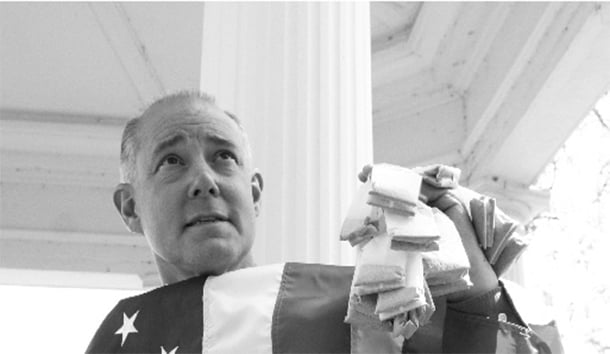

After 16 months, perhaps the best one can say for the Tea Party is that the contempt it originally provoked within the American establishment has turned to consternation. If the Tea Party were composed of real Indians, the elite would be understanding, if not exactly encouraging, and not in the least alarmed or offended. Since, however, the modern Tea Partiers are only white people got up in paint and feathers, the American ruling class finds itself compelled, by its own prejudices, neuroses, and—it may be—fears, to recognize a potentially dangerous threat.

Over the past three months the Tea Party has broadened the scope of its protest, in particular with regard to immigration, an issue that it had previously taken care to avoid. Before the passage in April of SB1070 by the Arizona state legislature, which makes it a state crime to be in the country illegally and requires police officers to check the immigration status of suspicious persons, the Tea Party had focused its attention largely on taxation. Two decades ago George Will, the Beltway’s idea of a “conservative” columnist, loftily dismissed tax complaints by asserting that Americans, in comparison with the citizens of European countries, in fact are undertaxed. That was priggish of him, but taxes, though onerous and unfair, are really not the most pressing evil the American citizenry needs to resist. Since SB1070, the Tea Party has loudly defended Arizona’s action, while simultaneously attacking and deriding the state’s eminently attackable and derisive critics, who have so far succeeded only in exposing themselves as ideologues marching under the slogan illegal immigration now, illegal immigration forever. More directly, the Tea Party has played an active role in a number of political primaries, and in one of them it enjoyed a glorious victory by bearing home the scalp of Republican Sen. Robert Bennett of Utah, an instructive example of a Republican-pseudo, from a party delegates’ vote. (Bennett, reflecting the long-standing position of the Mormon church, always eager to import converts from abroad, is a strong partisan of immigration “reform.”) In general, the Tea Party’s success in the primaries had been mixed before Rand Paul won the Republican primary in Kentucky, but no one denies that the Tea Party has been effective in pushing the Republican Party distinctly rightward. It is a relatively small, loosely organized, mobile, and very active force that has shown itself capable of pulling off harassing raids, a modern political version of Gen. Bedford Forrest’s Critter Company. Unfortunately, what is needed in the long run is the equivalent of the Army of the Confederacy, commanded by a latter-day General Lee. (Many historians, of course, consider Forrest to have been the greatest military genius of the War Between the States, while Lee and his army were ultimately defeated, though only after a protracted and nationally devastating war.)

The Tea Party, whatever its influence at present and no matter what its future may be, probably has less importance as a political agent than as a sign of the times, and perhaps even a bellwether. Something in America has changed since the election and inauguration of President Barack Obama, and the Tea Party is a symptom of that change. The first and most obvious cause is the fact of the United States having elected her first mulatto president since the founding of the Republic more than two centuries ago. The issue is less the President’s blackness than the alien quality his color, fairly or unfairly, gives him. One need not be “racist” to respond to newspaper photographs and film footage of Obama, standing behind a podium bearing the presidential seal, with feelings of simple incredulity. (Even George W. Bush, immediately after the election, confessed he had never expected he would live to see a black man in the White House.) For such incredulity, Obama is hardly to blame. He is, however, entirely blamable for his inability, or perhaps his refusal, to foresee the likelihood—indeed, the inevitability—of such a reaction on the part of the white majority population, and therefore for his failure to make account for it. No doubt, that failure is thanks in large part to his own self-bamboozlement, and to the self-delusion of his entourage, allowing the Obama campaign to fall for its own sentimental propaganda about the coming of a new postracial America. As journalistic commentators have been pointing out ever since, no such color-blind animal in fact exists, yet the President and all his men have continued to act as if the species had already been verified, awarded a taxonomic name, and set down in the pertinent scientific literature.

Obama, feigning humility or coyness or both, has always been quick to dismiss the election of a half-black man to the presidency as no big thing, yet it is, indeed, a very big thing. Certainly, it is too large to have been succeeded, in the space of a few short weeks and months, by a $787 billion stimulus, the bailout of several huge financial institutions, the federal acquisition of a major automobile manufacturer, and, later, the passage of a federal healthcare bill whose unintelligibility is equaled only by its obvious unaffordability. The result of such unabashedly socialist policies is Obama’s plummeting popularity (33 percent), the galvanizing of a Republican Party thought to have been as dead as William Jennings Bryan’s Chautauqua, and the Tea Party.

Liberalism as a political movement (it never was a political philosophy, for the very good reason that it fails to approach the level of philosophy at all) never made sense in spite of the fact that the majority of Americans since the War Between the States have been liberals, whether they knew it or not. It took what James Kalb calls advanced liberalism, coming in the last quarter of the 20th century, to bring the American public to a sort of political Great Awakening, in which they find themselves, somewhat groggily, shaking themselves and rubbing their eyes. Or rather, one half of the American public, the other having converted—as it seems, irredeemably—to the advanced-liberal ideology, which is really the old liberalism stretched and distorted and pummeled from its youthful naive falsity into senile surrealism. The arrival of advanced liberalism has divided the United States between the New and the Old America, a division that is unlikely to be resolved in the foreseeable future but is becoming, rather, more fixed and rigid. Liberalism in the era of Obama represents for the Old American culture what Islam does for the culture of Old Europe. “[B]etween us and you there is a great gulf fixed . . . ” Liberals blame an unenlightened reactionary mass for the divide, but in truth the fault is theirs, and all theirs. Advanced liberalism demands that people think, believe, and act in ways that it is simply unnatural for human beings to think, believe, and act, and it is unlikely that it will win over a greater proportion of Americans to those ways than it has managed thus far to do. The battle lines have been drawn. America is fated to remain a house divided against herself for many generations, and afterward to share the inevitable fate of all divided houses, which are by nature ungovernable, and hence unlivable.

A century and a half ago the United States wasted the greatest opportunity in American history to divide peacefully into two geographic sections, each left to go its own way. Our ancestors had their chance, and they threw it aside. (Had they not, the fastidious Yankees of our own time would enjoy the inestimable satisfaction of requiring the Neanderthal Confederates to obtain visas before traveling north.) For four terrible years, the United States suffered the War Between the States. That was terrible enough, but that was all it was—a conflict between two discrete opposing unions. Today, she faces the prospect of real civil war, a war among citizens that cannot be settled by the physical separation of the adherents of the two sides, who, to a greater or a lesser degree, are integrated one with the other across an entire continent. The day may yet come when America will rue the chance she long ago refused, to separate what Orestes Brownson called the personal or barbaric democracy of the South from the humanitarian democracy of the North. (He preferred the first kind.) The problem then was a simple one, and so was the solution. Today, it has become an impossible problem, for which there is no imaginable solution. Modern Americans do indeed exhibit a tendency to settle in communities according to their own kind—not just racially and ethnically compatible communities but politically agreeable ones as well. (One thinks of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and Salt Lake City.) But these demographic self-rearrangements are insufficient to the scope of the difficulty, save on a statewide basis, in which case the resulting blocs of states would be unlikely to enjoy a convenient geographic contiguity. Whatever the solution—if there is a solution—turns out to be, it is clearly impossible that the United States should continue as she is going, trapped in a state of radical instability and wracked by the most profound public dissensions and animosities that inevitably acquire a personal dimension.

The Tea Party, as I have said, is not an agent of political change. It is an expression of a widespread popular demand for a kind of political and social reformation that has yet even to begin to be formulated in a conscious and deliberate way and coupled to a political vehicle devised more or less expressly for itself: a collection of loosely affiliated raiding parties, not an organized army fighting for a determined collective goal. Thus, the need seems to be for the eventual identification of some such goal, and the creation of a political movement capable of achieving it. Unfortunately, the times are probably not ripe for these developments. John Lukacs’s maxim that change within democratic polities always comes slowly may be soon tested. The United States, indeed, has changed radically, and with radical speed, in the past 60 years, and no one can say where she is going (except to likely disaster) and how fast she is going there. For this reason, the Tea Party’s essentially reactive, ad hoc, short-term strategy may be just what is wanted, for now. Perhaps, following this strategy that is in fact no strategy at all, it may help to create a political climate in this country from which some big political thing may arise. The Tea Party, and whatever friends and allies it may succeed in scrounging up for itself, are unlikely to create a true political party and less likely still ever to control the government, while the prospect of their establishing a ruling elite, as Sam Francis hoped his Middle American Radicals might do someday, is a near social and political impossibility. The New Class rules because it is necessary to the New America it has created, and, so long as the New America survives, the New Class has nothing finally to fear from the Tea Party and its sympathizers. This raises the great question whether the New America is actually sustainable, socially, economically, and politically speaking; or whether, as Edward Abbey put it 30 years ago, our only hope might not be catastrophe.

It is certainly conceivable that a new spirit of resistance could rise in America, spread itself around the country, and achieve in time a more populist, or popular, alternative to the increasingly despised and despaired of system with which Americans are saddled and bridled today. But while it may be possible to recover, or recreate, something of the Old American political system, the Old American civilization is gone for good. We cannot look for a restoration of that, and to look, or hope, for such a thing is to court unreality, cynicism, and despair, as the Tea Party so often does by its demand that Old Americans should be given their country back. No political movement, not even the resurrection of the Founding Fathers, could possibly accomplish such a miracle. Christ raised Lazarus and Himself from the dead. He never raised ancient Israel, the Israel of judges and kings, or the Israel of His own time, Israel under the Roman Empire, and He never will—at least not before the end of time itself.

Even so, the past couple of years are beginning to loom as significant ones in recent American history. Something, I cannot help feeling (feeling, not thinking), has happened, and is happening, in America. In these two years, America’s rulers have learned, for the first time since Alexander Hamilton expressed his theoretical fear of the Great Beast, the People, to fear the mob—the New American Mob. That is a healthy thing for all Americans, the ruled and their rulers alike: the first in their freedoms and possessions; the second in their souls.

Leave a Reply