Imagine a magazine that argued that the central symbol of Judaism was inextricably bound up with monstrous evil, claimed Judaism’s holy writings were lies, criticized what Jews believe and demanded they change their beliefs, attacked Judaism’s most important holidays, asserted that Judaism was directly responsible for one of the most horrific slaughters in history—and declared that anyone who questioned Judaism’s responsibility for that great crime was a liar or a bigot. An impartial observer would be forced to conclude that such a magazine harbored an animus against Judaism.

It is difficult to imagine such a magazine even existing in the United States, much less garnering any respect or prominence. If one substitutes Christianity for Judaism in the preceding paragraph, however, he will have to admit that there are magazines that publish all those arguments. Indeed, they are among our most prominent and respected journals of opinion: the New Republic (the fountainhead of neoliberalism) and Commentary (the fountainhead of neoconservatism).

Examples of Christophobia may be found in many other precincts of opinion journalism. Just before Christmas, in a column criticizing Episcopalians intent on maintaining orthodox Christian teaching on homosexuality, the Washington Post’s Harold Meyersohn attacked “the Catholic Church’s inimitable backwardness.” Slate has observed Christmas by describing the Gospel accounts of the Nativity as “legendary, contradictory, and ahistorical”; enumerating such “perennial yuletide joys” as “harried trips to mobbed shopping malls, wasteful spending on pointless presents, spikes in depressive and suicidal feelings”; and prominently featuring a column by Christopher Hitchens describing Christmas as “vile and insufferable.” There probably is no more zealous Christophobe in opinion journalism than Hitchens, who remains faithful to the Bolshevik ideal precisely because the Bolsheviks were so good at killing Christians. As Hitchens told PBS, “one of Lenin’s great achievements . . . is to create a secular Russia. The power of the Russian Orthodox Church, which was an absolute warren of backwardness and evil and superstition, is probably never going to recover from what he did to it.”

Precisely because of their intellectual prominence, there is no denying the important contributions to Christophobia made by Commentary and the New Republic, especially the latter. Indeed, even as Commentary has begun to tone down its Christophobia in recent years, the New Republic has gone in the opposite direction, enthusiastically spearheading the campaign to censor Mel Gibson’s Passion of the Christ—which was, in essence, an attempt to censor the public expression of Christian beliefs—and observing Christmas this year by republishing on its website economist James Henry’s 1990 essay “Why I Hate Christmas,” which argued for “an experimental two- to three-year moratorium on the whole affair.” And the New Republic’s owner, Marty Peretz, just cannot seem to restrain himself. On October 9, 2006, he published an online essay attacking Norman Finkelstein, which, because Finkelstein is a professor at DePaul, also included Peretz’s claim that all Catholic colleges are mediocre, his observation that fascism was “a recognizable Catholic tradition,” and his assertion that the Catholic Church was complicit in the holocaust. Characteristically, Peretz began this offensive column by stating, “Please, I don’t mean to offend anyone.”

The claim that the Catholic Church was complicit in the holocaust is perhaps the cornerstone of contemporary Christophobia. Indeed, it has become a commonplace in our culture. As Sir Martin Gilbert observed in an essay in the July/August 2006 American Spectator,

That the Pope and the Vatican were either silent bystanders, or even active collaborators in Hitler’s diabolical plan—and “rabidly anti-Semitic” . . . has become something of a truism in Jewish educational circles, and a powerful, emotional assertion made by American-Jewish writers, lecturers, and educators.

There is reason to believe that the KGB was responsible for these smears. A high-ranking defector from Rumanian intelligence, Lt. Gen. Ion Pacepa, recently alleged that Rolf Hoch-huth’s play The Deputy, which first popularized these charges against Pius XII, was part of a KGB plot to discredit the wartime pontiff and the Catholic Church.

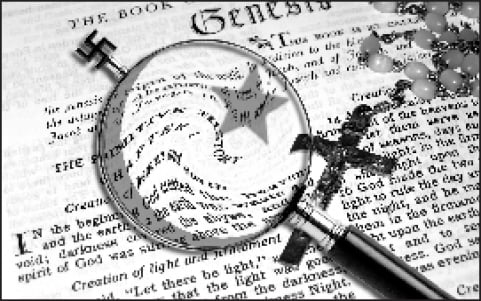

If the KGB wanted to blame Christianity for the holocaust, it was hardly alone. In the early 1980’s, Commentary printed essays by Henryk Grynberg, Ruth Wisse, and Hyam Maccoby arguing that “The plain fact [is] that the Holocaust was prepared and caused by Christian anti-Semitism” and that “The delegitimation of the Jews has become one of Christianity’s most lasting legacies in the modern world.” The most radical of these essays was Maccoby’s, which argued that “the Nazi episode” was part of “an unbroken historical connection in Christendom,” that “the metaphysical hatred of Jews” was “endemic in Christendom,” and that the antisemitism in Christianity derives “from its central doctrine and myth, the crucifixion itself.” Maccoby thus became one of the first (if not the first) of many writers to blame the Cross for the swastika.

Maccoby even blamed Islamic antisemitism on Christianity: “It is true that in recent years Muslims, out of political motives, have begun to demonize Jews, but in doing so they have had to draw their material from Christian sources.” Similar arguments have been made by the historian Bernard Lewis and the Anti-Defamation League’s Abe Foxman, who has claimed that “the current explosion of anti-Semitism in the Moslem Middle East is fueled largely by myths and doctrines that originated in Europe.” So great is the desire to blame the Church that She is even held responsible for the attitudes of a people who, since the beginning of their religion, have been attacking and attempting to subjugate both Christians and Jews, and whose scripture contains passages explicitly enjoining the killing of the same.

Despite the absence of any New Testament passage urging comparable violence by Christians, writers at Commentary have long expressed disdain for the New Testament. In 1992, Hyam Maccoby reviewed a book by a liberal Catholic priest and was thrilled that it “questions the historical truth of the Virgin Birth of Jesus, the perpetual virginity of Mary, the birth of Jesus in Bethlehem in a manger attended by Magi”; he was disappointed, however, that the author “refuses to allow that the Virgin Birth is derived from Hellenistic mythology.” In 2001, Robert Wistrich gave a very positive review to James Carroll’s Constantine’s Sword and attacked the “web of multiple distortions woven into the primal Christian narrative that would fuel anti-Semitism through the centuries.” Wistrich also wondered “how a Church that has not even come to terms with its own complicity in the most terrible event of the 20th century can still continue to proclaim that there is only one way to salvation.”

The arguments of Maccoby and Wistrich would be taken to their logical conclusion in a 24-page article by Daniel Goldhagen in the New Republic (“What Would Jesus Have Done?”). Goldhagen begins his vituperative screed by asserting that “the main responsibility for producing this all-time leading Western hatred lies with Christianity. More specifically with the Catholic Church.” He ends by asking, “what should be the future of this Church that has not fully faced its antisemitic history, that still has antisemitic elements embedded in its doctrine and theology, and that still claims to be the exclusive path to salvation?” A hint at Goldhagen’s answer is found in his fulsome praise of James Carroll, whom even Robert Wistrich recognized as making “theological demands [that] would involve not a reformation of the Church but its virtual dissolution.” Indeed, in his essay, Goldhagen denounces both the Cross, a symbol he sees as essentially antisemitic, and “the many historical fabrications and calumnies about Jews contained in the Christian Bible.” If Christianity is founded on lies and its central symbol is evil, what good is it?

Goldhagen is relentless in his extremism. He labels both Pius XI and Pius XII as antisemites, and he brands Pius XII as a “Nazi collaborator.” He claims that “[t]he Catholic Church . . . greeted many aspects of the Germans’ pan-European eliminationist assault on the Jews with approval, sometimes even with enthusiasm,” and that “[t]he Church was obviously content enough to watch more or less passively as the rest of Europe burned and the Germans pitilessly exterminated the Jews.”

Far from recognizing the extremism of his views, Goldhagen portrays himself as a lonely and persecuted acolyte of truth: “[S]peaking the truth about Christianity and antisemitism, and especially about Christianity and the Holocaust, is too rare.” Goldhagen’s firm grasp of reality is shown in his claim that the focus on Pius XII’s wartime record is, in essence, a clever Catholic ruse designed to divert focus from the real villain, the Church Herself, giving “the Church’s defenders [the] strategic victory of whitewashing the Church’s past.” Goldhagen contends that those who do not share his views are liars and bigots, writing that the claim that the Nazis’ antisemitism was not based on Christianity is “one of the most glaring public falsehoods of recent times” and that “only an antisemite and a historical falsifier can be counted upon to present Pius XII in the glowing manner required for canonization.”

Neither Goldhagen nor the New Republic has retreated from Christophobia. In fact, Goldhagen amplified his charges in the magazine three years later, in an article attacking the Catholic Church’s treatment of Jewish children rescued from the holocaust. (The fact that any such children existed—much less in the “thousands”—would have come as a surprise to anyone who based his knowledge of the holocaust on Goldhagen’s earlier essay.) This time, Goldhagen attacked Pius XII’s “criminal role during the Holocaust” and claimed that Pius XII “systematically spread . . . hatred and bigotry against a people while they [were] being persecuted and slaughtered,” “approv[ed] Nazified race laws persecuting an entire people,” and “fail[ed] to command bishops and priests . . . not to participate in the deportation of tens of thousands of people to their death.” Such hysteria is rarely seen in the pages of a respected magazine and would never have been tolerated had it been directed at a target other than Christianity.

Goldhagen’s essays are replete with lies and riddled with omissions. There is no evidence at all that Pius XII was “systematically spreading hatred and bigotry” against the Jews during the holocaust. The claims that Pius XII approved “Nazified race laws” and allowed “bishops and priests” to “participate in the deportations of tens of thousands of people to their death” are references to Slovakia, where a priest, Jozef Tiso, was the president. The Vatican, however, repeatedly protested against Slovakia’s passage of anti-Jewish laws and the subsequent deportation of Slovak Jews; the Slovak bishops issued a pastoral letter against the deportations; and the deportations were stopped after these successive protests. In fact, the German envoy in Slovakia, Hans Ludin, complained to Berlin that “The process of evacuation of Jews from Slovakia is presently at a standstill. Due to the influence of the Church and the corruption of individual officials, approximately 35,000 Jews were given special identification papers. On these grounds they are not required to be evacuated.” The deportations of Slovak Jews did not resume until October 1944, after the Germans had essentially seized control of Slovakia and the identity papers issued by Slovak officials were powerless to save anyone.

One would never learn from Goldhagen’s essay that, during World War II, Vatican Radio denounced “the immoral principles of Nazism” and the “wickedness of Hitler,” informing its listeners that “Hitler’s war is not a just war and God’s blessing cannot be upon it.” One would also not learn that many churchmen honored by Israel for saving Jews gave credit to Pius XII, including Giovanni Montini (later Paul VI), Angelo Roncalli (later John XXIII), and Pietro Cardinal Pallazini, who said “the merit is entirely Pius XII’s, who ordered us to do whatever we could to save the Jews from persecution.”

One would search in vain for a citation of Anglican historian John Conway, who concluded, after reviewing the records of Vatican diplomats during World War II, that “the picture that emerges is one of a group of intelligent and conscientious men, seeking to pursue the paths of peace and justice, at a time when these ideas were ruthlessly being rendered irrelevant in a world of ‘total war.’” Among the many places where these diplomats worked to save lives was Hungary, where, according to Hungarian Jewish historian Jeno Levai, “in the autumn and winter of 1944 there was practically no Catholic Church institution in Budapest where persecuted Jews did not find refuge.”

Goldhagen claims that Pius XII “did . . . not lift a finger to forefend the deportation of the Jews of Rome and other regions in Italy.” In fact, Pius XII sheltered 3,000 Jews at his summer residence at Castel Gandolfo. Pius’ example was followed in churches, convents, and monasteries throughout Italy. As a result of such efforts, 85 percent of Italy’s Jews survived the war, one of the highest percentages of any country occupied by the Nazis. Later, when Rome’s chief rabbi Israel Zolli converted to Catholicism, he took as his baptismal name Eugenio, to honor the Pope born Eugenio Pacelli.

Quite apart from the many falsehoods and omissions that characterize his essays, Goldhagen’s attempt to blame Christianity for antisemitism and the holocaust fails because it is contradictory. In his first essay, Goldhagen claims, on the one hand, that “Antisemitism . . . has flourished in all environments, outliving historical eras, transcending national boundaries, political systems, and modes of production” and, on the other, that “the main responsibility for producing this all-time leading Western hatred lies with Christianity.” It is hard to see how Christianity can be blamed for such a pervasive phenomenon, which predated Christianity in the ancient world, has also existed in the Islamic world, and has flourished among Europeans who disdained Christianity, including Hitler. Indeed, Norman Ravitch, analyzing Christian antisemitism in Commentary, admitted that “It is almost impossible to decide whether Christian anti-Semitism was merely a legacy from the ancient world . . . or whether Christian teaching developed a violence rarely found in the pagan world.” Nor does Goldhagen explain how, if Christianity was responsible for the holocaust, the mass murder of Europe’s Jews had to await a time when Christianity was on the wane.

Goldhagen also fatally undermines his case by admitting that the Dutch bishops vigorously protested the Nazi treatment of the Jews, and that the Nazis retaliated by deporting Dutch Catholics (but not Dutch Protestants) who had converted from Judaism. As Goldhagen writes, “the Church quickly learned that these Catholics were doomed regardless of its protest.” But if the Church could not save Catholics from murder by the Nazis, as even Goldhagen admits, how could She possibly stop the slaughter of Jews? Indeed, among Hitler’s many victims were thousands of Catholic clergy and religious, including bishops and 3,000 priests from Poland alone.

The simple truth is that Goldhagen and his fellow writers in the Christophobic press blame Christianity for the holocaust because they want to, because a living Church is a far more satisfying villain than the dead ideology that was actually responsible. If Pius XII actually had been a “criminal” and a “Nazi collaborator,” he would have done the kinds of things that collaborators and criminals actually did: ordered those under his authority to round up Jews and send them to death camps; forbidden Catholics to help Jews; and instructed Catholics to assist the Axis and oppose the Allies. It is absurd and offensive that Pius XII and the Catholic Church are treated as if they had actually behaved like this, instead of doing what they did—saving thousands of Jews from the holocaust, possibly up to 860,000, in the estimate of Israeli diplomat and scholar Pinchas Lapide. There is room for debating what else the Church might have done to abate the consequences of the Nazis’ murderous fury; there is no room for suggesting, as both neoconservatives and neoliberals have done, that the Church and the Nazis were essentially on the same side, that the Church was “complicit” in the Nazis’ crimes.

It was not Christianity that made the holocaust possible, but the decline of Christianity. As even Hyam Maccoby admitted, what gave rise to the holocaust “was the release afforded by Nazism from all vestiges of the restraint imposed by Christian morality.” It is far easier these days, however, to blame Christian “hate” than to praise “the restraint imposed by Christian morality.” Indeed, much of the elite press is eager to chip away at what remains of “the restraint imposed by Christian morality,” especially in the area of sexual morality. And so for many years to come, Christians should continue to expect intemperate, hateful, and ignorant attacks on the Faith that created Western civilization.

Leave a Reply