Peter: “Lord, wither goest thou?”

Christ: “I go to Rome to be crucified.”

The monastic choir stalls of the Church of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Florence were occupied not by the hermit-monks of the Camaldolese Order to whom they belonged but by laymen, members of the Platonic Academy. From the lectern, the Latin periods being intoned were not from Leo, Gregory, Augustine, or Jerome, but from a new translation of Plotinus. The one presiding by the altar was not a prior but a philosopher, Marsilio Ficino, founder of the Academy, translator of the works of Plato and of his Alexandrian alter ego. We would not know of the replacement of the nine psalms of Matins with the Enneads on a morning in early fall 1487 if it were not for the existence of a letter of outraged protest from the prior general of the Camaldolese Benedictines to the prior of the church where the uncanonical choral solenne tornata accademica was held. Yet even if the letter had been lost, the long view of subsequent history would perhaps have justified a suspicion that such things had occurred. Indeed, three centuries later, these strange, proto-masonic matins were to have an echo in another church dedicated under the name Mother of the Savior when the Goddess of Reason was enthroned before the chancel of Notre Dame in Paris in November 1793, to the strains of Chenier’s hymn to Liberty. Perhaps they will have another still, if we can trust the prophetic vision and clerical realism of Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson in his turn-of-the-20th-century Lord of the World:

A great murmur of enthusiasm had rolled round the Abbey from end to end as the gorgeous curtains ran back, and the huge masculine figure, majestic and overwhelming, coloured with exquisite art, had stood out above the blaze of candles against the tall screen that shrouded the shrine . . . As the chink of the censer-chains had sounded in the stillness, with one consent the enormous crowd had fallen on its knees . . . England had found its worship once more—the necessary culmination of unimpeded subjectivity . . . In cathedral after cathedral had been the same scenes . . . Telegraphic reports had streamed into the London papers that everywhere the new movement had been received with acclamation, and that human instincts had found adequate expression at last . . . Life was the one fount and centre of it all, clad in the robes of ancient worship . . . It was positivism of a kind, Catholicism without Christianity, Humanity worship without its inadequacy. It was not man that was worshipped but the Idea of man, deprived of his supernatural principle.

From Ficino through Spinoza, the Lodge, and Feuerbach, to the mass demonstrations of the 20th century, and to Heaven- or Hell-knows-what in the 21st, from philosophy through polity to mass marketing, there is an unequivocal coherence of object: the emancipation in Christendom’s Old and New Worlds of human reason, of the social order, and of individual pleasures from the service of the God of the Bible. The paraliturgical expressions of this emancipation may be zany or short-lived, like Lodge rituals, Brasil’s Comptean Positivist Temple, or the Nuremberg rallies, but what they signify is deadly serious and both ideologically and temporally secular.

And it all began in Florence. Now, bashing the forces unleashed on the world by the Renaissance might seem as crazy as questioning the value of the Enlightenment or ungratefully rejecting the benefits bestowed on humanity by Stalin’s winning of World War II. Nonetheless, I will manfully gird myself up to undertake the first of these three. As for the second, I hope it will simply be a Q.E.D. by the time I have finished. As for the third, in no way would I blame Uncle Joe for successively hoodwinking, first, the Nazis and, then, Yankee ex-Puritan capitalists who, for the moment at least, are enjoying the most recent, if not the last, laugh. In any case, they are all on the same side, at least from the eschatological perspective: the left. Asides aside, allow me to explain.

The genius of Christian Romanitas, both Constantinian and Carolingian, Byzantine and Frankish, was to blend the empire of Greek wisdom and Latin order with the concrete, barbarian vigor of Semite, Syrian, Slav, Armenian, Angle, Copt, Celt, German, and Magyar. This Roman power of cultural assimilation and sublimation was not the result of the merely material advantage offered to conquering legions or invading tribes, but of the religion that both emperors professed. This unified the imperial and barbarian worlds and made them one single thing: Christendom, Christianitas in both East and West. This Roman, Christian oikoumene, long beset by schism and diminished by jihad, made a final formal attempt at reasserting itself at the Council of Florence in 1439. It was the failure of the project of this synod, more than anything else, that allowed the Renaissance to become what it was and so led to the cultural devastation we see all around us.

From the middle of the 14th century, the Orthodox of the Eastern Roman Empire had translated, studied, and admired the best products of the Latin Christian mind. The ardently Orthodox monk-emperor John-Joasaph Kantakuzenos commissioned the translation of Aquinas and Augustine into Greek. The decidedly antipapal Makarios Makres, Joseph Bryennios, and Mark of Ephesus were nonetheless students of the Angelic Doctor and his synthesis. They were, like the Thomists in the West, heirs of the great Patristic tradition that maintained the Church’s biblical rule of faith and expounded it with the organon of reasoned argument and the ordering power of metaphysical intuitions borrowed from Plato and Aristotle via Dionysius the Areopagite. Additionally, they possessed the uninterrupted patrimony of classical rhetorical paideia. They were, in short, well prepared to engage in theological dialectic with their serious Latin counterparts in order to overcome the schism, reunite Christendom, and, thus, provide a bulwark against its enemies without.

On both sides, however, other forces were at work. The Greek periti lodged in Florence at the very same Camaldolese priory of Santa Maria degli Angeli that, in a few decades, would become the scene of the weird rite described above. At that time, it was the home of a great monk and man of letters, Blessed Ambrose Traversari. While there, the Greeks received abundant invitations, not so much to speak of theology as to enlighten the circle of Cosimo de Medici about Hellenic learning and, most particularly, Platonic philosophy. There were among the Greeks and the Latins those who admired the other side for reasons having nothing to do with the dogmas discussed at the council: Greeks who admired the diversity and progressive tendencies of late Scholasticism and the relative intellectual freedom of the Western schools, Latins who hoped to find in the Greeks the uncorrupted literary and philosophical culture of pagan humanism. These two parties found each other, and soon the neopagan Platonist crank Gemistos Plethon was delivering lectures on Plato to the circle from which Ficino’s Academy would spring, and his students, the future cardinals Bessarion and Isidore, were planning new careers as Westernized Greek humanists and papal legates.

Meanwhile, the pars sanior produced the acts of the council. The friars and the Greek episcopal monastics slugged out its definitions. But who could blame the latter for being suspicious of those other Latins who seemed to be moving from late-Scholastic diversity into neopagan syncretism? When they got home, the union was already a dead letter, and the rest is history. What a disaster for the West! The Orthodox, whose coherent spiritual and liturgical traditions and whose finely honed sense of doctrinal probity could have bolstered the forces of their Catholic counterparts, left their lesser spirits, opportunistic humanists, behind in Italy and shut themselves up on Mt. Athos and in the monasteries of Constantinople, content to anathematize both humanist and mendicant friar alike. The union of Eastern and Western Romania was destroyed, perhaps, politically by the Turks but spiritually by the Florentine humanists and Greek zealots.

In Italy, the Roman Christian intellectual order in place since the days of Severinus Boethius unraveled. His project, identical in substance to that of the Byzantine East, of the harmonious exposition of Christian mysteries with a single philosophical tradition encompassing both Plato and Aristotle, was replaced by a paganizing radicalization of the positions of both and the pitting of one against the other and all against the Faith. The Platonic Academy in Florence had its counterpart in the radical Aristotelians of Padua. When the next Church council, the Fifth Lateran, was held from 1512 to 1517, it resolved not the serious dogmatic differences of earnest Eastern and Western Roman Christians but a complex intrigue that pitted the Medici pope, manipulated by the Florentine Platonists, against the radical Aristotelians who were triste dictu defended by the Thomist Cardinal Cajetan. Things had come to such a pass that the teaching of the mortality of the soul and the eternity of the world in universities had to be forbidden, and clerical students had to be reminded that they must study theology, not merely philosophy and letters.

The disintegration of Christendom had begun under the aëgis of the revival of classical philosophy. The ascendancy of autonomous reason and anti-Christian ideology were guaranteed. It is not at all unreasonable to believe that these currents would have been greatly mitigated had the union of East and West been effective. The East would have vigorously confirmed the best of the medieval Latin tradition. Instead, the Latin West was now forced to ignore the East in its attempts to maintain Christendom, and, after the Reformation, it would openly compete with it, especially in Slavic lands. The humanist Pope Pius II was able to write to the Sultan Mehmet II, conqueror of Constantinople and amateur of Italian humanism, encouraging his study of Greek philosophy, assuring him that the doctrines of Plato and Aristotle were substantially those of the Christian faith, and urging him to convert to Catholicism, so that Pius might crown him Roman emperor.

The rigorist reaction of the saintly Savanarola and the anti-Roman animus of Luther were both tragically inefficacious in their opposition to the humanist onslaught. In the case of the latter, the Protestant movement further weakened the fabric of Roman Christendom with its rejection of the norm of the Imperial Church of the Fathers. The words of Article 19 of the 39 Articles of the Church of England exemplify the rejection by even the most moderate of Protestants of the living patristic norm affirmed at Florence: “As the Church of Jerusalem, Antioch, and Alexandria have erred so also the Church of Rome hath erred, not only in their living and manner of Ceremonies, but also in matters of Faith.”

That the Renaissance humanist tradition represented by the Platonic Academy of Florence is at the root of modern revolution, especially in its esoteric elements, is not some extreme integralist accusation. It is the considered opinion of the best students of the movements of the quattrocento. The late Italian Renaissance scholar and Marxist Eugenio Garin, among others, can be consulted on this point in all serenity. What is not sufficiently understood, however, is the extent to which the continuation of the schism between Old and New Rome made anti-Christian revolution a reality, and so helped to cause a Protestant reaction that might otherwise have been unnecessary.

By now, the Roman Christian composite of Greco-Roman and barbarian culture has been corrupted, and a Brave New World is being established in which an esoteric elite governs the white- and blue-collar proletarian membra disiecta of the old order. The world of late antiquity, with its capacity to transform those outside it into itself, born of the Christian faith, has been overcome by the disintegrating power of an enemy within the walls. We latter-day Christian Latins, unlike our Trojan forbears, were undone by Greeks who went home: Timeo Danaos et dona auferentes. But perhaps from this disaster, now reaching its conclusion, a still newer Rome can be born. Pope John Paul II has had no more fervent desire than the reintegration of the Eastern and Western communions. There is no doubt that he regards this as a necessary condition for the new evangelization of the traditionally Christian lands of the Old and New World, a program he announced early in his reign at the shrine of Santiago Matamoros at Compostela. It is a cultural as well as a doctrinal imperative. Christendom, he says in his letter Orientale Lumen, must breathe “with both lungs.”

The great Hungarian Benedictine physicist Stanley Jaki, starting from a perspective different from my own, draws similar conclusions as mine and conveys them elegantly. In an article published in Theology Today in 1973, he wrote:

Ficino’s school of Neoplatonism in Florence around 1470, celebrated with Plato a natural or scientific knowledge of God which had no room for a revelation as understood in the Bible. In 1470 and afterwards, few were aware of this big difference between the proud a-priorism of Plato and the humbling story of the Bible. Worse even, some successors of Peter were more drawn to Plato than to the Bible. Councils were not effective in stemming the sad drift toward paganism. No wonder that embittered and frustrated Reformers took into their own hands, for better or for worse, the cause of reform, that is, the reassertion of the biblical knowledge of God over the natural knowledge of God. For the ultimate spiritual issue in the Reformation concerned not particular doctrinal points, but the reassertion of the Bible and the Cross over Plato and nature. Two hundred years went by and reformers as well as counter-reformers should have seen at long last that their real challenge was not with one another. The Encyclopedists, a motley lot, were at one in rejecting everything supernatural . . . There is now in the making an attack on Christ and Christianity, an attack more sweeping and thorough than any other before. As was the case with the members of the early church we shall not be attacked on the particulars of our dogmatics . . . The world is ready to tolerate our skirmishes on finer points of doctrine. The world might look even benignly on our liturgical practices because man, so the wisdom of the world has it, should project himself in symbolic rituals. But the world will not be impressed by the efforts of latter-day Christian Neoplatonists who are, in order to gain the world, busy recasting the Christian message in the subtle inconsistencies of process theology and evolutionarism.

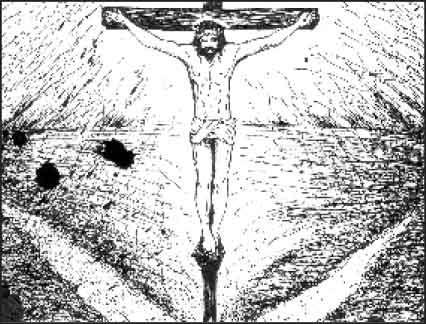

Father Jaki makes a key point: The world tends to take Christian liturgical worship lightly, not opposing it with the vigor with which it would attack us for our moral teaching. Here is precisely where Eastern Christendom has so much at heart and so much to offer, which perhaps will be the source of a renewal of Romanitas. It is worship, after all, which is the heart of Christian culture, since it is the act of the God-Man Himself hanging on the wood of the Cross and lifted up from our altars: “And if I be lifted up from the earth, I will draw all men to myself.” Christians are called to imitate what they handle in their liturgy, and this means ultimately to meet the world’s false cult of reason and self-will with the witness of martyrdom. Is this not the truest second birth and initiation, truer by far than any elitist “renaissance” with its bogus esoteric mysteries? In the same article, Father Jaki goes on to say: “The church, as the Fathers liked to point out, was born on the cross from the pierced heart of the Son of God. Our unity will not be reborn except through our readiness to be crucified with Him.”

One of the anaphoras of the Roman Missal praises the Father in the fulfillment of Malachai’s prophecy: From age to age you gather a people to yourself, so that from the rising of the sun to its setting a pure oblation may be offered to Your Name. May today’s Christian Romans of East and West say, with Christ, Urbi et Orbi—“I go to Rome to be crucified.”

Leave a Reply