A Burkean political demeanor is no longer possible.

There may be a certain overcorrection occurring among those conservatives who are leaving the framework of libertarian-influenced conservatism. In the past, the conservative movement has adopted some of the liberalism inherent in the libertarian framework, but in leaving this behind, they may risk going too far the other way, and into a full-blown quest for pure power.

At least, this is the concern of my friend, the writer Ben Lewis, who has written a reflection on “Conservatism and the Problem of Power” at The Traditionalist, his Substack newsletter. I cannot help but think that his concern is directed in part at me and other former libertarians who have started to lean more in the direction of viewing politics in terms of power rather than principle.

Lewis is not a libertarian, so he sees participation in the culture wars as a legitimate function of statecraft. Unlike many libertarians, he see a role for the exercise of actual power by the state in issues that affect the common good. Despite this willingness to exercise political power in some circumstances, he also believes that “suspicion of power is a foundational tenet of conservative political theory.” Lewis suggests that to abandon this suspicion altogether in one’s acceptance of political power would constitute abandoning the “conservative mind” altogether.

Lewis then criticizes “the suggestion that politics can be reduced to a winner-take-all battle between inveterate enemies.” Here, he is indirectly taking aim at Carl Schmitt, the political philosopher whom I and many other former libertarians have studied with enthusiasm. Schmitt famously wrote that all political actions and motives boil down to the question of whether you are dealing with a friend or an enemy.

What struck me most about Lewis’s critique is that it seems also to reflect the differences Chronicles’ present Editor-in-Chief Paul Gottfried had with Russell Kirk during the 1990s. Kirk and Gottfried were mostly in agreement regarding the meaning of conservatism, especially as opposed to neoconservatism. Both men rejected the universalist-ideological neoconservatism of the postwar establishment right, and grounded their conservatism in place, people, and cultural heritage.

Kirk, however, would emphasize T. S. Eliot’s concept of “permanent things” and the enduring treasures of our past that could not ultimately be destroyed during the left’s long revolution. Gottfried, on the other hand, was less confident in the ability of Kirk’s conservative principles to resist the leftist assault in the late modern Western culture. Thus Gottfried once noted in a symposium in celebration of Kirk, published at the Kirk Center:

My quarrel with Russell has less to do with his conservative vision than with the application of that vision to the present age. In my view, Russell’s picture of a conservative order, as put forth in the first edition of The Conservative Mind, has no significant connection to political and social life for most of the current residents of the United States and Western Europe. And that might have been the case even when his book was published in 1953. Reading Robert Nisbet’s The Quest for Community about the disintegration of modern society, a consumerist culture, and the pseudo-scientific administrative state, a work produced at about the same time as The Conservative Mind, one obtains a more up-to-date sense of the course of modern Western societies than one does from Kirk’s magnum opus.

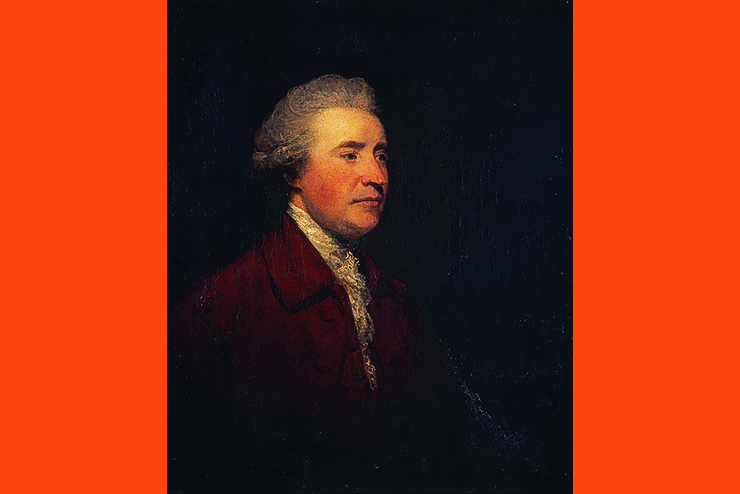

I believe this difference between Gottfried and Kirk leads us to the heart of Lewis’s call to disenchanted libertarians to resist overcorrection. He thinks we can still build upon the ideas of Edmund Burke, one of the great early figures in Western conservatism. In my contribution to Gottfried’s A Paleoconservative Anthology: New Voices for an Old Tradition, I emphasized three students of power who have become popular among “post-libertarians,” James Burnham, Carl Schmitt, and Antonio Gramsci. Of these three, only Schmitt might have been influenced by Burke. But Schmitt considered Burke’s worldview to have been rendered obsolete by the very force he warned against, the “new conquering empire of light and reason,” or political rationalism embodied in Jacobinism of the French Revolution.

In expressing his conservative hesitancy to use government as a weapon of power against enemies, Lewis quotes Burke:

All government, indeed every human benefit and enjoyment, every virtue, every prudent act, is founded on compromise and barter. We balance inconveniences; we give and take; we remit some rights that we may enjoy others; and we choose rather to be happy citizens than subtle disputants.

And he continues in this vein by quoting the eminent British Burkean, Sir Roger Scruton, who “criticized the kind of man who would ‘set himself against all forms of mediation, compromise and debate, and against the legal and moral norms that give a voice to the dissenter and sovereignty to the ordinary person.’”

The difference between conservative Kirkians, like Lewis, and more pessimistic reactionaries like Gottfried, can be traced to the question of whether Burke’s statement of government as a compromise and a sharing of power is still relevant today. While Lewis would consider this Burkean position this applicable to America’s current political situation, Gottfried believes this Burkean perspective no longer applies.

Burke also warned against the democratic revolutionary Thomas Paine, who called for massive political change. Burke thought such iconoclasts would overthrow what Englishmen had over the centuries created as their unique form of government.

Burke was very clear that in the beginning of kingdoms, politics was built on blood and violence—a sharp distinction between friends and enemies. Yet it was through the history and experience of nations that they could earn themselves the type of balanced and harmonious political system that Burke thought worth preserving. He warned, however, that seeking to tear down this achievement because of real or perceived imperfections would destroy England as a country. In one of the most beautiful passages in English letters, Burke wrote in Reflections on the Revolution in France:

All the pleasing illusions which made power gentle and obedience liberal, which harmonized the different shades of life, and which, by a bland assimilation, incorporated into politics the sentiments which beautify and soften private society, are to be dissolved by this new conquering empire of light and reason. All the decent drapery of life is to be rudely torn off. All the super-added ideas, furnished from the wardrobe of a moral imagination, which the heart owns and the understanding ratifies as necessary to cover the defects of our naked, shivering nature, and to raise it to dignity in our own estimation, are to be exploded as a ridiculous, absurd, and antiquated fashion.

What Gottfried, Schmitt, and others who have studied the political “science of power” would emphasize is that the explosion Burke warned about has already happened. We can no longer go back to Scruton’s Burkean framework, because Burke’s warnings from more than 230 years ago were not heeded. These critics are not enthusiastically advocating for the politics of the jungle; they are simply acknowledging that this situation has been forced upon us. It is not that Gottfried thinks Burke was wrong, it is that he was right—and that we should have listened, for his wildest fears came to pass.

None of this is to say that Lewis is wrong to cite Burke, Kirk, and Scruton about the problems of power. These men represent the very best of the conservative tradition; it cannot be denied that when the state absorbs the authority and hegemony of the civil institutions up into itself, the health of the nation is undermined. This is the essence of English political traditionalism.

But if Lewis senses in Gottfried, me, and other conservatives who reach this conclusion a dangerous rejection of late 18th-century political wisdom, this rejection stems from the recognition that the hour of the West’s destruction is closer than anything Burke, Kirk, or Scruton ever anticipated. I share with Scruton (and no doubt with Lewis) a deep pessimism about the trajectory of Western society. But I share with Gottfried and Schmitt a sober acceptance that we are living in a situation that is beyond the horizons of the old Burkean political demeanor.

If we have already lost the world picture advanced by Burke, Kirk, and Scruton, it is not the case that I consider them wrong but, painfully and with a somber heart, see the world as having been already remade. They were right, in other words, and we are now too late to heed them. And this rebirth of the world in an unlovely image means we must reconsider the role of the state in moving forward. It may no longer be possible to believe the illusion of “power gentle and obedience liberal.”

Leave a Reply