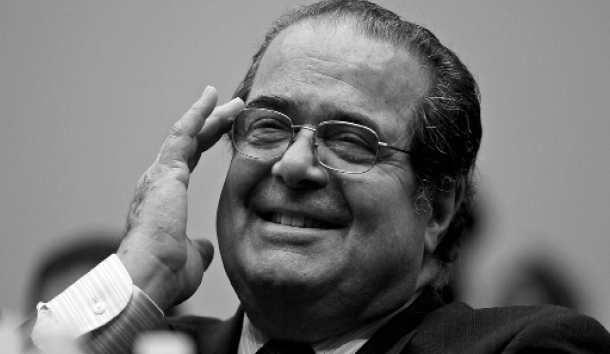

Who is to decide? This question animated Associate Justice Antonin Scalia, who died of natural causes in mid-February. He was the longest-serving member of the current Supreme Court. Nominated by Ronald Reagan in 1986, Scalia was known for his acerbic wit and fidelity to the text of the Constitution, as understood by those who ratified it.

When the Supreme Court deals with hot-button issues, politicians and pundits typically debate what the “right” policy result is. For example, leading up to Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), commentators argued about the desirability of an expanded understanding of marriage. Most asserted that if two people of the same sex declare their love for each other, then neither fundamental nor statutory law should stand in the way of the union. Very few questioned whether the Supreme Court was the right body to decide the issue. So long as the question is deemed important and some sort of constitutional claim can be pled, modern Americans assume that the final call belongs to nine unelected judges in Washington, D.C. They cannot comprehend that the process that is followed is often more significant than the ultimate policy determination.

This type of thinking (or lack of thinking) vexed Justice Scalia. “I am one of a small number of judges, small number of anybody—judges, professors, lawyers—who are known as originalists,” Scalia said in a 2005 speech at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. “Our manner of interpreting the Constitution is to begin with the text, and to give that text the meaning that it bore when it was adopted by the people.”

Scalia saw originalism as a check on judicial power. “You see, I have my rules that confine me,” Scalia explained. “I know what I’m looking for. When I find it—the original meaning of the Constitution—I am handcuffed.”

There are no shackles when one interprets the so-called Living Constitution. Adherents to this doctrine, as explained by Scalia in his book A Matter of Interpretation, view the Constitution as “a body of law that (unlike normal statutes) grows and changes from age to age, in order to meet the needs of a changing society.” And who determines when reformation is needed and what the adjustment will be? The people? Their elected representatives? No. “[I]t is the judges,” Scalia said, “who determine the need and ‘find’ that changing law” under the Living Constitution.

Many assume that Scalia objected to the Living Constitution because he opposed change—because he wanted to force the American people onto a Procrustean bed of 18th-century morality and thought. Quite the opposite. His real fear was not that the Living Constitution crowd would facilitate social change, but that they would seek to prevent it:

My Constitution is a very flexible Constitution. You think the death penalty is a good idea—persuade your fellow citizens and adopt it. You think it’s a bad idea—persuade them the other way and eliminate it. You want a right to abortion—create it the way most rights are created in a democratic society, persuade your fellow citizens it’s a good idea and enact it. You want the opposite—persuade them the other way. That’s flexibility. But to read either result into the Constitution is not to produce flexibility, it is to produce what a constitution is designed to produce—rigidity.

For example, proponents of homosexual marriage, despite enjoying much success in various state legislatures, resorted to the courts and constitutionalized gay marriage so that this issue is taken out of the political process. If ever the people realize that they acted hastily and foolishly in the embrace of gay marriage, change is prevented absent a decree from nine unelected justices sitting in Washington, D.C.

“The virtue of a democratic system with a First Amendment is that it readily enables the people, over time, to be persuaded that what they took for granted is not so, and to change their laws accordingly,” Scalia wrote in 1996 when dissenting from an opinion in a case wherein the Court essentially forbade government-sponsored, single-sex educational institutions. “That system is destroyed if the smug assurances of each age are removed from the democratic process and written into the Constitution.”

Scalia was always quick to point out that originalism was at one time a majority view of both the legal community and the American people. He highlighted the 19th Amendment, which gave women the vote in 1920. Had the Living Constitution been ascendant then, there would have been no rallies, political debates, or voting in the state legislatures on the amendment. In modern America, Scalia observed,

Someone would come to the Supreme Court and say, “Your Honors, in a democracy, what could be a greater denial of equal protection than denial of the franchise?” And the Court would say, “Yes! Even though it never meant it before, the Equal Protection Clause means that women have to have the vote.”

But in 1920, the people believed that the 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause meant the same thing it did when it was ratified in 1868. Everyone understood that it did not prohibit discrimination in the franchise—whether on the basis of sex, or on the basis of property ownership or literacy. “None of that is unconstitutional,” Scalia noted. “[T]herefore, since it wasn’t unconstitutional, and we wanted it to be, we did things the good old fashioned way and adopted an amendment.”

Scalia realized that even when originalism was the ascendant theory, judges could abuse their power. The difference between then and now, according to Scalia, is that “prior to the advent of the Living Constitution, judges did their distortions the good old fashioned way, the honest way—they lied about it. They said the Constitution means such and such, when it never meant such and such.” In the 21st century, judges “no longer have to lie about it, because we are in the era of the evolving Constitution. And the judge can simply say, ‘Oh yes, the Constitution didn’t used to mean that, but it does now.’”

The elected branches and the people are well aware that the High Court regularly engages in policymaking. This explains why the confirmation process for judicial nominees has become a street fight. In 1986, Scalia’s nomination received a 98-0 vote in the Senate. Everyone knew he was personally conservative and an originalist. Back then, we at least pretended that an ideal candidate for the Court would pay close attention to the Constitution’s text and give it the fair meaning it had when it was adopted. Today, the political parties nominate judges in light of the policy decisions they expect them to make. Republicans and Democrats try to pick lawyers who will write the new constitution in a manner agreeable to parties’ interests. There is no more pretending.

In some matters, Scalia was prophetic. In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), when the Court declared that homosexual sodomy is a fundamental right protected under the Constitution, yet disclaimed that this necessarily meant that homosexuals had a right to marry, Scalia called foul. “Do not believe it,” he warned. “Today’s opinion dismantles the structure of constitutional law that has permitted a distinction to be made between heterosexual and homosexual unions, insofar as formal recognition in marriage is concerned.” If moral disapprobation of homosexual conduct is no proper ground for prohibiting homosexual sodomy, then “what justification could there possibly be for denying the benefits of marriage to homosexual couples?” The answer, as revealed in Obergefell, is none.

Scalia called it like he saw it and did not pull punches. A good example is King v. Burwell (2015), when, in order for the text of the ObamaCare statute to pass constitutional muster, the Court held that the words “Exchange established by the State” really meant “Exchange established by the State or the Federal Government.” This legitimized the program’s creation of tax credits for federal exchanges, and saved ObamaCare itself.

Scalia rightly lashed out at the majority for rewriting a federal statute. It was “pure applesauce” and “interpretive jiggery-pokery.” He continued: “Much less is it our place to make everything come out right when Congress does not do its job properly. It is up to Congress to design its laws with care, and it is up to the people to hold them to account if they fail to carry out that responsibility.”

In the short term, there are ramifications for pending cases in light of Scalia’s death. Currently, there are only eight justices on the High Court, and ideological differences will likely result in 4-4 splits. When this happens, the decision of the lower court will stand. Pending cases dealing with unions’ ability to collect fees from nonmembers for collective bargaining, accommodation for religious organizations under the Affordable Care Act’s contraceptive mandate, and executive orders dealing with immigration matters will likely have different outcomes than they would have had Scalia lived.

In the long term, with a seat vacant, President Obama could have an opportunity to mold the Court into an institution that is solidly liberal for years to come. Shortly after Scalia’s death, the President was solemnly invoking the Constitution and promising to do his duty in nominating another justice. Of course, a hearing on a nominee before the presidential election will almost certainly not happen with the Republicans in control of the Senate. However, if Obama is shrewd enough to nominate a moderately progressive lawyer rather than a wild-eyed Jacobin, he might cause the Republicans to flinch. For instance, Judge Sri Srinivasan of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals was unanimously confirmed to his current post by the Senate in 2013. He has served in both Republican and Democratic administrations. It’s doubtful a President Hillary Clinton would ever nominate such a moderate candidate. Srinivasan is no Scalia, but neither is he a Stephen Breyer, the SCOTUS high priest of the Living Constitution.

A Republican victory in November would make matters even more interesting. Rumors have been swirling about the health of 82-year-old Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who has always been a solid vote for the liberals. Moreover, Anthony Kennedy, a Reagan appointee who often votes with the left wing of the Court, is only a few months younger than Scalia. If a Republican president could fill these two seats with reliably conservative jurists, then a conservative majority might exist for the foreseeable future. (Of John Roberts, Samuel Alito, and Clarence Thomas, the latter is the oldest at the relatively young age of 67.) But the Stupid Party does not have a good track record of nominating reliably conservative justices. Harry Blackmun, David Souter, and Anthony Kennedy are the most glaring failures of Republican presidents in the last 50 years.

Leave a Reply