Deep in the heart of man there is a need imprinted by nature that may very well be his basic difference from all other animals: Being a thinking one—i.e., an animal capable of self-awareness—man needs to be something meaningful in his own eyes, something which deserves to exist, possessed of a certain dignity. All men need to give some objective value to their lives.

Each must derive this value either from being an absolute end to himself—which amounts to playing God—or from drawing his personal, and possibly unique, substance not from himself but from playing a meaningful role in some kind of order of which he is only a part, but without which he would remain what a grain of sand is to a desert. Man is an animal longing to belong and to participate.

To satisfy this longing presupposes that man sees the world into which he must fit as something worth existing by itself. His quest for being induces the need for a reason for all things to exist as they are. He cannot help being a religious animal, because he ultimately aspires to having his place in the world—the place, Christians think, God Himself allotted him.

Now, for all men, the world is two-sided: It is a physical entity (each man is part of the natural world), and it is a social entity (no man is an island, unless he is a brute or a god). To achieve his own nature, man must manage to discover what may be his place in both sides.

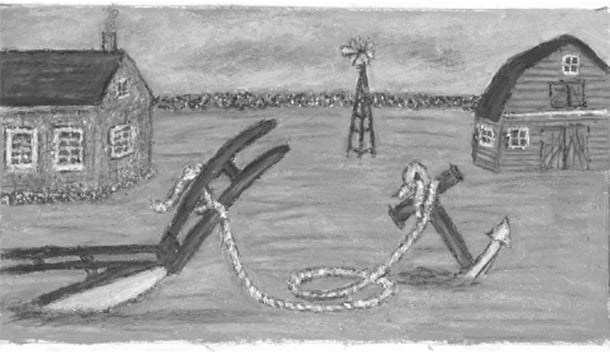

The most natural way for a man to feel part of nature is to be in contact with some soil, to be rooted in a plot of land. To escape being as a speck of dust, deposited where he is by the winds of life, whose insignificance is precisely what allows him to fit anywhere, he must find a place that is somehow his natural place, that somehow needs him. It is no happenstance that the aristocrats, men who were supposed to be the finest of men, used to bear the name of their land (e.g., Monsieur de Rochambeau). The reason is not that ownership of land was the main means of domination, as Marx would have it, but that it is natural for man to anchor his two feet to ground that is his own. (No one anchoring them on the concrete floor of his high-rise apartment is likely to believe the place was made for him.) Since the farmer must till his field for it to produce wheat, the field on which the spring wheat sprouts is to him what the painted canvas is to the painter: his personal enduring mark on earth. It even seems nature herself wants it to be his own particular place, for nothing natural is ever uniform, no parcel of land is ever strictly identical to the next.

To be rooted in a particular soil is not to be chained to a narrow horizon, as moderns would have it. On the contrary: How can the farmer, having sown his field with handfuls of seed, waiting for nature to reward him with bushels of wheat, not feel the world to be a cosmos in whose encompassing harmony he has a part to play, not believe God Himself wants him to live where his wheat grows?

Of all the elements in God’s universe, the soil is the one friendliest to man. The myth of Antaeus, the giant who grew stronger every time he was knocked down, is not merely a myth, nor is the Jews’ belief in a promised land uniquely theirs. The seas and the skies also appear as God’s work: They can be admired or loved, but in these elements no man has a particular place, neither to be born, nor to live, nor in which to play a role as natural as the farmer tilling his soil. Nor has any man a natural place in a town, which is only the meeting place of men who have chosen the rootless, nomadic, artificial life of all traders.

It is just as natural for each man to anchor himself in a history as in a landscape, to have his place in the flow of time as well as in space.

What is it to be a Christian if not to consider essential to man a desire for an eternal place in an eternal world? But this desire translates as a concern for one’s past and one’s future; it is natural to man to remember and be remembered, to need to be an heir and leave a legacy, to turn oneself into a somehow indispensable link between a past and a future, and not to remain a fly that does not outlive the summer. But one’s history is no history to anyone but oneself, and no man has a past or a future by himself. Which is why, since no one is as important to any other as to a member of his particular family, if a man has any allotted spot or any lasting existence in the eternal change of all things mortal, it is first of all as a descendant of his ancestors; in his living relatives’ thoughts, hopes, or memories; and as the prospective ancestor of future generations.

Though families may be self-centered, they are also the medium through which an individual is given a place in the history of his community. No one can personally relate to past events of his community except through the entity, his family, which experienced and survived them, and of which he is a part. Which is why a lasting nation is by nature an association of families: Individuals die; families endure. There are no national traditions where there are no family traditions, and having family roots is no narrowing of the individual’s vision. One could even claim that, since the past of his nation is, in turn, linked to the past of other nations, it is only by being a part of a particular history that men may ultimately relate to the history of mankind.

Finally, if man is a participating animal, there can be no propensity more natural in him than to be acknowledged as performing a useful function among his fellow men. Who can retain his self-esteem whom no one needs? But not every activity answers a natural need: a doctor’s or a baker’s does, but not a bookmaker’s. Now, what may be deemed a useful profession, a true calling? There is a simple criterion: An activity may be deemed truly significant when it is ennobling in the actor’s own eyes, when he regards it not merely as pleasant or financially rewarding, nor as a necessary inconvenience, but as an honor or even a duty to practice it (which is why for centuries professions tended to be hereditary)—in other words, when it does not only benefit him but also the entire community. Inasmuch again as man longs for participation it is natural that he be intent on having a true profession, on being to the community what an organ is to the body, neither dependent on his fellow citizens nor feeding upon them in a parasitic way. A natural community thus comprises a limited number of citizens, for, beyond a certain size of community, the role of each becomes so miniscule as to be unnoticeable.

This is not to extol a closed society, a narrow and selfish parochialism, as many would have it today. The very habit of being useful first to one’s fellow citizens naturally breeds the notion that for a man to exist means to be of service to his fellow men at large. There is no contradiction between a properly understood parochialism and a real sense of the brotherhood of man. The basic rule of natural solidarity is to be sure not to have missed any opportunity to help one’s immediate neighbors before assisting unknown and remote foreigners; the more this becomes the general rule of behavior, the fewer the chances the various communities will be in desperate need of assistance from others.

To sum up, there can be no man fully happy with himself who does not belong to a soil, a past, and a calling. And these three natural propensities, when fully acknowledged, make for all authentic communities, for three things make a community: an attachment to a soil, a reverence for tradition, and a spirit of service. Such communities may confederate themselves, but not beyond the point at which the whole gets too big and the individual too small. This means there is no general society of mankind. The only thing that may be universal among men is the propensity to participate in the life of the world, which is the essence of religious faith, but this translates into participating in worlds small enough for their participation to remain meaningful.

Modernity’s basic assumption is that man’s freedom supersedes his nature, that his nature is to make his own nature. This amounts practically to giving free rein to individual whims, passions, imagination, impulses, or vagaries, and radically precludes the idea that there may be natural bounds to his freedom—and therefore any idea that there might be any such thing as a natural society, other than that unnatural entity called the general society of mankind. All the main dogmas of our times appear geared to the subjective satisfaction of individuals, taken as essentially rootless and cosmopolitan beings: modern science, whose goal is not the contemplation but the domination of nature for the benefit of the unnatural, as well as natural, needs of any possible man; political economy, whether liberal or socialist, which caters to a nondescript individual’s unlimited consumption (and to the maximum enrichment of the strongest individuals or classes of individuals); democracy, whose ideal remains the improbable sovereignty of an absolutely free and therefore unspecified individual; religion, which becomes more and more sectarian, appealing to any individual’s tastes and supposedly spiritual fancies; culture, whose more and more appalling relativism or mere nihilism exonerates the individual from all possible norms, and particularly any natural one; the prevailing importance of commercial activities, whose basic law is to sell anything one may wish to anyone. The modern mentality seems to have sided with the unavailing glorification of a conception of man’s nature that used to be considered the corruption of his true nature, which is to belong. Theologically speaking, our societies are intrinsically sinful, because they revel in the implicit assumption that the only god who deserves a man’s devotion is his ego.

Inasmuch as there is such a thing as a nature of things and man, our societies are therefore doomed to self-destruction.

When a man is born a spiritual foundling and dies, for all purposes, a bachelor, when everything is equally worth doing, when anyone can live anywhere, then nothing and nobody is really worth anything, and indefinitely yielding to his passions ends up depriving man of any lasting satisfaction, if it does not drive him to the spurious drug-induced delights of oblivion. At some point the unwitting denial of a human nature becomes literally suicidal for mankind. This is glaringly obvious with homosexuality and abortion, but it is just as lethal with the spreading of urban agglomerations, for men are like apples: When stacked, they rot.

But the truth of the matter is that sin has been, is, and will remain tempting. Compared with the ease of bowing to one’s whims, to behave according to nature will always remain painful, if only because it involves the frugality that goes with local production and consumption.

What are the chances of returning to the womb of Mother Nature, and specifically to natural, modest, communal living? We are these days beset by the aforementioned modern abhorrence for seeing oneself as a being who must belong, the unexpressed loss of vital energy or meaningful goals of our societies, and the onslaught of more youthful cultures eager to overpower our old Christian one. Under these circumstances, one must wonder whether Western civilization has not run its course. This is no reason not to resist to the end, but no ground either for realistic optimism.

As for the immediate future, it is not that a sort of diffuse nostalgia for the old folkways cannot be found. But the feeling is usually perceived as more quaint than profound: To love folklore is fine, as long as one only indulges in it on weekends. The environmentalist dreams of a nonpolluting car, but he still wants a car. He wants to save the planet, but is it because he respects a natural order of things, or because he is afraid natural resources are limited? He wants to play the farmer, but does he realize the farmer has to obey the laws of nature more than any other man—or does he think that country living is hippie living, that living according to nature means God is dead and anything is permissible? Are the environmentalist leaders really after a return to the past of the Western world, its traditions and traditional beliefs, or after the disparaging of the West and its eventual demise?

The issue we are facing is exclusively moral and spiritual. If there could be a spiritual conversion (in the etymological meaning of the word), the rest would follow. But is this conversion in man’s hands? As far as I am concerned, on a human scale, there is no way to go except through a very modest, very narrow door: to keep voicing the laws of God’s nature, and to make up for the absence of full-fledged real communities by entering some more artificial ones united around the same creed, the same principles, such as what could be called “the Chronicles community.” Such purely spiritual or intellectual communities are of course desperately in need of a concrete substructure. But for the moment they represent our civilization’s last chance.

Leave a Reply