such as Buchanan. In 2000, both Buchanan and Nader were shut out of the debates, even though there is little doubt that they would have enlivened them and forced Bush and Gore to confront issues of great concern to many Americans, including the impact of globalization.

Globalization is also directly related to another daunting obstacle—money. In 1996, Buchanan was able to finance a credible run for the GOP nomination by raising small amounts from many individual donors, mostly through direct-mail solicitations. This is how conservative candidates have raised money since the early 1970’s. Buchanan enjoyed the support of only one Fortune 500 CEO. By contrast, in 2000, George W. Bush almost wrapped up the GOP nomination before the first primary vote was cast by raising an unprecedented amount of money from many large donors throughout the country. Estimates of the total cost of this year’s campaign near one billion dollars. Any candidate skeptical of globalization (as any conservative third-party challenger likely would be) simply cannot compete in the money race with candidates enjoying ready access to corporate donors, which means that such candidates will find it increasingly difficult to compete in the primaries and almost impossible to run a third-party campaign.

Another obstacle facing third-party candidates can be the nature of some of the people drawn to third parties. Both the Republican and Democratic parties tend to be relatively cohesive because those running the parties are motivated primarily by the prospect of enjoying monetary gain from holding office, lobbying those who hold office, and cashing in on connections made while holding office. Few congressmen ever return to gainful employment (or even go home) after reaching Washington. By contrast, third parties are often fractious, as shown by three of the third parties that competed in 2000: The Reform Party has split into two parties, the America First Party and the Reform Party; Nader has run away from the party that supported him last time, the Green Party; and the Natural Law Party, which attracted Reform Party members who opposed Buchanan’s nomination, has simply disappeared.

Such infighting takes a toll. There is little doubt that Buchanan’s campaign was badly hurt by the protracted battle for the Reform Party nomination and the well-publicized walkout of malcontents from the party’s Long Beach convention. In my experience, those who bitterly fought Buchanan were motivated not by ideology (which can be a cohesive force) but by personality: Fighting was what they enjoyed doing. Indeed, Buchanan’s opponents gravitated toward the unlikely (and gravity-defying) figure of John Hagelin, an instructor in physics at a school established by the Transcendental Meditation movement in Iowa. Hagelin, like other TM adherents, believes in “yogic flying,” which so far consists of crossing one’s legs and bouncing but is said to offer the possibility of effortless flight through the air.

The greatest obstacle facing a serious third-party effort on the right is not the suprarational beliefs of the likes of John Hagelin but the suprarational nature of politics today. Our politics are at once acrimonious and meaningless. The acrimony is obvious to anyone who spends five minutes watching cable TV. The meaninglessness is shown by the nature of the debate between the major candidates. They are in substantial agreement on such major issues as globalization, immigration, trade, the need for an interventionist foreign policy, and the need to continue expanding the federal government, differing largely on how best to tinker with the tax code. They do not even have any fundamental disagreements over Iraq: Kerry voted for the war and has said he would cast his vote the same way today, even after we found no weapons of mass destruction in Iraq and no link between Saddam Hussein and Al Qaeda. Can any debate be more meaningless than the one we have seen so far this year, with the liveliest discussion focusing on what John Kerry did or did not do in Vietnam 35 years ago?

At least since the beginning of the Clinton presidency, American conservatism has been characterized less and less by an interest in ideas and policies and more and more by intellectually disabling cults of personality—first, the negative cult of personality surrounding Bill Clinton; now, the more conventional one surrounding George W. Bush. The left is following suit, as many Democrats now feel about Bush the way many Republicans feel about Clinton. For each side, there is far more passion generated by the real or imagined misdeeds of the other candidate than by the policies advocated by their own candidate.

Presidential politics have become so bitter because the major differences between the candidates are now cultural, not ideological; many voters now treat the presidential campaign not merely as one front in the Culture War but as the only front. This is dangerous for conservatives because the White House has not been the instrument of the left’s victories in the Culture War, and merely having a Republican in the White House will do little to alter the outcome of that struggle, especially when the President is committed to nothing more rigorous than “compassionate conservatism.” As long as conservatives view voting for president as a way of registering which side they are on rather than as a way of advancing a meaningful agenda, there is little chance of building a credible third party focused on promoting conservative issues.

Leave a Reply