“It behoveth thee to be a fool for Christ.”

—Thomas à Kempis

Hawkins was doing his version of an Iranian student who had missed eight weeks of class, yet wanted an “A” in the calculus course.

“I know you are wondering why I have not to come to class since school start. I am good student. You can tell. But I am only support of my wife, my brother, my mother, and now my cousins from Iran. I must work all the time.”

“It must be hard. Maybe you ought to drop out. You’ve missed all the quizzes.”

“Oh, I can never do it. I must graduate in three years. Absolutely. I have had calculus in high school. It is very easy for me.”

“I understand. But you’ve never been to class and never taken any quiz. You’ve got an ‘F’ as of right now.”

“I was really hoping for an ‘A.'”

Hawkins’ Iranian accent was perfect and the people at the party howled in laughter. His face could change radically and with great rapidity. Orie moment he could be Mussolini, posturing before his troops, the next a ghetto kid playing basketball. He became these people. While he was an undergraduate he had done stand-up comedy in small nightclubs. After his own schooling was completed, he taught mathematics at the University of Houston, and now he was teaching math at the medical school.

He was envied and admired by the young, upwardly mobile professionals in his set in Houston. The surgeons made more money, but none of them seemed to have such a good time as Hawkins. Lately, he was envied even more because he had the freedom that followed the breakup of his marriage. No one said this, but the surgeons and lawyers still had to have their affairs on the run, in secret. Hawkins was having the time of his life right before their very eyes. Or so they thought. He still had his five-year-old 450 SL convertible. His former wife got the house, but he had moved into one of those opulent apartment complexes that try to simulate Caribbean resort hotels. A great plastic dome covered the pool and Jacuzzis, and the recreational area, the Pleasure Dome, looked like part of the Amazon rain forest airlifted in.

Yet with the jazzy apartment, sports car, and plenty of money from his job, Hawkins lived with a low-frequency anxiety just underneath all that he thought and did. He felt as if his life had no pattern, that it might have been assembled from different suppliers scattered around the country by someone who had never seen a, man before.

He left the party with his latest love, a chesty physical therapist who was into cats and computers. She was trying to work out the physics of a new routine to help a male patient stand more upright by lying on his back and doing some new exercises. She had come to Hawkins for help. He helped her into bed.

This night, after the usual frenzy, he lay awake while she dozed. Her giant, tail-less Manx cat sat on the nearby chest of drawers and stared at him. He looked as big as a bobcat. Staring. The hard eyes made Hawkins feel like the stranger he was in this bedroom. He finally dozed for a few minutes, only to be awakened by the cat when it lunged on the bed and began pawing Hawkins’ foot under the sheet. He kicked the cat off the bed and hurriedly put on his clothes, as he explained to the startled therapist that he needed to get home.

Three days later he came down with rheumatoid gonorrhea. His knees and elbows had swelled and he began to feel not very upwardly mobile. While he was undergoing treatment, he couldn’t drink, and he found himself loading up with ice cream at the nearby Baskin-Robbins. This led him to much solitary introspection. It was while browsing through the Praline-Pecan, the Mocha Chocolate, and the Paradise Pineapple that he ran into a quiet, brown-eyed woman who also lived in his complex. She lacked the glamorous look that would have made her a target of Hawkins. Now, given the judgment that had fallen upon him, given his dark remorse, he was not feeling so glamorous himself. Thus began his relationship with Monica.

Since sex was out of the question, Hawkins began for the first time to talk to a woman with no intention of seducing her. In the evenings after his classes at the medical school he would stroll over to her apartment, where she usually busied herself cooking an evening meal. By then she had slipped out of her secretary clothes and into jeans, looking like the East Texas farm girl she was. Her parents had urged her to learn typing, believing it would end up being worth more than the high school diploma, so maybe she wouldn’t have to stay on the farm. Frankly, she liked the farm, but her father felt this was a step up.

For Hawkins, who had grown up in Chicago, Monica was as exotic as a Guatemalan Indian. He kidded her ways and speech as she fixed them field peas and cornbread and on a weekend even her version of East Texas barbeque. The peas had come from her father’s garden. Hawkins would do his version of a hick farmer and Monica would smile and keep on cooking. It came to him that the plainness of the food and even the unadorned healthiness of Monica were just what drew him, what kept him there. She had a strong body and good legs which were more apparent when she was in her jeans. Around her small waist she wore a western belt with a large silver buckle. She carried herself with a vitality that was self-restrained, bounded. He carried the painful reminder of the women who hung out in all the clubs full of designer plants and designer pants. A darkness had, in fact, moved in even before the gonorrhea. He was not sure of the cause . . . maybe it was just leaving his wife. When he had found no one else who seemed to suit him, he fell into a state of drift. He drifted among a woman with a cat, a woman with a membership in a tennis club, and a medical student trying to improve her grade.

Late one evening as he sat at poolside, his feet dangling in the water, he heard, “OK, Hawkins, what’s this story I hear you’re hustling a Christer. I knew you were kinky, but this sounds like reverse kinky.”

His wise-cracking friend Barolo backstroked down the pool to where he sat. Barolo had had the typical reaction to Hawkins’ misfortune with the gonorrhea. He had laughed. Hawkins was irritated by this, but guessed he would have done the same, though if someone caught the flu nobody laughed in his face. He remembered that in the Army everyone howled when someone got the clap. Some applause! A scholar draftee volunteered that the word “clap” came from Old French, from brothel and venereal sore. Nowadays it looked like the whole city was a brothel.

Barolo heaved himself from the pool and as he sat next to Hawkins the water streamed down through the hair of his chest and legs. “So what’s this taking up with a fanatic?” he cackled.

“I don’t have anything else to do. Besides, she’s a nice girl. She plays the organ at church. When’s the last time you went out with a nice girl?”

“Ha. You’ll see to her corruption. Wait’ll the church elders get on to you. They’ll see you in the stocks and lashed till you bleed.”

“I met some of them once. They’re not so bad. Most of them are insurance salesmen or real estate brokers.”

“Right. A good place to make business contacts. So . . . you’ve even been hanging out at church.”

Just then the resident manager dimmed the lights in the Pleasure Dome. It was eleven o’clock. In the false twilight they continued to talk.

“Yeah, I’ve been visiting the natives. Monica invited me to go and I don’t mind. It’s like doing anthropology in some exotic place.”

“Watch out you don’t go native. It’s happened to some anthropologists. They start out with a kind of noblesse oblige and before you know it they’ve married the chief’s daughter or shaman’s son and they’re there for the duration. They’re as misguided as Rousseau, that oaf.”

Hawkins knew he could expect an edge on anything Barolo might say about Christians. For Barolo had been one. Born one, raised one. Then he turned away. Not forty-five degrees, but one hundred and eighty. Hawkins had nothing in his experience that was much like that. He grew up believing in baseball. His father had died when Hawkins was still in junior high and he had gone to church with his mother for the funeral. He had been into another church when he had gotten married. That was his wife’s idea. She didn’t go to church either, but she couldn’t have all the show, the bridesmaids, the reception—a real feed after the ceremony with caviar, champagne, and the works—without doing the whole thing. It was like getting in costume for a school play. He knew, though, that Barolo, as a matter of principle, wouldn’t walk into a church. Give him a few drinks and he could get fired up and rolling. At a party one night someone rattled his cage and he could be heard above everyone else: “Leap of faith, leap of faith. What they don’t tell you is you could just as easily land on Ra the Sun God or Quetzalcoatl! All they really mean is tyranny of the local. It’s like a Soviet election. One candidate.”

Hawkins smiled to himself as he thought of that evening, and he smiled outwardly now, glad to have this odd, witty companion in a town where he didn’t have many friends who could be witty or serious about anything except their latest tennis racquet, their newest restaurant find. What Hawkins found pleasing was the serious way he was funny, the serious world he was laughing about, his slanted wit slipping through the world in ways most people never imagine. While the jokes occasionally were tinged with a slight bitterness, it was from the kind of integrity one expected in mathematics, but was much harder to maintain in the world outside of numbers. The world of contingency outside of numbers was one where a husband and wife could betray each other, the domain of gonorrheas.

Somehow to become one with his friend’s mind, Hawkins began to talk in the accents of a Protestant TV preacher, as if he were offering a gift to Barolo for his company. “We are gathered together tooodaaay here in Gawwwd’s House to give thanks for living in this great country of ours. Let us remember our fighting men who guard our freeedooms as we approach this Easter season.” Soon Barolo was grinning, relishing a guy from Chicago who had the ear for East Texas or, better. Big Thicket Protestant.

“I got to watch you religious types,” he said. “You’ve commercialized Easter with chocolate rabbits and chicken eggs. Soon you’ll be turning to my one big American holdout. Thanksgiving. Porcelain gift turkeys that lay candy eggs or else eight red-nosed turkeys, ‘On Hobble, On Gobble,’ will be flying down my chimney demanding my damn credit card before they’ll leave anything.”

“Gawwwd giveth or taketh away, but no credit,” rejoined Hawkins.

One day late in February, a false spring day but full of promise, Monica invited Hawkins out to a Big Thicket dinner at the family farm. Her home was not some sprawling ranch house, but a clean, well-kept frame house with big porches front and back. The barns were close by, with an ample garden space, now mostly with the remains of winter vegetables like turnips and collards separating them from the house. His northern accent drove home that he was a stranger, but he was Monica’s friend and so he was taken right in by the weather-lined father and the tanned, plump mother, and by Monica’s two rough teenage brothers. Straightaway the brothers had him out at one of the barns looking at their cutting horses, both wearing hats as big as umbrellas, their jeans, belts, and boots following a dress code as rigid as a Marine guard’s.

At midday dinner the table top was jammed with food, with lots more on a sideboard. A big hen with cornbread dressing occupied the center, but fanned out below this mountain of glazed tawniness were great foothills of field peas, potato salad, a huge round of cornbread, flanked by a barbequed ham with links of pork sausage around it, a giant white boat of gravy, a hummock of rice and a quivering mound of cranberry jelly looking nervous before what was to come. Monica’s father asked God to bless all this opulence, thanking Him at the same time for their guest, and even though Hawkins felt self-conscious being singled out for God’s notice, he felt like he had been made welcome.

Halting long enough to give God his due, Monica’s rambunctious brothers put on an eating display that would have stirred the envy of the Aga Khan. Hawkins generally had salad at most for lunch and even before the apple pie and ice cream arrived he was reeling. Fortunately, nothing was expected of him after this ritual feast except to sip strong coffee in a rocking chair on the front porch while the brothers put on a riding display in the front yard. How they managed it so soon after dinner Hawkins could not imagine.

On the long drive back to Houston, facing a setting sun, he felt how important such gatherings had become, especially now. This family’s daughter had gone off to the jungle of Houston to make her solitary way, far from the vortex of the family, partly because her father felt she would be better off there. No doubt because he felt the labor wouldn’t be as hard. Hawkins wondered how good the trade had been, swapping harder work for the loneliness of the city. He felt that he was losing his trust in progress.

As he recalled the parting scene with Monica’s family in the yard, watching them leave for the city, it seemed like a classical frieze on some temple, or an old photograph from an earlier time in America—the weathered couple in plain dress, as if they had been together from the beginning of time, and offered to time to come their cowboy sons astride their mounts, ready to shoot it out with death if he dared to show his face. How had he, Hawkins, smart guy from Chicago, failed to figure out the right moves? He had been fast on his feet. What had been missing?

His Mercedes sports coupe swept into a darkening Houston. The outskirts were filled with drilling equipment sitting idle from an oil boom gone bust. Row upon row of thrown-up apartment complexes were vacant or abandoned. A dying city. Near the interstate highway, from the broken window of an abandoned house, a curtain blew outside as if to wave goodbye.

Monica’s church decided to put on a play, to be performed the week before Easter. At supper one evening she shyly asked him if he would be in it. Since there would be so many male parts, to start with 12 disciples plus Jesus, they were running short of grown men in their 20’s and 30’s. Hawkins was momentarily stopped, but after a minute he began to think what a funny idea that was, him playing one of the disciples.

The next evening the two of them went to the big room in the “education” center near the main church building, where there were many small classrooms and one central hall with a raised platform. When necessary, this could be turned into a makeshift stage, but the actual performance would be in the church auditorium.

After a little milling around, the youth director, a bald yet youngish-looking man, called out in a prissy way for them to gather round. “A good group, a good group. We’re going to have lots of fun and we’re going to put on a really good show.” He swelled with self-importance. One might have thought he was directing a Hollywood cast of thousands rather than the few who would carry out the intimate drama of the last night before the Crucifixion.

All but Hawkins were known to the director, although he had seen him once on an earlier Sunday when he had come with Monica. The roles of ten disciples were promptly handed out to the men best known to the director, and for the first time Hawkins learned that there were two Simons, Simon Peter and Simon the Zealot. Most of the others had not known it either. Hawkins discovered that there had been two Judases, too! And Judas, the son of James, was given to the other remaining actor.

“Oh, dear, I do hope you won’t mind playing Judas Iscariot,” fluttered the director, looking at Hawkins.

Monica laughed, uneasily. “I didn’t prepare him for something like this.”

“It’s OK, it’s OK. It’s only a play,” Hawkins said.

“Well, I guess that leaves me to play Jesus,” the director said, resigned. “So. A word about costumes. We won’t wear our modern clothes, but since we don’t have wigs available, we’ll just have to do without. Anyone wanting to grow a beard, or borrow one, that’s fine.” He handed out the typed scripts. “Let’s just run through it once tonight so you’ll know what to expect. You can learn your lines at home.”

Hawkins followed the plot with great interest. He knew generally how things went, but none of the specifics. Like the two Simons and the two Judases. The cast practiced breaking invisible bread and drinking invisible wine from a common cup. Hawkins thought he might have the best part. Simon Peter was a pretty good one, too.

Judas could have come straight out of a Chicago Mafia movie, Hawkins thought. He goes over to another family, the chief priests and scribes, and cuts a deal to set up his own godfather. They tell him when they want it: not on a holiday (bad press). Judas goes back to his own family and as he drinks wine with his godfather, the godfather looks him right in the eye and hints that he knows something is going down. One of the troubles Hawkins had staying in character was this prissy, balding Jesus.

Still, Hawkins was interested in his part. It always seemed like bad guys in the movies—in life for that matter—seemed to be more interesting. Like bad women. Hard to explain.

For the next week he thought a lot about Judas. Even though the little play had the same plot year after year with no revisions, he figured it was a good idea to read up on it. One of the confusing aspects of the story, and of the parts played by Judas and Peter, was Jesus telling them what they were going to do before they did it, kind of giving away the end. But then everybody knew the end of the play anyway. At first his notion was that knowing the end made it unrealistic. But as he pondered over this and Judas’ betrayal, it came to him that the plot of everybody’s life was rather similar if you took the high points: birth, growth, and death. Everyone knew the ending, just like Jesus’. It was just not knowing the timing. About all one could do was consider the style that would be his own. Judas no doubt considered himself a flexible kind of guy, one who could change grounds pretty quick, looking out for the main chance. It wasn’t like the town hadn’t thought he was doing a useful thing. He was going to get himself a little piece of land with the money, sort of God’s little acre, Hawkins laughed. Starting over.

Slowly Hawkins thought he was getting into Judas’ head. It took a lot of individuality to do what Judas did. Like some sort of Cold War spy who had to operate mostly alone, be his own man.

All went smoothly until the youth director ended up in the hospital. It was discovered he had a hole in his heart and would have to have an operation. Hawkins got this news from Monica one evening and she seemed much flustered about what would happen to the play. She talked to the minister and he said perhaps he could fill in with the directing chores, but that he didn’t feel he ought to be playing Jesus. It ought to be someone from the congregation. When Monica approached a fellow from the Young Adult Sunday School class, he said he didn’t want to play Jesus either, but he would play one of the disciples if they were hard pressed. Hawkins saw it coming, like a slow curve headed into the stands, then turning straight for home plate where he stood.

“Who? Me?”

“We’re really in a jam and I don’t know who else can save us.” Monica’s big brown Texas eyes pleaded with him.

When his friend Barolo dropped by again, he howled.

“I warned you about going native, didn’t I? I have to admit even I didn’t think you would go this far. This clap must have gone to your head.”

“I knew you’d take it well,” Hawkins grinned.

“I thought this was just a way to stay around your new chick, but I think you’re caught. Just think of all that good scientific education going down the tubes.”

“I’m just helping these people out. Maybe they recognize good acting talent.”

“Hollywood couldn’t get big name actors to play that spectacle about Jesus several years ago. Had to get an unknown. There’s a danger in starting at the top. Kind of hard for people to take an actor seriously playing one of the Three Stooges once they’ve seen him play God.”

“Only half God.”

“Listen to the new theologian. Tell me, old buddy, how do you square all this magic with yourself.”

“I’m just doing a little archaeology. Can’t hurt anything. Besides, I still get Monica,” he grinned, raising his eyebrows like Groucho Marx, and tapping his imaginary cigar.

“Just a little empirical reconnaissance, huh? Trying to get a little certainty, is that it? You’d be better off doing your science if certainty’s what you hunger for.”

“That’s getting to be a laugh and you know it. You should have learned from your boys Poincaré and Godel that science rests on assumptions like everything else. These assumptions are just convenient, just conventional. Of course, we can’t go around telling the uninitiated that. They’d find out what charlatans we are.”

“So you’re ready to substitute the blood of the Lamb for the axioms of mathematics, is that it? You’re a queer one, Hawkins.”

The closer Hawkins drew to the actual performance, the more the part of Jesus occupied his thoughts. He was not used to doing serious parts. Irony, cracking wise, impersonation had been his strong suit. Besides, he hadn’t had any professional training. In college he had practiced with a buddy for their comic routines. His timing was meshed with the other’s response. He could give tips to his partner and vice versa. A hand gesture, a drooping clown’s mouth of sadness, a double take. But here he was alone.

Part of Hawkins’ difficulty was getting into the head of his character. Judas had been a lot easier. He just put himself in the place of the Mafia stoolie and went from there. But how did you get into the head of God, or half-God, or whatever this mysterious combination was. Soon he was pouring over the conflicting accounts in the Gospels in the evening with Monica. Like many who had grown up in the church, Monica knew the general story, but she had a hard time answering the questions Hawkins was asking. For her, the story was not a mental problem, something to be taken apart and looked at in pieces. The story was as much a part of her as the sounds and smells of the church sanctuary, of Easter and Christmas. He was pursuing this like research at the medical school. He wanted specific details about background. Monica borrowed several biblical commentaries, and soon Hawkins was over his head in abstruse arguments about the text.

What did Judas actually do? Did he identify Jesus to the police or had he given the Sanhedrin inside dope about Jesus’ secret claim to be the Messiah? Was the Last Supper a day before Passover? Hawkins was swamped in minutiae. It happened that way in his school research sometimes. He had to back off and try to remember where he really wanted to go.

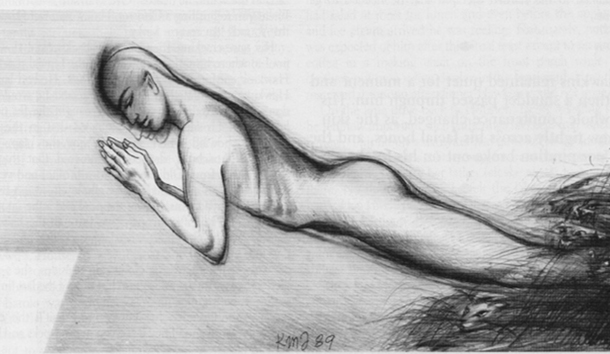

He focused on this group as oriental men who had been together through hard times and who were meeting to break bread in an upstairs room. This tight circle would break apart within hours. Hawkins tried to think of instances of betrayal in his own life. Like when his wife and he betrayed each other but nothing was said, nothing was acknowledged. Jesus knew that Judas was going to turn stoolie on him, and that his good friend Simon Peter would take a walk when they accused him of being a friend of Jesus’. Hawkins began practicing his face, a face that would carry all the sadness in his eyes.

Besides this Hawkins concentrated on the garden scene. During the day, Jesus had been preaching in town, but at the end of each day he liked to get away from the noise and crowds to a place on nearby Mount of Olives, a small garden called Gethsemane. After supper on this last night, he did the same, and it caught Hawkins’ attention that he anticipated what was going to happen back in town, that he was torn between what he might have to do, and the hope that there was some other way. That he was not sure. There was real anxiety here. Hawkins could get into that. Jesus dreaded going ahead, because he was not absolutely certain that this was what he needed to do.

Monica had in the meantime made her version of what a Palestinian would have worn during the time of the play. One evening she had asked Hawkins to let her pin the cut-out material on him in order to get the right fit. As she moved around him tucking here, pinning there, he began to be aroused as she touched him. He forced himself to think of something outside Monica’s room, which was becoming close, even warm. He focused on the red hibiscus he could see out Monica’s window that faced the gardens of the Pleasure Dome. With his attention on the red flower, he felt warmth move up from the base of his spine and travel to his neck, suffusing him alternately with small chills and a delicate feverishness. He needed to get back to his apartment.

Soon the week before Easter came. Hawkins was surprised how fully this play had taken over his time, how he now focused on this above all things day and night. When the disciples gathered for the dress rehearsal, he noticed how having all the men dressed in the old way caused the whole action to take on more power.

Another change had been more subtle. Since the minister was merely filling in for the director and had no pretensions about his theatrical calling, the actors had to work matters out themselves. Gradually, Hawkins came to guide their gestures and speeches. Being Jesus had something to do with it, since he was the main player, but because Hawkins had been reading all the Bible commentaries he filled in a lot of background and at the same time lent a sense of freshness, even urgency, to how they were to play their parts, how the play was to go.

The big night came and the large sanctuary was filled. For Hawkins, by this time, all the murmuring people had become the citizens of Jerusalem just before Passover. The front of the sanctuary had been completely darkened, and when the lights came on the disciples were in their places for the scene of the Last Supper. There were soft “ooohs” and “aahs” from the audience. Then the scene settled down to the dialogue between disciples and to questions addressed to Jesus. Finally Hawkins rose and broke the bread for those at the table, telling them that he very much wanted to eat the bread with them, but would not eat again until the kingdom of his Father had come. The same with the goblet of wine. “Pass this among you and drink, but I will not drink until my Father’s kingdom comes.”

After this, Hawkins dropped the bombshell: “The hand of one of you who will betray me is on this table.” The latecomer who had taken the part of Judas looked down like a scolded dog. “Woe unto the man who betrays me.” After this moment, the discussion turned to who was going to be boss after Jesus left the scene, and one or two of the disciples managed to get a laugh from the audience as they fussed and preened about their relative importance in the group. The scene turned serious again when Simon Peter insisted that he was going to prison with Jesus if necessary, this after Jesus had told him Satan was after him. The little scene closed with Jesus telling Peter that three times before the cock crowed again he was going to deny even knowing him.

The second scene was still in the upstairs room and largely of Jesus going over their years together, all the hard times and the good times. How, even though they had no money or even shoes, they had stuck together and their faith had sustained them. Now the testing would begin again in earnest. He was to be tested; so were they, for all his work was left up to them and he was counting on them. As Hawkins spoke, he felt a sadness. They would betray Jesus; he had betrayed his wife; the girl with the cat had betrayed him.

The last scene of this short play was set in the garden. The disciples were all on the left side of the stage and Hawkins on the far right. The potted palms gave a good semblance of a garden as Hawkins knelt to pray with his body facing forty-five degrees to the audience. Most of the stage was dimmed, with a soft spot on Hawkins as he began speaking quietly to his Father, asking Him if he wanted to change His mind about what seemed headlong and inevitable. That maybe what would serve best would be to go back to the countryside and continue to preach.

Hawkins remained quiet for a moment and then a shudder passed through him. His whole countenance changed, as the skin drew tightly across his facial bones, and the perspiration broke out on his forehead.

The silence in the sanctuary deepened, as if a vast abyss had appeared. The people in the audience were rapt, embraced as they were by the dark security of their vantage point and the intimate vulnerability they were privy to. Monica played the organ softly to close the scene.

Had this drama been elsewhere the audience could have released the tension with applause. Instead they flocked around Hawkins when the play was over. His face still glistened with perspiration and he seemed exhausted. Members of the congregation said several times what a natural actor he was. He smiled a little, but seemed like he was somewhere else, even disoriented.

Monica came from her place at the organ. Standing off on the edge of the admirers, she frowned slightly, looking worried. When the others moved away she asked anxiously, “Are you OK?”

“Yes,” coming back from where he had been. “Yes. I believe so.”

Leave a Reply