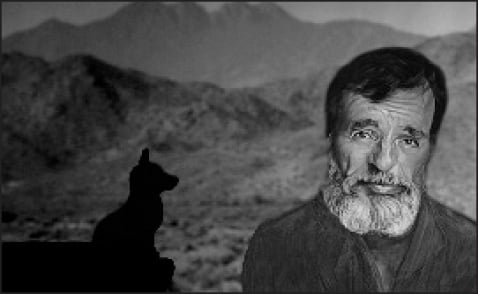

Edward Abbey never met a controversy he didn’t like.

Philosopher of the barroom and the open sky, champion of wilderness, critical gadfly, fierce advocate of personal liberty, Enemy of the State writ large: For 40-odd years, Ed roamed the American West, a region, he wrote, “robbed by the cattlemen, raped by the miners, insulted by the tourists.” As he traveled, he stirred up trouble by, among other things, poking ungentle and sometimes dangerous fun at cowboys, Indians, women, Mormons, Hispanics, and, above all, the agents of supposed economic progress—realtors, captains of industry, county supervisors, car dealers, developers. He was an equal-opportunity curmudgeon: Liberal and conservative alike felt his righteous wrath, which seemed to grow as the years piled on. And he liked the fight, wherever it found him or he found it. “Racial, sexual, cultural differences: forbidden ideas; we’re not supposed to think such things, much less say them out loud,” he grumbled in his journals, published in 1994 as Confessions of a Barbarian. “Yet it is fun to bring them up.”

He has been dead for nearly 20 years, felled by a bad pancreas on March 14, 1989, but the shaken-hornet’s-nest legacy of his stands intact. You can start a debate—and even a fistfight—anywhere from Missoula to Mexico City merely by mentioning his name.

I once went into a bar in Rock Springs, Wyoming, to grab a soda for the long ride to Jackson. Not long before, Abbey had given a speech at the University of Montana in which, among other things, he said,

Suppose you had to spend most of your working hours sitting on a horse, contemplating the hind end of a cow. How would that affect your imagination? Think what it does to the relatively simple mind of the average peasant boy, raised amid the bawling of calves and cows in the spatter of mud and the stink of sh-t.

Tough words in beef country, not guaranteed to win friends. A bullish cowboy at the bar took a look at my Arizona license plates, pulled himself up, and said, “You from Arizona? You know Abbey?” When I answered “Yes,” he said, “Get out.” I did.

Ed didn’t start out to be a scrapper, although he remarked that his Scots-Irish ancestry and upbringing in the Appalachian Mountains of Pennsylvania, both good ingredients for rebelliousness, predisposed him to disliking both authority and received wisdom. He was inclined to a kind of Thoreauvian, backwoods conservatism that prized self-reliance and self-education and disdained indolence, a credo that mistrusted any –cracy but meritocracy. He frequently ran into trouble when putting this ideal into practice, as when he was dressed down for not saluting an officer while in the military—perhaps ironically, as a military policeman—in the closing days of World War II. He remarked of this misadventure that he would salute a man anytime, but a uniform never. The Army, naturally enough, frowned on Abbey’s insistence that he be allowed to choose whom to salute, but he made out all right—and pressed the case in other arenas for the rest of his life.

He wanted to be remembered as a great writer, not as an activist, and he wrote a few novels—Black Sun, The Brave Cowboy, Fire on the Mountain—that earned him esteem as one of his generation’s most promising authors. But somewhere along the line, he decided that the West, to which he had moved in the early 1950’s after doing time in the Army and in New York City, had suffered enough at the hands of developers, logging firms, mines, corporate ranches, and other instruments of progress, which is so often regress. He began to speak out—no, to bellow out loud and long, arguing against the status quo in every medium he could find. Out this way, in many circles, he is still remembered more for his finely honed political rage than for his art.

I first laid eyes on Ed sometime in 1981, if memory serves, at a rally in Tucson against visiting Secretary of the Interior James Watt, the great satan of the environmental movement, who was then busily giving away the public domain to his wealthy patrons. Ed was the guest star of the unruly event, and his presence had been heavily advertised on posters and in ads in the alternative weekly. Ed seemed not to take that duty too seriously. He showed up bleary and much the worse for the wear after what appeared to have been a couple of weeks of nonstop drinking, mumbled a few semicoherent words about the evils of corporatism, growled, “God bless America—let’s save some of it,” and stumbled off into the night.

It turned out, Ed later told me, that he had in fact been drinking nonstop in the company of his “redneck radical” friends, planning and plotting the birth of Earth First!, the fringe environmental movement that, with Ed’s help and participation, would later give Watt and his successors so many headaches. The movement was inspired by Ed’s 1975 novel The Monkey Wrench Gang, in which a band of ecoradicals performed what he called “unauthorized maintenance on big yellow machines,” the Caterpillar tractors and earthmovers then as now busily blading over the commons. (Such equipment on private property, Ed insisted, was regrettable but off-limits.) Abbey called the book—a version of which is slated to make the silver screen sometime next year—a “comic extravaganza,” but many of his readers and followers took it more seriously than all that. Certainly, the FBI did: Ed’s file grew by several inches after the book appeared. He was pegged as a Marxist, but his politics were far from those of that other graybeard.

I got to know Ed better when, asked by a magazine editor to write an essay about Abbey’s politics, I decided to go straight to the source. Now, most writers at a certain stage of renown either guard their privacy jealously or slaver for still more publicity, but Ed did neither. Instead, he answered my questions courteously, pointed out flaws and overgeneralizations, and grumbled when my elegant theses about his views on anarchism, conservatism, and democracy got, well, too elegant. (He was right about that, and he would complain in his journals that the essay I eventually wrote placed “too much stress on my politics, no mention of the love and humor in my books”—about which, more in a minute.) For Ed, the story wasn’t himself or his politics, but the need for direct action against the land rapists and developers, for constant struggle against the enemies of the Bill of Rights (the Second Amendment as well as the First, for Ed delighted in twitting liberals with his lifetime membership in the National Rifle Association), and for rage against the machine.

We quickly agreed that the kinds of conversations we needed to have about such weighty matters would better take place in a bar or greasy spoon than in a library, and, over the next seven years, we met regularly to talk politics or books or the latest assault on the landscape. When we went for the first time to a tony, now-defunct fern bar in the unlikely heart of downtown Tucson, Ed walked through the swinging doors and bellowed, “Smells like lawyers in here!” It was a safe enough bet, given the bar’s proximity to the city’s courthouse and downtown’s countless law offices, and a dozen-odd carefully coiffed heads turned toward the door in reply. But the lawyers quickly turned back to their drinks. They had seen Abbey in action—everyone in Tucson, it seemed, had had an Abbey moment at one time or another—and they were not biting.

At our meetings, Ed, grinning wolfishly, would produce letters that he had written to such recipients as the New York Times, Ronald Reagan, the Nation, and Gloria Steinem, all of them raising pet peeves to the status of an ideology. “The fine art of making enemies,” he wrote in his journals. “I’ve become remarkably good at it.” Steinem was a favorite target, for he especially liked tweaking feminists, which may explain why he found so few women readers. He would be booed at readings throughout the 1980’s for insisting that he was a poet as well as a prose writer, then reciting scurrilous erotic lyrics bearing titles unsuited to citation in a family publication—and anathema to the politically watchful guardians of the academy, who grudgingly invited Ed to appear there and then professed to be shocked when he did what he did. No friends they of the First Amendment—or, for that matter, of the Second.

Abbey’s harshest moment in the spotlight came at about that time, when he began to publish a series of letters to the editors and essays on the subject of illegal immigration. Noting that the subject, like abortion and nuclear energy, was almost impossible to discuss unemotionally, Abbey insisted that the border between the United States and Mexico be sealed off with electric fences and patrolled by the military—strange talk for a self-professed anarchist. He did not help his case, which, he said, was based on environmental grounds (the United States was already overcrowded), by insisting that the American way of life had to be protected against the Mexican threat “to degrade and cheapen [it] downward to the Hispanic standard.” Cowboys are one thing, he found; politically well-organized ethnic groups, quite another. For the rest of his days, Abbey would be accused of racism, a damning charge against which he did not try to defend himself, but that gave him much pain, assured as he was that most people, as individuals, are merely fallen angels like himself, deserving of respect and courtesy. Lawyers, on the other hand . . .

Just before he died, Ed published The Fool’s Progress, what he called his “honest novel,” one loosely based on his own life. In its opening pages, Abbey’s alter ego, one Henry Lightcap, takes off from his nearly empty Tucson home (its contents having just been removed by a disgruntled spouse) after shooting his refrigerator, a hated symbol of civilization. Lightcap makes a winding journey by car to his boyhood home in the Appalachian Mountains of Pennsylvania, calling on old friends along the road, visiting reservations and out-of-the-way taverns, and reminiscing about the triumphs and failures of his life. Readers would be mistaken to view The Fool’s Progress as pure autobiography, but it looks deeply into his life and times and way of thinking. Abbey regarded it as one of his best books of fiction, and he was right to do so: It is full of wonderful moments, and the story stands as a mature rejoinder to Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, one of Ed’s favorite novels.

I had edited a 20th-anniversary reissue of Desert Solitaire, the book for which Ed is best known, and Ed asked me to read the manuscript of “Fool’s Progress” before he sent it off to the publisher. I did, and I wrote him that, while I thought the book very fine, I was disturbed by some of the humor, which I—no liberal—thought strayed into the very perception of racism that was causing him so much trouble. (“What’s the difference between Navajos and yogurt?” went one joke. “Yogurt is a living culture.”) I asked him whether he might reconsider portions of his book. Do you want, I asked him, to be explained away years from now like Ezra Pound? Ed wrote back and said that, of course, he would rethink the offending passages. Then, over the next few weeks, little white index cards began to appear in my mailbox, scrawled in blue ink in his crabbed hand, keyed to pages in the manuscript, announcing that he would keep this joke or that, that he would say whatever he wanted to about minorities “devoted to drugs, crime, spray paint, ward-heeling politics, cars and the monthly welfare check”—and to hell with what the East Coast liberal elite might say about him.

I was thus enlisted in the elite corps on the opposite coast, regardless of my own politics, for a while at least. Ed’s anger diminished, but, in the end, he kept his jokes, every last one of them. And I kept, and keep, my conviction that the book would have been better without them, less because of political sensitivities than because most of them were not funny.

Was Abbey a racist? Undoubtedly, at least after a fashion. Very few of his generation escaped being hit by that broad brush. Was he a paragon of virtue? No, and he never offered himself up as a model for emulation: He had his demons and his paradoxes, this man who despised cattle ranching but loved hamburgers, who railed against environmental despoliation but drove a gigantic Cadillac convertible, who preached devotion and loyalty to causes but had trouble remaining faithful to his wives, who scorned liberalism but contributed to the ACLU. He called himself a theoretical anarchist and a practical democrat, but Ed never bothered himself with developing a coherent politics apart from that most old-school of tenets: The individual trumps the collectivity, the collectivity is always suspect, freedom is the sine qua non of existence, the world is a fine place and worth fighting for. In all this, Ed was a kind of John Wayne, resolute and unwavering, but almost always smiling. Perhaps better put, he was political kin to another conservative and Arizonan, Barry Goldwater, who was perfectly consistent in his views and disinclined to compromise them, a far cry from the sort of glad-handism that wins elections these days.

The libraries of the world are full of little-visited books by grouches and complainers. Why do we continue to read Abbey? Well, for one thing, because, when he was on his game, he wrote truly and beautifully: There are few modern novels as heartfelt as Black Sun, no book about the Western landscape more evocative than Desert Solitaire. We continue to read him because no one else has so well captured the essential freedom and beauty of the West, and of America generally. We read him because he remained true to what he believed: for wilderness, for open space, for a world outside the city, for the individual.

The last time I saw Ed, we walked by a construction site on the way to a nearby burger joint. He pulled up a survey stake and tossed it out onto the road. “Earth First!” he grinned. A week or two later, he called to suggest that we have another meal. The night before we were to meet, a member of my family suffered a heart attack, and I called from the hospital to ask for a rain check. Sure, he said. A couple of days later, he died, his innards finally having given out after too many years of too much abuse. I now think that Ed knew he was about to leave the planet, and that he had wanted to say goodbye to an old friend who so often disagreed with him.

Ed now lies under 30-odd tons of volcanic scree under a cactus-studded escarpment somewhere in the desert of western Arizona, a battleground in the current war against illegal immigration. I think of him often, especially when I drive through cities such as Tucson and Phoenix and Los Angeles, grim hives that are busily chewing up the desert surrounding them, growing cancerously at the rate of an acre per hour, showing no signs of civilization and plenty of inclination toward the individual-crushing mind-set of the collectivity. The West Abbey loved is under assault every day. Much of it is gone, and things are getting worse.

But still, reading Abbey’s books, we take hope. And I suspect that, when the coyotes finally dig down to his bones thousands of years from now, the old controversialist and scrappy conservative will have had the last word.

Leave a Reply