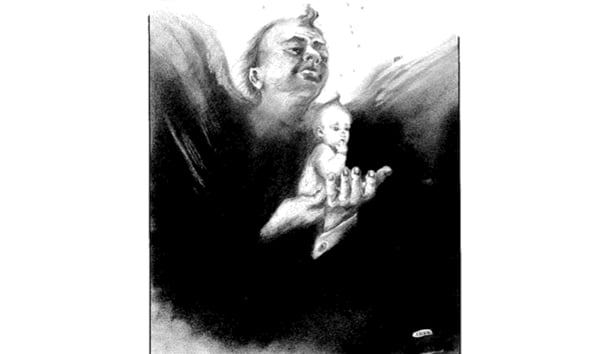

Participatory fatherhood. Shared parenting. The new American dad. By whatever name, the phenomenon has been two decades in the making, and we should have seen it coming. The self-centeredness of the 60’s ran headlong into the feminist harassment of the 70’s to create the Father of the 80’s: sensitive-and sensitive to his sensitivity; aware—and aware of his awareness; above all, involved—and very involved with his involvement. Having already coerced many insecure women into rejecting motherhood, feminism now has seduced a lot of narcissistic men into giving motherhood a try. Observing the result is like seeing a man with his fly open: alternately funny and embarrassing. Except, these men have unzipped on purpose. The new American father is the emotional flasher of our time.

These fathers demonstrate that to the totally self absorbed, no experience exists until they become a part of it. As if that weren’t irritating enough, their frequent response to discovering what everyone else already knows—in this case, that parents love their children—is to write books about their nondiscoveries.

Bob Greene is a writer who attempts, by his own account, “to capture the humanity of the people and events I am covering.” Unfortunately, his attempts don’t have much to do with his results; for his real skill is in making the interesting mundane and the mundane unbearable. His recent book, Good Morning, Merry Sunshine: A Father’s Journal of His Child’s First Year, reads like a Dick and Jane primer on first-time fatherhood. Bob is nervous during his wife’s delivery. Bob is worried when his baby cries. Bob is exhausted from all-night floorwalking. Bob is awed by his daughter’s tiny fingernails and thrilled by her first smile. Bob is concerned that fatherhood will make him less than the “pathologically ambitious person” he “defines” himself as. Bob has golden moments with his baby when it dawns

on him, that, geez, other parents must feel this way too. Bob is a bore.

Dan Greenburg, on the other hand, is a caricature. His book is called Confessions of a Pregnant Father, and, like Greene’s, it is written as a diary. Only, his diary begins not with his baby’s birth, but with its conception. Flashing away, he spares nothing. Not the detailed mechanics of procreation. Not the increasing breast size of his pregnant wife. Not the “exceedingly anxious” and “agonizing” weeks spent in his absurdly frantic search for a nanny—a search undertaken because “it had seemed to us that having a baby would be a lot more fun and permit us time to pursue our careers if we had a live-in person to assist with the baby.” In addition, he misses no opportunity to mention his “various shrinks,” his “twelve years of therapy,” his therapy group, his wife’s therapy group. (Indeed, the words, “therapy,” “breasts,” and “nanny” appear so often that they become somehow inseparable. Do nannies have breasts? Do nannies need therapy? Can a breast-feeding nanny have therapy) Being nothing if not an ace participatory father-to-be (check the book’s title), Greenburg discusses “our conception,” “our pregnancy,” and “our delivery” without a hint of irony, leaving one to conclude that either he needs a biology lesson or the National Enquirer has missed a pip of a story.

Greenburg is screamingly neurotic—which he finds not at all unusual. Isn’t everybody? His investigations of his fears and motivations, his feelings and reactions, are as automatic as walking and as frequent as breathing-and make less compelling reading than either. What is there to say, finally, about a man who, at the age of 47, writes with perfect pride and utter seriousness that he now has reached “the point in therapy and in life” where he can “confront” his “fears” and face being a father? Perhaps only this: Do therapists give refunds?

Caring, sharing (sticky, icky) men like Bob Greene and Dan Greenburg are not their own inventions. They are sim ply the latest wrong answer in a string of wrong questions about human relationships and personal responsibility.

Churning beneath the surface of the “new parenthood” is a palpable tension that manifests itself in a frenzy of anxious thought and activity, all of it designed to avoid the fact that the route of parenthood is exquisitely simple: Grown-up men and women who love each other and know what they believe in have children together, because children are one of the things they believe in. Believing also in themselves, these parents have no reason to fear their task. They raise their children through a combination of confidence and humility, with a balance of love and discipline, encouragement and restraints. They take their responsibilities as parents very seriously, while trying not to take themselves too seriously. They do their duty naturally (if sometimes wearily), the willing acceptance of duty being one more thing they believe in. In the process, the parents gain wisdom. What the children gain is character, a prerequisite to wisdom. Simple. But not easy. For the going can get rough, and no detours are allowed. Which is another fact the new parenthood exists to avoid.

Successful avoidance is accomplished by beating your brains out to find, and paying through the nose for, nannies and day care—which are necessary because without them, how can you pursue your career? And if you can’t pursue your career, how can you become a fully realized human being? And in the end, isn’t a non-fully humanly realized parent a bad example for a child? Besides, how else could you pay for the nannies and day care?

After that, you can spend your remaining time, energy, and money on parent discussion groups and infant play groups and parent/infant play groups and, most important, infant development classes. After all, it’s a tough world out there, and doesn’t a kid who can count to 10 before he can talk just naturally have a leg up on the competition?

Finally, you can become your child’s best friend, because friends are loose and fun, and friends don’t upset children with the messy business of teaching them how to live. And everyone knows that children shouldn’t be upset. Do you like being upset?

These parents display a conceit born of self-indulgence and a desperation born of insecurity. While children are the cause of neither, they inevitably become an excuse for the conceit, an object of the desperation, and the unfortunate victims of both. The authors discussed above both write that fear was their overriding reaction to the prospect of becoming fathers. Predictably, their fear centered on the question of how their lives would change. You see, they liked their lives the way they were. Except that they actually didn’t like their lives, because something was missing. What was missing was a child, the child they wanted in order to change the lives they didn’t really want to change. Get it? Neither do they.

This knot of tortuous thinking is the product of minds utterly unaccustomed to handling two demands at once. To one who has thought only and always of himself and loved every minute of it, the prospect of someone else moving in on the fun forever can’t be anything but frightening. This combination of vanity and fear serves to shift the focus of parenthood from the question of who we are for our children to what we do about them and avoid doing to them. That accomplished, the agenda is easy. What we do about them is provide endless structured “learning activities.” What we don’t do to them is engage in confrontation. If this agenda carries the risk of producing, in the first instance, compulsive little “achievers” and, in the second instance, tiny social barbarians, who has the time or the nerve to think about it?

When forced back to the question of who they are for their children, when the real fear begins to creep up, fathers like Dan Greenburg reassure themselves with the pathetic but well-chosen delusion that having children is “a great way to feel good about yourself” and a lot of “help in growing up.” (Isn’t that where we were supposed to have started?) By making their own development the main theme of fatherhood, these men can skirt, for a while, those rough spots where the real business of parenthood takes place.

What they are hoping to evade is this: the crux of parenthood is emotional grunt work. It’s: No, you can’t have a third cookie; no, you may not interrupt others while they’re talking; no, you cannot throw toys when you’re angry (yes to anger, no to throwing; and that’s even more work). It is knowing that any child, at any moment, is capable of disproving any theory of child-raising that ever existed. And it is understanding during this process that while parents won’t be feeling especially realized, their children will be learning something that cannot be found in a shape-recognition drill.

A little later things change to: No, you may not: have a Moped, skip your homework, see Porky’s, stay up till midnight, call your sister/brother a jerk, or get a tattoo, even if Jennifer-Jason-Amy-Josh has been granted such privileges since birth, even if your teacher says it’s okay, even if you want to trade me in for a better model-and by the way, I wouldn’t trade you for the world. It is the willingness to be, from time to time, very unpopular with those you love the most because you love them the most.

Later still, it’s trying to explain, at the same time, the connection between love and sex and the difference between love and sex. It’s teaching that effort is sometimes its own reward (a tough one, but it connects up later with duty-as-its-own reward). It is trying to encourage without nagging, nag without bullying. It’s taking your opportunities where you find them by listening when you feel like talking and talking when you feel like going to bed. It is getting Off and On—off yourself and on the job—time and again, so that somewhere down the line your children will know, among other things, who to be for their own children.

We are not talking here about the popular concepts of “quality time” and “shared experiences” (although it is quality time, and they are shared experiences). We’re not talking about parenthood in the trenches. It is not, by any means, where all of parenthood takes place; but it’s where some of it must take place.

Not for the Dad of the 80’s, however. His idea of trench work is changing diapers, a job which, because his father refused to do it, automatically qualifies him for the Unthreatened Masculinity award. Yesterday’s relentless self explorers became today’s enlightened fathers when and because they realized that as enlightened fathers they could remain relentless self-explorers-and appear responsible yet-sensitive in the bargain. Jackpot. And where do their children fit in? Well, they get to be little sidekicks on dad’s wondrous journey of self-discovery. Look! Over here! I’m feeling good about myself!

Past the surface, it’s not at all funny, of course. The notion that children can be used to help their parents grow up is perverse and offensive and dangerous. But you wouldn’t know it by Today’s Dad. He’s found himself an Image; he’s found himself a Role. He’s proud as punch and bursting to talk. Me, I’m damned if I’ll listen.

Leave a Reply