“War is hell,” and war is our permanent reality. War has been the companion of man since the beginning of recorded history, together with the need to justify waging it. Centuries before jus ad bellum was imperfectly codified in late-medieval Europe, the desire to make one’s cause seem righteous had become a regular companion of campaign planning. An unjust war was deemed dishonorable to Rome, making republican senators feel justified in punishing those who waged one—if the effort was not crowned by victory. Only rarely would the mask be discarded to reveal the realist essence: “The strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

In modern times that essence remains unaltered, but the rhetoric has been adjusted to the need to create domestic consensus for the bloodletting. At its crudest we have the “Polish attack” on the German radio station at Gleiwitz, in Silesia, on the night of August 31, 1939; or Stalin’s claim that Finland had plotted an attack on the Soviet Union in the winter of 1939-40. At a higher level of sophistication was Berlin’s blank check to Vienna—issued on July 5, 1914—to smash Serbia as a means of provoking the preventive European war against France and Russia that Wilhelmine Germany’s leaders had deemed necessary and winnable. At the highest level of complexity was FDR’s goading of the Japanese to attack Pearl Harbor as a means of enabling him to join the war against Hitler.

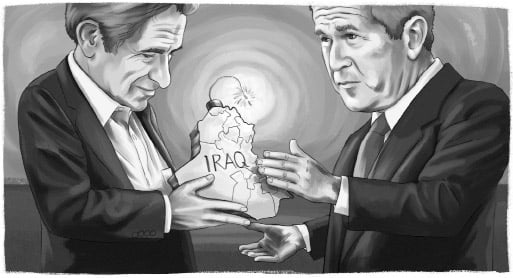

In terms of rhetorical spin, the war in Iraq belongs to the crude category. A policy determination was made first—Mesopotamia delenda est!—with the justification concocted on an ad hoc basis as we went along. Its four key themes have been weapons of mass destruction (WMDs), alleged terrorist links, democratization of Iraq and the Middle East in general, and social work (removing a brutal dictator, “liberating Iraqi women”).

The campaign for a second war against Iraq started 14 years ago. Founded in Washington in 1997, the Project for a New American Century (PNAC) began advocating U.S. intervention against Saddam Hussein as soon as it came into being, citing WMDs as the reason. In its open letter to President Bill Clinton dated January 26, 1998, PNAC said that, given the magnitude of the alleged Iraqi weapons threat, military action was the only option. The letter was drafted by Paul Wolfowitz, who was among its 18 signatories; others included Donald Rumsfeld, Richard Perle, Richard Armitage, and William Kristol. Testifying to the House National Security Committee in September 1998, Wolfowitz asserted that Saddam was reconstituting his “prohibited weapons capabilities” and demanded “a serious policy” that would “free Iraq’s neighbors from Saddam’s murderous threats.”

There was no proof that Iraq had any such capability; but in 2002 that objection was discounted by Rumsfeld in a phrase worthy of Hegel: “the absence of evidence does not mean the evidence of absence.” When no WMDs were found following the occupation of Iraq, Rumsfeld refused to admit that he had been wrong. “I have reason, every reason, to believe that the intelligence that we were operating off was correct,” he declared, “and that we will, in fact, find weapons or evidence of weapons programs that are conclusive.” Almost a decade later, his “every reason” is a known known: It was an act of blind faith.

The terrorist attacks of September 11 provided the neocons and their allies with a new theme. Within hours of the attacks, they were busy trying to insert the war against Iraq into the package of antiterrorist options. According to the final report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States (the “9-11 Commission”), that same afternoon Mr. Rumsfeld told Gen. Richard B. Myers, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, that “his instinct was to hit Saddam Hussein at the same time—not only Bin Ladin.” Secretary of State Colin Powell told the commission that within days of September 11 Assistant Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz had argued that Iraq should be attacked, but had no rational basis for the demand: “Powell said that Wolfowitz was not able to justify his belief that Iraq was behind 9/11. ‘Paul was always of the view that Iraq was a problem that had to be dealt with,’ Powell told us. ‘And he saw this as one way of using this event as a way to deal with the Iraq problem.’”

On September 20, 2001, PNAC sent a letter to President Bush stating that, “even if evidence does not link Iraq directly to the attack, any strategy aiming at the eradication of terrorism and its sponsors must include a determined effort to remove Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq.” The letter, signed by Bill Kristol and two-dozen leading neoconservatives—including Richard Perle, Robert Kagan, Charles Krauthammer, Martin Peretz, and Norman Podhoretz—argued that “failure to undertake such an effort will constitute an early and perhaps decisive surrender in the war on international terrorism.” The signatories went on to repeat the allegation of Saddam’s terrorist connections in hundreds of articles, interviews, and speeches all over the world.

The campaign had its willing abettors within the Bush administration. As Bob Woodward documented in his book Plan of Attack, Colin Powell was horrified to find that Vice President Dick Cheney, Wolfowitz, and Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Douglas Feith had established what amounted to a “separate government” in the Office of Special Plans, a shady outfit that Powell called “Feith’s Gestapo office.” Its sole purpose was to concoct “the most alarmist pre-war intelligence against Saddam Hussein and then stovepipe it to the White House via Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney, unvetted by the intelligence agencies.” Ken Pollack, a former National Security Council expert on Iraq, confirmed that the advocates of war “created stovepipes to get the information they wanted directly to the top leadership . . . They always had information to back up their public claims, but it was often very bad information.”

In reality the information was cut out of whole cloth. The alleged link between Saddam and terrorism was nevertheless adopted by the Bush administration as a key justification for war. Secretary Rumsfeld thus warned on November 14, 2002, “Within a week, or a month, Saddam could give his WMD to al-Qa’ida.” Former CIA Director George Tenet, testifying before the Senate Armed Services Committee, went further when he claimed that “Baghdad has a long history of supporting terrorism, altering its targets to reflect changing priorities and goals. It has also had contacts with al-Qaeda.” He added that “there is no doubt there have been contacts and linkages to the al-Qaeda organization.” The theme was picked up by President Bush on September 25, 2002, when he declared, in his unique idiom, that “Al Qaeda hides, Saddam doesn’t, but the danger is, is that they work in concert”:

The danger is, is that al Qaeda becomes an extension of Saddam’s madness and his hatred and his capacity to extend weapons of mass destruction around the world. Both of them need to be dealt with. The war on terror, you can’t distinguish between al Qaeda and Saddam when you talk about the war on terror. And so it’s a comparison that is—I can’t make because I can’t distinguish between the two, because they’re both equally as bad, and equally as evil, and equally as destructive.

In the aftermath of the occupation of Iraq, on May 1, 2003, Mr. Bush reiterated this position by declaring that “the liberation of Iraq removed . . . an ally of al-Qa’ida.”

The 9-11 Commission found “no credible evidence” of a meaningful link between Iraq and Al Qaeda, however. Flatly contradicting claims by PNAC after 1998 and administration officials after September 2001, the commission’s preliminary report released on June 16, 2004, said that Osama bin Laden had long opposed the Iraqi leader’s secular regime, and that his subsequent attempts to obtain help from Saddam were rebuffed. This conclusion reflected the consensus of the intelligence community. The findings were supported by top CIA and FBI officials who had been under intense political pressure before the war to establish such a link.

The commission’s report came but two days after Vice President Cheney made another assertion that a link between Saddam and Osama did exist, and one day after President Bush backed up Cheney’s claims. After the report was released, however, all “terrorist” claims stopped abruptly. The War Party shifted its focus to “human rights” and “democracy” as the real reason for the Iraq war. They took their cue from Paul Wolfowitz, whose testimony before the Armed Services Committee on April 20, 2004, did not mention any WMDs but focused entirely on the brutality of Saddam’s dictatorship.

The next justification for war was based on the claim that establishing peace and democracy in Iraq (and subsequently throughout the greater Middle East) was a key tenet of the “Global War on Terror.” As President Bush put it,

Some who call themselves “realists” question whether the spread of democracy in the Middle East should be any concern of ours. But the realists in this case have lost contact with a fundamental reality. . . . If that region is abandoned to dictators and terrorists, it will be a constant source of violence and alarm . . . [but] if that region grows in democracy and prosperity and hope, the terrorist movement will lose its sponsors, lose its recruits, and lose the festering grievances that keep terrorists in business.

Exporting democracy is not feasible outside of the framework of ideas that sustain it. Christian societies have been able to develop democratic institutions because of the Christian concept of governmental legitimacy, which accepts the possibility of two realms: “Render therefore to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and to God the things that are God’s.” In Islam there is no such distinction. It condemns as rebellion against Allah’s supremacy the submission to any form of law other than sharia.

“Democratizing the Middle East” was always bound to benefit hard-core political Islam, as has been amply proved by the fruits of the “Arab Spring.” After the second round of Egyptian elections, with the Islamists capturing over two thirds of the vote, it is clear that in Muslim countries the opposition to autocratic regimes comes not from secular reformers but from true believers who accuse those regimes of betraying the true faith. It is as if fervent Maoists, rather than pro-Western democrats, had provided the opposition to the Soviet-bloc regimes in the 1980’s. The predominant response in today’s Muslim world to the crisis caused by Western superiority is the demand for “Islamic solutions.” The perils of “spreading democracy” in a ground fertile for jihad are exceeded only by the folly of promoting jihad as a tool of short-term policy, which is exactly what the United States is doing in Syria.

In the end the war in Iraq proved self-defeating for the United States. It made Iraq safe for Shi’ite clerics, to the delight of their sponsors in Tehran. “We are ending a war, not with a final battle, but with a final march toward home,” President Obama told the soldiers on December 15, but it was not a march of victors pleased with a job well done. The withdrawal was formally over on Sunday, December 18. On the following day the Shia-led Iraqi government charged its Sunni vice president with running sectarian hit squads targeting government officials. The arrest prompted other Sunnis to boycott cabinet and parliamentary sessions. Within days three Sunni-majority provinces in central and western Iraq started demanding greater autonomy with a view to forming a separate entity, thus following the example of the Kurds in the north. A civil war is a distinct possibility.

The Iraq war has been a disaster for the United States, for the Iraqis, and for the stability of the region. All putative justifications were based on outright lies or gross errors of judgment. It was an unjust and unjustifiable war.

Leave a Reply