Few realize that the largest Protestant school system in the United States is operated by the Lutheran Church—Missouri Synod. With 1,018 elementary schools and 102 high schools sharing a combined enrollment of 149,201 students, it is an impressive educational endeavor. Beyond the United States, Lutheran schools in Canada, South America, Africa, Australia, and even such remote countries as Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan have been influenced to one degree or another by Missouri Synod theology and pedagogy.

The early history of this school system is not just an interesting chapter in educational history but a good case study on how Christian schools can prepare children to be participating members of American society while retaining a strong commitment to their faith and community.

In 1839 a group of approximately 750 Lutherans from Saxony arrived in St. Louis. Fleeing the theological liberalism of 19th-century Germany, their goal was to establish an orthodox Lutheran colony in North America. One of the remarkable features of this group was their commitment to education. These immigrants believed that in order to rear their children according to the dictates of their faith, it was essential to have schools that were independent of state control. Thus, less than one year after arriving on these shores, they established a classical Lutheran academy, or gymnasium, that was true to their theological traditions. According to an announcement placed in the local German newspaper, Anzeiger des Westens, this school was to teach everything that was “necessary for a true Christian and scientific education.” The curriculum for this new school was ambitious. It included Latin, Greek, Hebrew, German, French, English, history, geography, mathematics, physics, natural history, philosophy, music, and drawing. In September 1839 classes began in a log cabin with the barest of teaching materials and with an enrollment of seven boys and four girls. This was not the only school that they established. In fact, almost every congregation ran its own elementary school, resulting in near universal education within this Lutheran community at a time when fewer than 20 percent of children in Missouri completed an elementary education.

Eight years later, the Saxon immigrants joined together with other like-minded Lutherans to form the “German Evangelical Synod of Missouri, Ohio and Other States,” commonly known as the Missouri Synod. Their commitment to education was integrated into the constitution of the synod, thereby laying the foundation for an extensive, organized school system.

Schools were established at an astonishing rate. In 1847, the year of the founding of the synod, there were 16 congregations with 7 teachers and 7 teaching pastors serving 14 schools with a total enrollment of 764 students. Twenty-five years later, there were 263 teachers and 209 teaching pastors serving 472 schools with an enrollment of 30,320 students. By the synod’s 50th anniversary, there were 781 teachers and 894 teaching pastors serving 1,603 schools with an enrollment of 89,202 students. Within a generation, the Missourians had developed the largest Protestant school system in North America.

What accounted for the success of these schools? Timing was part of it, to be sure. The Saxon Lutherans had the good fortune of arriving in the St. Louis area at the beginning of a wave of German immigration that would see the population of the city grow twentyfold within the next 40 years. However, immigration patterns alone do not guarantee educational success. Earlier groups of Lutherans had established school systems in other parts of the country that did not survive. Most notably, in the late 18th and early 19th century, the Pennsylvania Lutherans developed a system of 240 schools at a time when, by some accounts, German immigrants to that state constituted a majority of the population. These schools went into steep decline at the very time when those of the Missouri Synod were experiencing rapid expansion. By 1860, there were only 28 Pennsylvanian Lutheran schools left.

A closer examination reveals some fundamental differences between the two.

Unlike earlier Lutheran schools in the United States, the schools of the early Missouri Synod held high academic and theological standards for their teachers. And contrary to popular misconceptions about frontier schools, they provided an exceptionally high quality of instruction. The synod put a great deal of effort into producing a pool of educators and clergy who were not only doctrinally unified but academically competent. It established high schools, colleges, teacher seminaries, and theological seminaries for this purpose.

The education received by the synod’s teachers and pastors exceeded that of most other Protestant clergy and state-educated teachers. For example, in the mid-19th century, the average American Methodist minister had achieved only an elementary level of education, whereas the typical Missouri Synod pastor had spent ten years at the college level and was thoroughly grounded in the liberal arts. This is significant when one considers that roughly half of the Lutheran schoolteachers were teaching pastors. Many children were taught by pastors who had mastered all three of the sacred languages and all areas of theology, were fluent in German and usually English, had studied logic and rhetoric, and conducted their office with a uniformity of teaching and practice that was virtually unparalleled in any other denomination.

The same held true for the synodically trained teachers. Many public-school teachers had no formal training at all. State “normal schools” generally required only a basic elementary education before admission and offered a teacher-training course that could be as short as one year. Classes centered on teaching practices and rudimentary educational psychology. By contrast, candidates for the Missouri Synod teachers’ seminary in Addison, Illinois, were required to have completed their elementary education as well as a full three years of preparatory training—a rough equivalent to the classical Lutheran gymnasium. Then, over the course of two years in the teachers’ seminary, they were exposed to almost all academic disciplines, studied in two languages, and had a comprehensive theological training. Thus the Lutheran teachers were equipped to offer an academically challenging education for even the brightest of students.

The academic integrity of these schools was surpassed only by their theological integrity. Teachers were expected to have an unflinching commitment to sound Lutheran doctrine. In the minds of the synod’s founders, if children were taught correctly—that is, if they were taught by orthodox teachers according to the precepts of classical Lutheran pedagogy—they would grow to be pious adults who would be able to articulate their Lutheran faith within the confines of their religious community and in the public sphere. Schools were to expose children only to the pure teachings of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. Their key text was Luther’s Small Catechism. The synodical constitution mandated that every child was to have the entire catechism memorized before he or she was confirmed, and synodical publications regularly reminded teachers of their obligation to see to it that this task was completed.

Special attention was given to ensuring that the methods used in the classroom were supportive of Lutheran theology. If contemporary pedagogical thought was opposed to orthodox Lutheran doctrine, Missourians were ready to reject it outright and employ a more harmonious pedagogy. For example, they took great pains to point out why the philosophies of leading educational thinkers such as Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (1746-1827), Friedrich Wilhelm August Fröbel (1782-1852), and Johann Friedrich Herbart (1776-1841) could not be used in their classrooms. A pedagogical theory that contradicted orthodox theology would, in the end, compromise the theological integrity of the classroom and defeat the purpose of its existence. This reflected a tradition in the Christian Church dating back to Saint Augustine, who held that the normative agent of education could only be theology. The leading educational theorists of the 18th and 19th centuries held a uniformly optimistic view of man and rejected Original Sin and the doctrine of a transcendent God revealed in Holy Scripture. Thus, no room could be given them in Lutheran pedagogy.

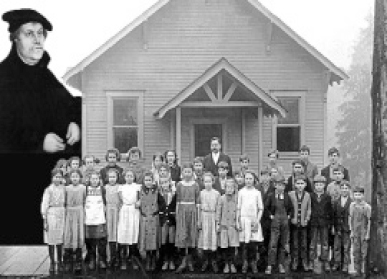

Instead, the American Lutherans looked to an earlier era for inspiration. In the 16th century, Martin Luther made some important contributions to the field of education. Among these was the understanding that one of the primary purposes of schools was to train Christian citizens who would maintain the temporal estate of the world and provide capable leaders of society.

For the 19th-century German Lutherans who had established themselves in a developing land, this vocational emphasis was especially relevant. From their point of view, God had brought them to a new land and provided them with the means to develop schools. They were therefore under a divine obligation to use the opportunity to help shape their new fatherland. Parents were repeatedly reminded of their obligation to educate their children so that they would serve their neighbor and be a blessing to the world. Echoing Luther, C.F.W. Walther, the first president of the young church body, wrote,

Since God has blessed many of our immigrant German fellow Christians materially in this our new fatherland, they recognize it to be their sacred duty to have their children not only trained sufficiently as Christians, but also to educate them as beneficial and useful members of society.

The second president of the Missouri Synod, F.C.D. Wyneken, also recognized that the Lutherans arrived in America at a critical juncture. The country needed faithful and thoughtful citizens and leaders who could make a positive contribution in all areas of private and civic life. If children could be properly educated—that is, if they were trained in the arts in an orthodox Lutheran environment—then they could exert a good influence on their communities as they entered into their vocations. As president of the synod, Wyneken reported to the 1857 convention that “The Lord has certainly designated our children in this country to be something more than mere hewers of wood and carriers of water for speculators.” Walther would reuse this line in the the synod’s magazine, Der Lutheraner:

If we German Lutherans in America do not wish forever to play the role of “hewers of wood and drawers of water” as is said of the Gibeonites in Canaan (Joshua 9:21), but to contribute our share toward the general welfare of our new fatherland by means of the special talents which God has bestowed on us . . . we must establish institutions above the level of our elementary schools . . . institutions that will equip our boys and young men for real proficiency in their occupations and business endeavours; for taking up any of the useful arts; for going into any of the professions; and for capable, useful service in all kinds of public and civic positions; so that they may generally acquit themselves as thoroughly educated men in any calling or station of life.

The Missouri Lutherans were German-speaking immigrants in an English-speaking land. This reality dictated their use of language in the classroom and determined that virtually every Missouri Synod school was bilingual.

There were good sociological reasons for this bilingualism, but the Missouri pedagogues tended to base their arguments for the retention of German on theological grounds. In the 19th century, virtually every orthodox Lutheran theological resource—dogmatics, catechisms, liturgies, hymnals, and devotional materials—was only available in German. The Missourians realized that if their children were not fluent in German, they would be cut off from these resources and, consequently, from the faith of their fathers. As a result, they insisted that classes, especially those dealing with Christian instruction, be conducted in German.

At the same time, these immigrants recognized that their children were growing up in an English-speaking country. It was therefore essential that they also be fluent in English. One early Missouri Lutheran educator, J.C.W. Lindemann, argued that if English were not taught to the children, they would be estranged from their new fatherland. Our children, he said, “are Americans and must dwell among Americans and must be with them and work with them and by God’s will must confess Christ and be salt with them.” English would enable them to participate in the national discourse of a developing country and to present the doctrines of the Evangelical Lutheran faith to a public that often misunderstood this German immigrant church. In addition to German history, music, and literature, children were taught American history, geography, and civics in order to integrate them further into mainstream society. The aim was to produce faithful, contributing citizens of both the spiritual and the secular realms. Instruction in German would aid them in remaining faithful to the Lutheran Church, while instruction in English would help make them faithful citizens of their new country.

The early Missouri Synod schools had their limitations. Student populations tended to be limited to those coming from within their own denominational boundaries. Teachers had a difficult time incorporating new and developing fields of study, such as science, into their curriculum. Nonetheless, students taught according to the traditional Lutheran pedagogy went on to take an active role in their communities, becoming leaders in both the commercial and political spheres, and demonstrating a devotion to their local Lutheran communities that went beyond mere church attendance.

Today, many liberal educational theorists insist that a classical Christian education retards a student’s autonomy and ability to think critically. The successes of the 19th-century Missouri Lutherans contradict such claims—provided that one’s definition of success includes several generations of students taught to live their lives as independent, thoughtful citizens capable of making positive contributions to church and community, as well as maintaining their faith.

Leave a Reply