A century ago, journalist Walter Lippmann and progressive reformer John Dewey debated whether an informed public was possible, or just a herd to be driven by propaganda and the manipulation of “experts.”

In his Second Inaugural Address given in 1793, George Washington urged Americans, as a matter of first importance, to promote institutions “for the general diffusion of knowledge.” He added: “In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.”

Washington’s faith in the capacity of the public to be bearers of enlightened opinion is typical of educated men of his era; few seriously doubted the importance of a wider diffusion of knowledge among the citizens of a republic. Such optimism remained widespread throughout the century to follow. Only just before and after World War I did a few dissenting voices begin to find an audience. Foremost among these doubters was the redoubtable Walter Lippmann, whose The Phantom Public (1925) was a brilliant attempt to eviscerate the myth of what he called the “sovereign and omnicompetent” democratic citizen.

Competence, following Lippmann, may be understood as the capacity of the electorate to assimilate the knowledge necessary to make informed decisions about urgent political questions. In Lippmann’s skeptical view, virtually no one, no matter how well educated, could claim such competence—especially considering the ever-growing complexity of modern societies. Most of us possess some degree of narrow expertise: plumbers, car dealers, tax consultants, pastors, teachers, stock brokers, et al., can claim to be experts in their own fields, but no one can claim genuine expertise on all matters of national import. Yet democratic theory after the Enlightenment placed its faith in what Lippmann called the “mystical fallacy” of omnicompetence.

Lippmann’s dismantling of such democratic myths still echoes powerfully nearly a century later. Indeed, thoughful Americans in the age of the Internet are increasingly just as dubious as was Lippmann about the very idea of the “public,” which he viewed as a “phantom,” a hollow and dangerous fantasy which had its origins in Rousseau’s “General Will.” Stripped of its romantic aura, the public is nothing more than a vast aggregation of ignorant individuals who are presumed in their totality to possess not only sovereign omnicompetence but to be the vehicles of evolving historical truth (in the Hegelian sense).

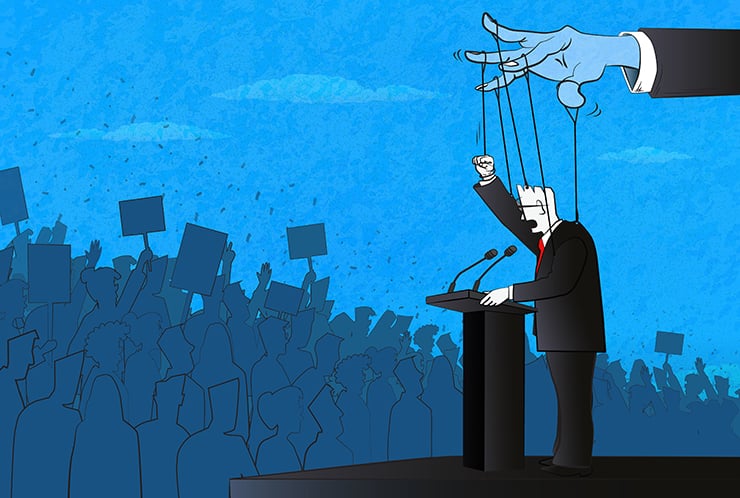

Yet, this truth bearing doesn’t happen spontaneously; it must be nurtured and shaped by the instruments of mass media. In fact, the concept of the public only emerged in the 19th century as a product of the press, which from early on engaged in what Lippmann called the “great simplification.” By this, he means that since the opinions of the masses of men “are almost certain to be vague and confusing … action cannot be taken until these opinions have been factored down, canalized, compressed and made uniform.” Thus, the seeming unanimity of a majority of the public on any given issue will be a work of artifice, manufactured by a collaboration of the press and savvy political operatives.

In his reflections on the role of the press in modern society, Lippmann’s argument resembled that of the great Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard in his Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age (1846). Kierkegaard was among the earliest thinkers to identify the press as the demiurge responsible for the fabrication of what he, coincidentally, termed the “phantom” public. (If Lippman borrowed the term from the great Dane, he did not say so.)

While Kierkegaard agreed that the press could channel and shape public opinion, it could not truly inform the public. Against the view that the “marketplace of ideas” (a more recent coinage) might somehow generate enlightenment, he regarded the daily infusion of news and opinion promulgated by the newspapers as demoralizing. The citizen-consumer of the news was inundated by sensational “information” disgorged with “unholy haste” by the newspapers of the day, including the left-wing Copenhagen weekly known as The Corsair, which routinely ridiculed Kirkegaard for his public criticism of its unethical journalism. Such “prattle-peddlers” were purveyors not of truth but “universal confusion.”

What we today call “disinformation” was already becoming common in Kierkegaard’s era. The dominant trend, he argued, “is continually in the direction of perfecting the means of communication so that the communication of nonsense can spread farther and farther.” In this fashion, the passive citizenry of a democratic modern polity is prepared by the media for its pivotal role at the ballot box!

We have traditionally believed that public opinion finds its highest expression in electoral rituals. We wait in solemn, orderly lines monitored by zealous volunteers and then make our furtive selections on a screen, satisfied that we have done our civic duty. But is an election, Lippmann asked, really an “expression of the popular will?” When we stand in the privacy of a voting booth and cast our votes, have we “expressed our thoughts on the public policy of the United States?” The notion is absurd. To call a vote an expression of the public mind is a vacuous fiction.

What the popular vote really amounts to is an alignment of forces: “The force I exert is placed here and not there.” Once that alignment is effected, voters resume their usual passive acquiescence. They do not articulate or execute policy. If they have aligned themselves with the majority, that is no guarantee that their choice has some ethical validation. The only compelling argument for elections is that they provide a safe outlet in “civilized society for the force that resides in the weight of numbers.” Majority rule is simply a “denatured” mode of civil war, and in this fashion, purely arbitrary force is avoided or sublimated.

In his early years as a journalist, Lippmann had been very much a man of the progressive left. Indeed, in his association with men like the progressive founding editor of the The New Republic, Herbert Croly, and the educational reformer John Dewey, Lippmann might be said to have been one of the leading lights of Progressivism, a movement that sought both a more vigorous administrative state and the expansion of democratic equality.

While Lippmann remained devoted to a centralized managerial state, by 1914 in his Drift and Mastery he was already beginning to abandon his confidence in the wisdom of the “common man.” In Public Opinion (1922) and in The Phantom Public he renounced the belief that participatory democracy might be an attainable ideal. The average man, he insisted, not only lacks (and can never obtain) the knowledge and perception necessary to take part in serious political decisions, but also has little interest in doing so:

The individual man … does not know how to direct public affairs. He does not know what is happening, why it is happening, [or] what ought to happen. I cannot imagine how he could know, and there is not the least reason for thinking … that the compounding of individual ignorances in masses of people can provide a continuous directing force in public affairs.

Yet if this is so, what or who can provide a “continuous directing force?” The politicians themselves? They are merely the ghastly offspring of an ignorant public and a compliant media. The answer can be reduced to a single word: expertise. If democracy is to survive, it must be placed in the elite hands of experts—particularly political scientists. As we shall see, Lippmann was not alone in placing social science at the center of his quest for Progressivist reform, but he was perhaps its most prominent advocate.

This is the point at which the reader, who has perhaps been nodding with approval thus far, will protest. While I wouldn’t care to endorse Lippmann’s solution, it will be useful to place it in context. He argued that elections are not fundamentally the consummation of participatory democracy, but rather an alignment of raw numeric force on one side or another. That alignment is compelled largely by party propaganda, which marshalls loyalty not so much to ideas as to emotional symbols, such as “law and order,” “a woman’s right to choose,” or “Make America Great Again.”

Leaders prepared to act arbitrarily to attain their ends, against all reason, create instability and provoke the spectre of civil insurrection. The highest interest of the public depends not on particular rulers but in the establishment of a “regime of rule.”

Thus, what is most essential is to train the public to align its emotive force with candidates “who are prepared to act on their reason against the interrupting forces of those who merely assert their will,” Lippmann wrote. What matters most, he argued, is stability. Leaders prepared to act arbitrarily to attain their ends, against all reason, create instability and provoke the spectre of civil insurrection. The highest interest of the public depends not on particular rulers but in the establishment of a “regime of rule.”

Yet how is the public to judge which leaders can be trusted to adher to a regime of rule? Lippman was quite aware that the solution to this problem is crucial. In a chapter entitled “Principles of Public Opinion,” he argues that the public must engage in a “sampling” of political candidates to assess whether they have demonstrated a capacity for following “a settled rule of behavior.” This sampling process must be guided by criteria that will enable the average voter to distnguish between “reasonable and arbitrary behavior.”

It is evident, however, that Lippmann had little confidence that the average man was capable of formulating such criteria. For this purpose, he proposed that it is the job of the political scientist to “devise the methods of sampling and the criteria of judgment.” Moreover, it would be the task of “civic education” to train the public in the use of these methods.”

Lippmann offered no explanation of how such a civic education would be administered. Presumably, he envisioned the training of Americans from an early age in civics and social studies classes designed to convey, in some easily digested form, the criteria devised by the aforementioned politcal scientists. If the reader is skeptical, he should be. It isn’t hard to imagine the legions of Gradgrinds who would inevitably infuse our civics instruction with mass-produced formulae for recognizing potential Donald J. Trumps—that is, great disruptors. As it happens, our public schools and colleges are today full of such men and women, even if they have not received the rigorous training that Lippmann advocated.

Clearly, all of this amounts to nothing short of the demolition of democracy. The role of the electorate in Lippmann’s “regime of rule” is reduced to a single aim: to ensure that the nation is always safely in the care of a cadre of elites, whose every decision will also be monitored by expert advisors. That would entail the electoral rejection not only of willful tyrants but of any leader whose aims might destabilize the “Great Society”—that is, the centralized civil society that has emerged since the late 18th century.

While political parties would not disappear in Lippmann’s new dispensation (what he terms “democratic realism”), the differences between them should not be profound. Otherwise, he asserted, “society would be constantly on the verge of rebellion.” Open debate is desirable, but, as he argued in Public Opinion, the real aim of debate in the public forum is to stir up the experts, “forcing them to answer any heresy that has the accent of conviction.” It is important to note that Lippmann places a great deal of trust in the disinterestedness of experts—a trust that seems more than a little presumptuous.

Two years after the publication of The Phantom Public, John Dewey responded to Lippmann in a work titled The Public and Its Problems. Unlike Lippmann, Dewey remained firmly within the liberal camp and remained a staunch believer in participatory democracy. He agreed with Lippmann’s convincing account of the myth of omnicompetence, but departed from his assumption that the public is a great aggregation of isolated individuals. Instead, the members of the public are always embedded in communities of one kind of another. What is most necessary for the survival of participatory democracy, he argued, is socially mediated knowledge, which happens “in association and communication” dependent upon tradition, “upon tools and methods socially transmitted, developed and sanctioned.” When the individual voter chooses his preferred candidate, he need not possess omnicompetent knowledge in the sense that Lippmann posited. He relies instead on the accumulated knowledge of his community, which he acquires through daily interactions with others.

Nevertheless, Dewey conceded that the expert must play a pivotal role in the complex Great Society made possible by industrialism. Given the new means of rapid communication and mobility, the socially mediated knowledge of a simpler age is no longer enough. The issues upon which the electorate must deliberate often require levels of specialized knowledge that the average man lacks.

Dewey noted that “local face-to-face community has been invaded by forces so vast, so remote in initiation, so far-reaching in scope, and so complexly indirect in operation that they are, from the standpoint of local social units, unknown.” Thus, he concluded that the only way to ensure the vitality of participatory democracy was to embed the cult of expertise ever deeper into local communities. Best known for his advocacy of extending democracy through the work of public schools, Dewey not surprisingly saw schools as the best venue for circulating expert knowledge among the electorate.

A century later, we are in a better position to see how much harm has been done by Dewey’s program for democratizing our public schools. However well-meaning he was, in hindsight it is difficult to understand how he could have been so blind to the long-term implications of that program. For public schools, perhaps more than any other institution in American life, have stripped local communities of their traditional loyalties and have encouraged generations of citizens to become ever more dependent upon experts who have now become a vast national bureaucracy.

Americans now are thrust at every turn upon the tender mercies of university-trained psychologists and other social scientists, who have no sympathy for our moral traditions. They have, in fact, worked assiduously to destroy those traditions. Against the views of both Lippmann and Dewey, we must demand a genuine restoration of our local communities, which is not only possible but urgently necessary. Our almost total dependency upon centers of power beyond our control was never inevitable, but was engineered systematically by the power brokers of the central state and its corporate allies. It is they who are the public enemies we must overcome—at all costs.

Leave a Reply