In 1976, the Episcopal Church, U.S.A., met in General Convention to consider, among other things, two questions: the adoption of a new Book of Common Prayer and the ordination of women. Whether they knew it or not, the delegates were actually resolving a deeper, more disturbing dilemma: whether to remain orthodox or to remain respectable.

From its beginnings and well into the 20th century, the Episcopal Church had enjoyed the luxury of being both. While theological debates raged in other branches of Christendom, Episcopalians agreed on the tenets of the historical creeds and quarreled instead over high church and low church. Though, in some locales, other denominations brought social status to their membership, nationwide, the Episcopal Church was the place to be if you wanted to join the country club or meet the president of the bank. At St. Albans, orthodoxy and respectability were old friends and sat in the same pew on Sunday mornings.

Then, in the second half of the 20th century, a rift occurred; and, soon enough, the two were no longer speaking. The nation suddenly found itself in the grip of social revolution. The civil-rights movement, peace movement, women’s movement, and sexual revolution quickly changed America from a stable, traditional society into a political and cultural war zone. The media and the academy quickly sided with the revolutionaries and began to exert an ever-increasing influence on Christian churches. Soon, it became unfashionable to adhere to creeds and traditional ways. The chic, educated crowd was ready for new ideas, new social arrangements, a new church.

Episcopalians were told that the Book of Common Prayer—dating back to the 16th century—was too penitential, too focused on sin. When praying, people knelt like cowering serfs instead of standing straight and tall. They repeated phrases like “have mercy upon us, miserable offenders” and “there is no health in us.” Even worse, the Episcopal Church had an all-male clergy in an emerging era of militant feminism. If a woman could be the CEO of a Fortune 500 company, she should be able to be a priest or a bishop in the Episcopal Church.

Indeed, elite Episcopalians concluded that, if they did not slough off their gauche orthodoxies and enter the Age of Aquarius, the Church would no longer be a fashionable place to promenade on Sunday mornings. At the beginning of the cultural revolution, the leading spokesman for such heterodoxy was the Rt. Rev. James Pike, who became a celebrity clergyman while serving as dean of New York’s Cathedral of St. John the Divine—the most conspicuous pulpit the Episcopal Church had to offer. And, as far as the mainstream media were concerned, he was saying all the right things: He rejected the Virgin Birth; he dismissed the doctrine of the Trinity as false and irrelevant; and he endorsed the ordination of women. An accomplished phrase maker, he called for “more belief and fewer beliefs.” He was “refreshing,” “outspoken,” “brilliant.” His thoughtful face appeared on the cover of Time.

This notoriety won him the see of California and the growing disapproval of his orthodox fellow bishops, already a shrinking number in the Episcopal Church. In 1966, a group led by Henry I. Louttit, bishop of the Central Archdeanery of South Florida, demanded that Pike be tried for heresy.

John Hines, presiding bishop of the Episcopal Church, met with Louttit and a small delegation in New York and told them he had polled key figures in the mass media, who had declared unanimously that a heresy trial would severely, disastrously damage the Church’s image.

Most of the bishops agreed. The bishop of New York expressed the feelings of the majority: “Of all the methods of dealing with Bishop Pike’s views, the very worst is surely a heresy trial! Whatever the result, the good name of the church will be greatly injured.”

Hines asked Louttit and his cohorts to allow an ad hoc committee to address the problem more informally, less visibly. Louttit reluctantly agreed. Members of the committee met, engaged in a great deal of hand wringing, and came back with a report that said (in part):

It is the opinion that this proposed trial would not solve the problem presented to the church by this minister, but in fact would be detrimental to the church’s mission and witness. This heresy trial would be widely viewed as a “throw back” to centuries when the law in church and state sought to repress and penalize unacceptable opinions. It would spread abroad a “repressive image” of the church and suggest to many that we were more concerned with traditional propositions about God than with the faith as the response of the whole man to God.

At Wheeling, West Virginia, the House of Bishops adopted this statement by an overwhelming vote, though they also agreed to “censure” Bishop Pike—a small, dry bone tossed to Christian orthodoxy. In the above passage, two phrases—“unacceptable opinions” and “repressive image”—revealed what was really going on.

In the first of these phrases, the bishops suggested that Pike’s dismissal of the Trinity was mere “opinion” rather than a denial of eternal truth. For decades, high and low churchmen had been arguing heatedly over the practice of garnishing the liturgy with sanctus bells and incense. Following this decree, they could also argue over the doctrine of the Trinity in the same earnest but harmless way.

In the second phrase, “image” is elevated to the level of First Principle. Once he had made short work of the Trinity, Bishop Pike refused to say “in the name of the Father, Son, and Holy Ghost” during services he conducted. Given the unique centrality of this doctrine to Christianity, what Pike professed was a modern version of the Arian heresy. Yet to say so officially, the bishops agreed, would be to expose the Episcopal Church to the charge of “dogmatism”—an unacceptable alternative to looking the other way.

The bishops came together in Wheeling as one kind of church and parted ways as quite another. Henceforth, the Episcopal Church would have no theology to anchor its speculations and enthusiasms, no commitment to immutable truths, no real mind—only a deepening concern for public opinion, which its defenders euphemistically called “tolerance.”

At the time of the Pike controversy, the Episcopal Church had no formal catechism. Its theology could be found in the text of the Book of Common Prayer (1928 version)—embedded in the Apostles’ and Nicene Creeds, in the Prayer of Consecration, and in services such as Baptism and Ordination. This theology was orthodox in every respect, which is why the modernist bishops and priests saw the Prayer Book as a dinosaur, at best, and a dire threat to “progressive thinking,” at worst. It had to go.

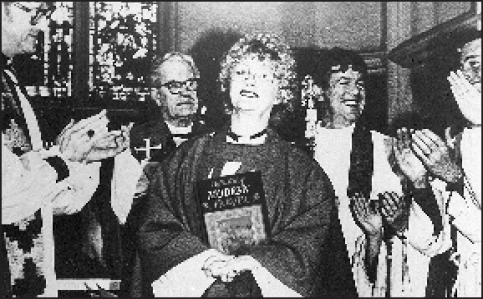

Even as the liturgical debate raged, a parallel controversy was developing—one that would again threaten the Church’s respectability. The feminist movement had captured the imagination of the media; and, suddenly, an all-male clergy was giving the Church “a repressive image.” A debate emerged; but even before the 1976 General Convention could resolve the issue officially, three retired bishops, acting in defiance of then-current canon law, ordained female priests. And why not? No compelling authority existed to restrain them. And hadn’t Bishop Pike received a mere slap on the wrist?

The orthodox forces had been too preoccupied with the Prayer Book to think seriously about the feminist movement. The General Convention—stacked with anti-Prayer Book activists—stunned the Church by canonizing the ordination of women.

Nor could this new church defend Christian moral teachings. A year after the ordination of women, Bishop Paul Moore of New York—a high-profile Pike-alike—ordained an open and practicing lesbian. A brief and fruitless furor ensued. Moore issued an “apology” of sorts, and the ordination of open homosexuals was put on the shelf for several decades.

This transformation from orthodoxy to theological anarchy by no means occurred without damaging consequences. Hoards have left the Episcopal Church. No one knows for sure how many or where they went, but, clearly, a substantial portion—wounded and disillusioned—sit at home on Sundays, watching Meet the Press. Others have “gone to Rome” or the Greek Orthodox Church. A few have even ended up in evangelical congregations—a far cry from the solemn liturgy they loved in the old Episcopal Church.

However, a significant number formed what are now called “continuing churches,” most of them using the 1928 Book of Common Prayer, with bishops and clergy who can trace their apostolic lineage back to one of the 12 Apostles. The growth of these churches has been slow and strife-ridden. When Moses led the saving remnant out of Egypt, he probably took with him a ragtag band of pagans, pickpockets, and murderers—anyone who wanted out of Egypt. Later, he took a branch, dipped it in the blood of a lamb, and sprinkled everybody, making them all Jews. When the 1976 General Convention ended, the best and the worst left the Episcopal Church together: the true believers who could no longer tolerate fashionable heresy and, with them, the ideologues, misfits, and power seekers.

A volatile mix of the orthodox and half-sane, these defectors have wandered in the wilderness for decades, bickering among themselves, splitting into even smaller fragments held together by certitude and memory. Indeed, to cynical observers, they have become what the Episcopal hierarchy predicted: excessively dogmatic and finally irrelevant.

However, at least one man believes that these disparate factions can find enough common ground to form a single unified church—Bishop Paul Hewett of the diocese of the Holy Cross. A trim, dark-haired man in his late 50’s—convivial, articulate, and often eloquent—he takes the orthodox position that the Christian Church exists in unity with Christ, no matter how often we carve up its temporal jurisdictions or deliver it for a time to heresy.

“The Church’s unity,” he says, “is the sign to shattered, splintered humanity of wholeness and new life in Christ. Our unity is a given. We cannot make the Church one. It already is one. What we do is reveal this unity, or obscure it.”

Bishop Hewett sees his first order of business as the melding of eight separate continuing churches into one organic whole—a free-standing and orthodox “province.” The chief obstacle to the unity of these communions is not really doctrinal, canonical, or liturgical. With some serious and self-effacing debate, a consensus might be reached on the ways and teachings of the Church. So what is the biggest stumbling block to unity?

Bishops.

Each branch of the continuing church has its geographical jurisdictions, and they tend to overlap. In one state, for example, two rival bishops reign in cathedrals a mere 30 miles apart. So which one, in the interest of reunion, would be willing to put his purple tunic in mothballs and surrender his crook and miter? The probable answer to that question is “neither”—as Bishop Hewett well knows. Thus, in his drawing-board province, all current bishops would retain their episcopal status, able to confirm laymen, ordain priests, and even participate in the consecration of new bishops.

However, it might be necessary to ask that some bishops allow other bishops to become head dog in these new geographical jurisdictions. As Bishop Hewett has said,

We recall the example of the Antiochian Orthodox Church, which at one time had two separate jurisdictions in the United States. They became a single jurisdiction when one of the bishops said to Metropolitan Philip, “You are a better man than I. So you look after the whole thing.” That kind of courage and humility is a miracle of God’s grace.

“Miracle” is the right word. Yet he counts on precisely that kind of grace to reconstitute at least a portion of the fragmented Anglican Communion in America. “The Holy Spirit,” he says, “is not very interested in our territorial squabbles.”

“If we can’t do this,” he told a reporter for the Philadelphia Inquirer, “then I think Anglicanism in this country is lost. Everyone who has left [the Episcopal Church] will either become Roman Catholic or Eastern Orthodox or go nowhere. We have one more five-year window if we’re going to put the thing together right.”

To this end, he is constantly on the road, talking to bishops in other communions, meeting with like-minded clergy and laity in Great Britain, even traveling to Norway and Sweden, where a chilly remnant is struggling to keep the flickering flame of orthodoxy alive. Fishing for true believers in Scandinavia may seem like trolling for marlin in a wading pond, yet the Swedes and Norwegians periodically come to London to join Hewett and others in strategy talks. So maybe the grace Bishop Hewett seeks is beginning to work its quiet magic in the most unlikely places.

As for the Episcopal Church, it is still on a collision course with historical Christianity. Its positions on women’s ordination and homosexual rights are irrevocable. If its bishops were to back down now and reaffirm traditionalist views on these subjects, they would lose the respectability they have so tenaciously retained over the last 30 years.

Bishop Pike’s spiritual heirs are everywhere; but, over the past decade, the most prominent has been the Rt. Rev. John Spong, bishop of Newark, now retired. Bishop Spong has discussed his militant unbelief in several books, including Why Christianity Must Change or Die, in which he argues, point by point, that all of the historical doctrines specified in the creeds are nonsense and that the Christian Church must reject them or shrivel to irrelevancy and be swept away by the winds of change. Bishop Spong is by no means as bright or as learned as Bishop Pike was; but, in an age when pagan ignorance is in fashion, he does not have to be.

Bishop Spong’s highly publicized sanctification of homosexuality helped to pave the way for the 2003 consecration of Bishop Gene Robinson, who, years earlier, had left his wife and children to live openly with a male lover. When the General Convention put its imprimatur on this rejection of biblical morality, the Episcopal Church found itself seriously at odds with worldwide Anglicanism. Indeed, Episcopalians may soon find themselves out of communion with Anglicans in other countries. Bishop Robinson did not help matters when, in a recent interview with Planned Parenthood, he trumpeted his own moral relativism. When asked if he was “pro-choice,” he answered: “Absolutely. The reason I love the Episcopal Church is that it actually trusts us to be adults. In a world where everyone tries to paint things as black or white, Episcopalians feel pretty comfortable in the gray areas.”

Indeed, they do. These days, that is the place to be, the most respectable part of town. The entire popular culture has moved into the gray house next door and throws block parties every weekend. The stern folks who live way over on Black-and-White Street—such as Bishop Paul Hewett and his followers—do not know what they are missing.

Leave a Reply