Probably the last thing that would have occurred to New York Gov. Eliot Spitzer on his way to meet “Kristen” in Room 870 of D.C.’s Mayflower Hotel was that both he and the Emperor’s Club VIP were under FBI surveillance for federal crimes—prostitution and a financial crime called “structuring.”

Traditionally, the enforcement of criminal law in the United States has been handled by the states. As a government of constitutionally limited power, Washington has typically exercised self-restraint, policing only crimes against itself, crimes taking place on government property, and crimes involving a substantial interstate element. However, in the past few decades, the federal government has increasingly created federal crimes that overlap state ones. There are now over 4,000 federal crimes in the U.S. Code.

Washington is so rich that it has grown careless: No local police, investigating a gun charge, would have acted like the U.S. marshals who went into the Idaho mountains at Ruby Ridge to arrest a separatist hermit—killing his 14-year-old son and wife—to bring him to trial, where he was ultimately acquitted of any serious charges, after the government had squandered ten million dollars. The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms (BATF) and FBI agents spent much more than that in a 51-day siege at Waco, Texas, before burning 82 Branch Davidians—men, women, and children. Local police probably would have foregone the siege and picked up David Koresh while he was out jogging. These gross injustices simply would not have occurred, had the regulation of firearms been left to the states. Washington, of course, is far less accountable than any state or local government—no one lost his job because of Waco or Ruby Ridge.

Every one of our Founding Fathers believed that ordinary crimes should be handled by the states, where local citizens could decide which acts to criminalize and could hold their elected representatives and law-enforcement officials accountable through their vote.

Before the American Revolution, English common-law judges could create crimes; they even made murder a common-law crime. One reason the Founding Fathers drafted a written Constitution that would limit the federal government was to make clear that federal judges could not do that here. The states, according to the Framers, held the police power to care for the welfare of their citizens. Federal crimes, they thought, would be limited to laws intended to preserve the federal government and carry out federal functions—against treason, espionage, tax and custom violations, counterfeiting—and laws respecting federal territory (enclaves, bases, vessels), where federal power is as comprehensive as a state’s police power.

Congress, in expanding the number of federal crimes, often cites the need to protect the channels of interstate commerce. The Supreme Court, for the most part, has supported and upheld the legislative branch in this endeavor. Thus, Congress has been able to create federal crimes by simply adding an interstate element to state crimes—kidnapping, firearms offenses, gambling, transportation of stolen vehicles, theft, arson, sexual exploitation of children, credit-card counterfeiting, money laundering, environmental transgressions, the theft of over $10,000 in livestock. This rationale has also led to a broadening of federal jurisdiction to encompass local robbery offenses under the Hobbs Act (an instance of robbery where the thief intends to spend the proceeds across state lines), the Extortionate Credit Transaction Act, and a range of offenses covered under state law by the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act (RICO). In 1994, Congress stepped up its federalization efforts by including acts of domestic violence that cross state lines, gang offenses, drug offenses, blockading of abortion clinics, possession of a handgun by juveniles, drive-by shootings, and a federal three-strikes rule. The Federal Program Bribery Provision imposes criminal penalties on any individual who attempts to bribe a member of a governmental entity, if said entity receives federal funding. Under this law, “it is now a federal crime for an auto mechanic to induce a public high school principal to hire him to teach shop class by offering a free car repair” (United States v. Sabri).

In 1996, Chief Justice William Rehnquist listed a series of criminal laws enacted during the George H.W. Bush and William Jefferson Clinton administrations which, “from the context in which they were enacted,” suggested that “the question of whether the states were doing an adequate job was never seriously asked”: The Anti-Car Theft Act of 1992, the Violence Against Women Act of 1994, the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994, the Child Support Recovery Act of 1992, the Criminal Enterprise Protection Act of 1992, adding arson to Title 18 in 1994. This last may have cost us the Twin Towers, since the FBI agent assigned to Zacarias Moussaoui could not devote his full attention to tracking his most important subject, thanks to some arson cases he was handling.

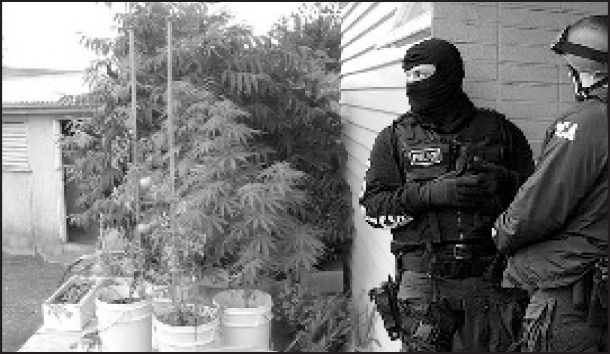

The Supreme Court could stop Congress from inventing federal crimes—at least where the people in the states in which they would be enforced do not consider the action criminal. In 1996, the California legislature passed the Compassionate Use Act, authorizing limited marijuana use for medical purposes. Two sick old ladies, with a doctor’s prescription, started growing marijuana in their backyards. Congress’s Controlled Substances Act, however, citing the Commerce Clause, makes the manufacture, distribution, or possession of marijuana a federal offense; so federal agents destroyed their crop of six plants.

In seeking to overturn the California law in Gonzales v. Raich (2005), Solicitor General Paul D. Clement cited Wickard v. Filburn (1942). Roscoe Filburn was found in violation of the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1938 because he grew wheat in excess of federal limits, although he said that the excess was only for personal use. Filburn’s actions, the Court determined, affected interstate commerce because, regardless of what he did with his excess, the surplus upset the balance of the national market.

But Justice O’Connor opined, “As I understand it, if California’s law applies, then none of this home-grown or medical-use marijuana will be on any interstate market.”

“I think,” Mr. Clement countered, “it might be a bit optimistic to think that none of the marijuana that’s produced consistent with California law would be diverted into the national market for marijuana.” Thus, backyard marijuana could have a “profound effect” on interstate commerce, justifying the federal government’s regulation of the ladies’ gardens. Yet the only way this “profound effect” could occur would be if, as Justice O’Connor pointed out, California failed to enforce its own law. In fact, wouldn’t legal homegrown marijuana have the opposite effect on interstate trafficking? At first, Justice Antonin Scalia seemed to think so:

Congress presumably wanted to foster interstate commerce in wheat, in Wickard v. Filburn. Congress doesn’t want interstate commerce in marijuana. And it seems rather ironic to appeal to the fact that home-grown marijuana would reduce the interstate commerce that you don’t want to occur in order to regulate it. I mean, you know, doesn’t that strike you as strange?

Nonetheless, the Court upheld the preeminence of the Controlled Substances Act over California law.

Most Americans probably did not know that dog fighting is a federal crime until Atlanta Falcons quarterback Michael Vick entered his guilty plea. It is a crime in Virginia, too, but the commonwealth had taken a more cautious and deliberate approach. Shouldn’t that have been the end of it? Isn’t one law-enforcement agency capable of handling a dog-fighting charge? In Vick’s case, the Virginia prosecutor made choices about how to proceed, and if the citizens of Virginia were dissatisfied with those choices, they could have held their prosecutor accountable. The citizens were never given that choice, however; instead, the feds swooped in and took matters into their own hands.

Federal prosecutors receive political benefits by cherry-picking high-profile targets that garner publicity. Indeed, James Comey, the U.S. attorney for the Southern District of New York who prosecuted Martha Stewart for making misstatements, was promoted to the second-highest position in the Department of Justice.

When Congress duplicates state law, it is creating the strong possibility of a violation of the constitutional prohibition of double jeopardy. The Fifth Amendment provides that no person shall be “subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb.” Americans instinctively believe it is wrong to try a person twice for the same crime. The Fifth Amendment traces to early Western history—at least to the medieval Church, which had the canon, “Not even God judges twice for the same act.” If a federal jury acquits an accused bank robber, it seems obvious that the Fifth Amendment is violated if the state in which the alleged crime occurred then tries and convicts him under its own statute. Amazingly, the Supreme Court has long held that federal and state prosecutors can try the same act consecutively till one gets it right. The Court, in an astonishing fiction, reasoned that the defendant in United States v. Lanza (1922) “committed two different offenses by the same act.” This theory is called the “dual sovereign doctrine.” Thus, in Bartkus (1959), the defendant was tried and acquitted of bank robbery in federal district court. The federal government could not retry him. Instead, it could “instigate and guide,” as the Illinois attorney general conceded, a state trial on robbery which led to the previously acquitted person getting a life sentence. The Supreme Court approved the successive prosecutions: “[I]t cannot be truly averred that the offender has been twice punished for the same offense; but only that by one act he has committed two offenses, for each of which he is justly punished.” Or, in this case, justly acquitted and then justly punished. Was one of those decisions wrong? The “dual sovereign doctrine,” despite its absurdity, is well settled. Indeed, for many years, the Court has not considered the states sovereign for any other purpose.

The Los Angeles police officers involved in the Rodney King case were acquitted in a state trial. The American Lawyer monitored the trial and concluded that the verdict was reasonable and largely justified. Then, the George H.W. Bush Justice Department retried and convicted the officers on federal civil-rights charges. Failed local criminal prosecutions can often be retried as federal civil-rights cases. It is up to the untrammeled discretion of the U.S. attorney general.

Some federal crime statutes have an imperial tone—they criminalize affronts to the dignity of the government. The Alien and Sedition Acts (1798) made it criminal to criticize a government official. Thomas Jefferson, when elected President in 1800, pardoned and released those convicted under the acts and stopped all ongoing prosecutions. He explained that the law was a

nullity, as absolute and as palpable as if Congress had ordered us to fall down and worship a golden image; and that it was as much my duty to arrest its execution in every stage, as it would have been to have rescued from the fiery furnace those who should have been cast into it for refusing to worship the image.

Perjury—swearing to a false statement—is a serious crime. The lawyers for Major League Baseball pitching titan Roger Clemens should have carefully advised him before his recent testimony. Even if his lawyers did not, every sports-radio program in America was warning him of the dangers. The oath gives the person notice that the matter is serious. It is said of some mafia figures, “He never lied, except under oath,” but for most people, the opposite is true. The world could probably not survive if everyone was totally honest all the time.

And yet, thanks to federal law, any statement you make to your congressman could be treated as an oath. Section 1001 of Title 18 makes it a felony if any person “in any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States, knowingly and willfully . . . makes any materially false, fictitious or fraudulent statement or representation.” You may be imprisoned for five years for this violation. The statute applies even if the statement is not sworn, there is no underlying crime, and there is no Miranda warning letting you know that talking to the congressman or investigator may be dangerous to your liberty.

Americans were recently informed that one percent of our fellow citizens are in jail. If the federal government consistently applied Section 1001, that figure could rise to 25 percent—maybe higher. At some point, citizens—considering the risk—might just stop talking to the government. Of course, the Department of Justice does not consistently enforce federal law. It just falls whimsically on those with bad luck. And the federal police force has total discretion to decide who has bad luck. For example, Washington wanted to make a Securities Act insider-trading case against Martha Stewart but could not find enough evidence. But she had made some misstatements along the way, so federal attorneys decided to prosecute her under Section 1001. She had bad luck, so she spent a year in jail.

Criminal investigations, as all investigators understand, are particularly prone to dishonest answers. A tax evader, for example, is likely to tell the IRS agent that he did not take any cash for signing baseballs at the card show. Because of Section 1001, if the IRS can make its case, the government can imprison him for five years for tax evasion and another five for the false statement. Section 1001 tacks another five years onto every crime in the book for every time the criminal said he did not do it.

In Brogan (1998), Section 1001 was attacked as ridiculous. Justice Scalia had to concede that the section creates a certain lack of balance since the reverse is actually deemed permissible—that is, federal agents can make knowingly and willfully false statements to you. (“Your buddy has already confessed.”) Nonetheless, Justice Scalia upheld the statute and referred anyone who might object to Congress: “Courts may not create their own limitations.” Judicial restraint is not always that helpful.

Far from restraining Congress, the Supreme Court has supported its experiment with general criminal law. The Court has allowed the invention of crimes supposedly based on the trade and spending powers. It has authorized successive prosecutions for the same crime in total defiance of the Fifth Amendment. It has authorized the creation of crimes where the behavior may be deplorable but is not criminal in any normal sense of the word. The federal court consistently upholds the federal power.

Worse still, in allowing Congress to create an ever-expanding federal police force, the Court had to know that Congress never intended its 4,000 laws to be enforced consistently. They provide unaccountable federal prosecutors the discretion to act if they see fit. Admittedly, some discretion is necessary in the law-enforcement process; but untrammeled and unreviewable discretion means a government of men, not of law.

Leave a Reply