At 0825 on 20 November 1943, the first of six waves of Marines left the line of departure and headed for the beach on Betio Island, the principal objective for the United States in the Tarawa Atoll. At 4,000 yards out, shells from Japanese artillery pieces started splashing around the amtracs carrying the Marines. At 2,000 yards, mortars joined in. At 1,000 yards, machine guns opened up. The sound was deafening. Shells were exploding everywhere, and millions of metal fragments filled the air. Amtracs suffered direct hits and exploded in balls of flame and smoke. At 800 yards, the surviving amtracs reached a shallow reef, crawled over it, and began the final run to shore. The murderous fire continued all the way to the beach. There were only enough amtracs for the first three waves of Marines. The next three waves came in Higgins boats.

There was nothing intrinsically wrong with the landing craft designed by an old Marine, Andrew Jackson Higgins, but the craft lacked treads and could not crawl over obstacles like the amtrac. This should have been no problem, but the tides and the depth of Betio’s reef had been miscalculated. At 800 yards out, the Higgins boats hit the reef and ground to a halt on the sharp coral. The Marines could do nothing but leap over the sides of the foundering boats and begin wading towards the shore. Shells exploded all around them, throwing columns of water—and the bodies of Marines—high into the air. Machine-gun fire cut down others. The death toll was enormous.

Lt. Cdr. Robert MacPherson, a Navy pilot in a scout plane high overhead, looked down on the Marines wading ashore and later recorded: “The water seemed never clear of tiny men, their rifles held over their heads, slowly wading beachward. . . . They kept falling, falling, falling . . . singly, in groups, and in rows. I wanted to cry.”

No Marine ever took a step backward. As a war correspondent with the fifth wave, Robert Sherrod, said: The Marines were “calm, even disdainful of death . . . black dots of men, holding their weapons high above their heads, moving at a snail’s pace, never faltering.”

Seventy-six hours later, the Marines declared Betio (or Tarawa, as we tend to call it) secure. In those three days, 1,100 Marines were killed and 2,300 wounded —3,400 casualties for an island two miles long and less than half a mile wide.

Those Marines did not wade ashore and claw their way across the island for some abstract set of principles enunciated in founding documents—at least, not directly. Those Marines exhibited uncommon valor because they were defending something far more valuable—far more atavistic and inspiring—far more primal. Those Marines were defending their tribe—a tribe united by race, language, culture, and religion.

Those Tarawa veterans alive today must wonder what their sacrifice accomplished in the long run. The Los Angeles that I grew up in—in the years immediately following World War II—has been transformed since the 1970’s into a dumping ground for the peoples of the Third World. When I went through the Los Angeles city schools, they were 85 percent white. Now they are 85 percent non-white. English, spoken by virtually all students as a first language in the 1940’s and 50’s, is now a second language for the majority of students in the elementary schools. Although difficult to document, there is evidence to suggest that nearly half of the elementary-school students are the children of illegal immigrants. I do not think this is what the Marines fought for.

Buddhist shrines, Muslim mosques, and Hindu temples dot the city and its suburbs. In the greater Los Angeles area, there are 600,000 Buddhists—ten times the number of Episcopalians —and the largest Buddhist temple outside of Asia. There are more than 200,000 Muslims—triple the number of Presbyterians—and 70 mosques. There are some 130,000 Hindus—more than double the number of Methodists—and a dozen Hindu temples. The area is now home to 100,000 adherents of Santeria, an Afro-Caribbean cult that practices animal sacrifice and voodoo-like rituals. I do not think this is what the Marines spilled their blood for.

The destruction of the American tribe is proceeding at a rapid rate in Los Angeles. Race, language, culture, and religion are retreating under a withering fire. It may be happening in your city—or it soon will. Welcome to non-white, non-English speaking, non-Western, and non-Christian America. Instrumental in this destruction is Hollywood—the motion picture and television industry. To the industry, white and Christian is bad. White, Christian, and male is very bad. White, Christian, male, and conservative is abominable.

Do not underestimate the power of the industry. A recent survey found that only 12 percent of American teenagers can name Abraham Lincoln’s hometown, but 74 percent can name the town where cartoon character Bart Simpson lives. Only 41 percent can name the three branches of government, but 90 percent know that Leonardo DiCaprio is the star of the movie Titanic. Only two percent can name the chief justice of the United States Supreme Court, but 95 percent can name the actor who played the Fresh Prince of Bel-Air on television. Only two percent know that James Madison is considered the father of the Constitution, but 90 percent know that Tim Allen is the star of Home Improvement. Most astounding of all, perhaps, only 21 percent know that the United States Senate has 100 members, but 75 percent know that 90210 is the ZIP code for Beverly Hills.

This last point frightens me most of all. Isn’t figuring the number of senators simple deduction? It all goes to show what watching five hours a day of TV—the teenage average—can do for our youth.

Now, can you imagine asking these same teenagers about Tarawa? I suspect fewer than one percent could even identify it. Would the names William Deane Hawkins, William Bordelon, Alexander Bonnyman, or David Shoup mean anything to them? Those four Marines won the Medal of Honor for taking that speck of real estate in the Pacific. Three of them died doing it.

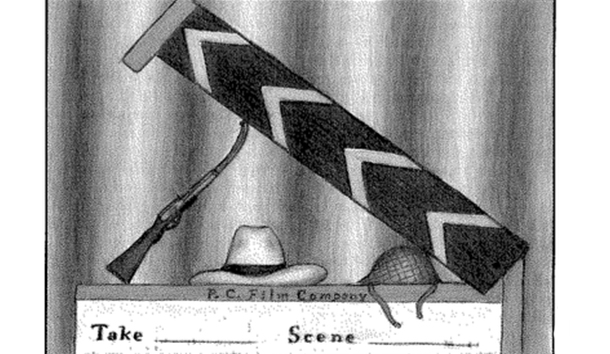

Hollywood used to do a fair job with such subjects—and we were the good guys. Everyone knew about Jimmy Doolittle’s raid on japan—Thirty Seconds Over Tokyo; and the Marines destroying the vaunted Japanese jungle fighters on that stinking, rotting, malarial-infested island of Guadalcanal—Guadalcanal Diary. We all knew about the five Sullivan brothers fighting and dying in the Naval Battle of Guadalcanal—The Fighting Sullivans; Claire Chennault and his P-40 pilots performing heroic feats in China and Burma—The Flying Tigers; the 8th Air Force in death-defying missions in the skies over Germany—Twelve O’clock High; Anthony McAulliffe replying “Nuts!” to the German demand for the surrender of the 101st Airborne at Bastogne—an event in Battleground and in several other movies, including Patton; the Marines raising the flag on Mt. Suribachi—The Sands of Iwo Jima; and little Audie Murphy leaving hundreds of enemy dead in his wake—To Hell and Back.

Movies portraying white males in heroic roles in actual historical events—unless somehow they involve a politically correct theme—are nearly non-existent today. A good friend of mine, Col. Ed Ramsey, went into the bush when the American surrender occurred at Bataan. Ramsey was a young lieutenant in the 26th Cavalry at the time and joined a handful of other American officers who decided that they would slip through the lines and organize Filipinos for guerrilla warfare against the Japanese invaders.

Eventually, Ed Ramsey commanded 40,000 guerrillas and became Japanese Lt. Gen. Hideo Baba’s most-wanted man. Gen. Baba offered the equivalent of a million dollars in today’s money for information on the whereabouts of Ramsey, but no Filipino, including those captured and tortured to death by the Japanese, ever betrayed him. To the Filipinos, Ramsey was their leader, their hero.

Ramsey spent three years in the jungles of the Philippines and wreaked havoc on the Japanese. He came close to death on several occasions. What he did in those three years is mindboggling. By the time MacArthur returned, Ramsey was terribly debilitated from wounds, disease, and malnutrition. He had lost nearly 40 percent of his body weight and weighed only a hundred pounds, but the skeletal Ramsey, by then a major, managed to stand at attention while MacArthur promoted him to lieutenant colonel and pinned medals on his chest. Ramsey spent the next two years in VA hospitals recovering.

You would think that Ed Ramsey’s story would make a great book—and you would be right. In 1991, after years and years of writing and stopping, putting the project aside, and then starting again, Lt. Ramsey’s War was published. I was at the Filipino consulate in Los Angeles for the official launching of the book. The Filipino consulate was an appropriate venue because Ramsey’s decorations from the Philippine government are second only to MacArthur’s. It was an emotionally charged and poignant event.

Plenty of big brass from the United States were there, but most telling were the dozens of Filipino veterans—men who had served under Ramsey—who managed to attend. With tears in their eyes, their voices too choked with emotion to speak, and many of them on unsteady legs, they stepped up to their beloved commander and embraced him. Some of them almost collapsed.

You would think that Ed Ramsey’s story would make a great movie—and you would be right. A major studio bought the rights to the book and paid big bucks to two screenwriters to prepare a script. A big-name director signed on to the project. Famous actors were interested in the various roles. Everything was good-to-go. Then there was a shakeup, totally unrelated to this particular project, of studio executives. All projects were reviewed. One of the new executives looked at Lt. Ramsey’s War and said: “Impossible. We can’t have a white man leading all those people of color.”

Well, the fact remains that Ed Ramsey did lead 40,000 Filipinos, and he helped deliver the islands from the Japanese, “people of color” who managed to kill a million Filipinos, many through the most diabolical tortures imaginable. Ed Ramsey is an American hero and a hero to the Filipinos.

The movie project has been on hold now for more than a year, but there may eventually be a happy ending to all this. Since the success of Saving Private Ryan, the studio has reconsidered the project. The smell of big money has evidently caused the politically correct executive to cast aside his fashionable principles. In addition, another studio has expressed interest in acquiring rights to the project.

Ed Ramsey, despite major heart surgery, is still going strong at 81 years old. He gives guest lectures in my World War II class, and the students cannot believe that he is the hero they have been reading about, standing in front of them in the flesh. The young co-eds are especially taken by him. They think he looks good. He thinks they look good, too. The colonel, the Old Man, is still amazingly robust. I just hope he lives to see himself on the silver screen.

For the last ten years, I have dealt with Hollywood in a variety of capacities—as a consultant and technical advisor for a television series, as a consultant for various film and television projects, and as an interview subject for documentaries. The push for political correctness or, perhaps more accurately, cultural Marxism is pandemic. However, I have found politically incorrect individuals in the business.

In 1991, I was brought on board the television series The Young Riders by David Gerber, the chairman and CEO of MGM Television at the time. Gerber hired me to make the series more authentic and historically accurate. He thought the producer and the writers had taken far too many liberties with the plots and characters; the series was supposed to be based on the Pony Express and on actual riders.

I immediately hit it off with Gerber. He was a straight-talking, no-nonsense, down-to-earth guy who had worked his way up in the business from the mailroom. He also was amazingly well read and had a solid grounding in history. He had read extensively not only in popular historical literature but also in scholarly historical literature. We had much to talk about. I also got along well with Gerber’s assistant, a sharp young executive with loads of energy, talent, and integrity.

Not so with the producer of the series. He thought of himself as a creative genius and looked upon me as a threat to his works of art. Furthermore, I was out of the chain of command, and this drove him nuts. I reported to Gerber. The producer could not attempt the normal game of intimidation that is very much a part of Hollywood. I learned that Hollywood is very hierarchically structured and that intimidation and even humiliation of subordinates is de rigueur for some of those in the business.

Part of this is the fault of the subordinates themselves, many of whom are among the most sycophantic people I have ever come across. These same sycophants turn right around and treat the people below them like dirt. Now, of course, not everybody fits these descriptions. Nonetheless, there seems to be a greatly disproportionate number of such types in Hollywood. Some of it, I think, has to do with the enormous money to be made in the business. There are large carrots dangled in front of everyone, and the attempt to please a superior takes precedence over principles, morals, and truth-telling.

Large carrots? The producer of the The Young Riders was making $30,000 a week. I can only imagine what he thought when he looked out of the window of his plush office in the MGM building and saw me driving up each week in my 1971 VW bug with rusted surf racks on the top, knowing that I was there to tell him what changes he should make in the script. I am told he threw fits each week after I left. As you might suspect, I did not ingratiate myself with a producer who made more money every two weeks than I made in a year. I tried to be tactful and polite, but I had to do the job that I was brought aboard to do. I simply gave the producer and the writers the straight scoop.

Most of the writers seemed far less driven by a politically correct agenda than the producer, although they were eager to please the producer and get their teleplays on the air. Most of them accepted the liberal cliches of the university campus and of Hollywood and generally wrote that way, but it was my impression that they seemed more concerned with working and picking up a paycheck. They were well paid, they worked hard, and they were skilled at their craft. Several actually seemed eager to be made aware of historical inaccuracies and misrepresentations and tried to tell a good story honestly.

I worked on some 50 scripts—44 of them aired as episodes of The Young Riders—before the series went off the air. A few examples from a few of the scripts should give you an idea of what the politically correct of Hollywood want us to think.

There were no black Pony Express riders; however, in the interests of “urban demographics”—Hollywood’s code phrase for blacks—it was decided that one of the principal characters would be black. I suggested that he be a wrangler at the station, but that would not do. He would be one of the riders. He was named Noah, and he was just like the white riders except—he was perfect. After some time, I came to realize that Noah was not merely an Old Testament patriarch come to ride for the Pony Express: He was God.

It was also decided that there should be some Mexicans in the show. A Spanish mission suddenly appeared in Wyoming, near the home station for our riders. That the nearest Spanish mission was actually in the upper Rio Grande Valley, 600 miles to the south, did not seem to matter. Now we could have Mexican heroes. At least the priest who ran the Spanish mission was Father Reilly.

One of our riders was Wild Bill Hickok. Although he never was a rider for the Pony Express, he did work as a teamster for Russell, Majors and Waddell, the firm that created the Pony Express. Making him a rider and a dozen other historically inaccurate things that were done with him in the series are probably forgivable—dramatic license. One script, however, had him making anti-gun statements—something to the effect that he hated the darn things but was forced to use them and it would really be best if nobody had them.

The real Hickok was fascinated with guns from childhood. He got his own revolver at the age of 12 and practiced with it constantly. He was a deadeye and proud of it. As an adult, he carried two Colt Navy revolvers and two derringers. He had a collection of guns that included not only pistols but rifles and shotguns as well. He took target practice daily and cleaned and reloaded his weapons every night.

Jesse James was also in for some revisionism. Although he never had anything to do with the Pony Express, he appears in the series as a teenage boy working at the station. Jesse has all sorts of modern angst and talks and cries openly about it. In one scene he sobs, the tears flow, and he purges his soul. This modem angst-ridden crybaby would certainly come as a surprise to those who knew the real Jesse. His family always remarked that, even as a little boy, he was tough as nails. The last time his mother could remember Jesse crying was when he was three years old and his father left home for the goldfields of California.

In the series, Jesse also has to be taught the use of firearms. He is portrayed as very nervous around guns, and in a critical situation he freezes and is unable to pull the trigger. The real Jesse was an accomplished hunter and tracker and an expert marksman by his early teens. By the time he turned 17, he was a Confederate guerrilla riding with Bloody Bill Anderson. As Anderson described young Jesse: “Not to have any beard, he is the keenest and cleanest fighter in the command.”

I probably do not have to tell you that our Indians were always perfect. They never killed women or children or innocent men, nor did they scalp or mutilate their victims. They treated their women honorably and respectfully. Only whites perpetrated atrocities and abused women. Story lines that had Indians chasing Pony Express riders were rejected out of hand, although there are several true stories of lone Pony Express riders being chased by dozens of Indians, suffering terrible wounds, and yet miraculously escaping. Great stuff, but not the stuff The Young Riders was made of.

Recently, I served as a consultant for a major studio doing an historical project on California. Again, the political correctness was evident on every page of the script. Nearly every scene featured “people of color.” If whites were to be shown, they had to be part of—in the studio’s words—an “ethnically diverse” group. For example, four figures represented the miners of a gold town in California. One was black, one was Mexican, one was Chinese, and one was white: perfect balance and perfect nonsense.

I doubt it will make much difference, but in my notes for the studio I provided the federal census for Bodie, about as typical a mining town as one could find. The census counted some 5,400 people in the town. Of these, 92 percent were white, 6 percent Chinese, 1.9 percent Mexican, and 0.3 percent black. I could find no mining town where blacks constituted more than one-half of one percent of the population. So, yes, blacks were in the gold camps, but in numbers so small as to be almost invisible.

The Chinese were the only significant non-white group, but even they accounted for only six percent of the population in Bodie and were never much more than that in any camp. No matter: The gold camps will be portrayed as “ethnically diverse,” meaning one-quarter black, one-quarter Mexican, onequarter Chinese, and one-quarter white.

When it comes to the mining camps of the 19th-century West, the term “ethnically diverse” should really be reserved for the different kinds of whites. In Bodie, half of the 5,400 residents were foreign-born whites. Some 850 had been bom in Ireland; 750 in Canada; 550 in England, Cornwall, or Wales; 250 in Germany; 120 in Scotland; 80 in France; and 60 in Sweden, Denmark, or Norway.

Then, of course, there were the 2,400 native-born whites from various sections of the country. This is what diversity meant in the mining camps of the Old West: Irishmen and Scots; Cornishmen, Welshmen, and Englishmen; Germans and Scandinavians; Frenchmen; New England Yankees; big city New Yorkers; Virginia cavaliers; Midwestern farmers; Texas Comanche-fighters; and others from all points between.

Whites simply do not seem to count anymore when it comes to such projects. To portray the struggles and achievements of whites just will not do. Yet California has been more than 90 percent white for most of its history as a state, and, as a result, most of those who have struggled and achieved have been white.

I was surprised to see in this latest project that even the Okies, except for one brief scene, were ignored. At one time, they had some status as an oppressed victim group and, therefore, were worthy of a sympathetic portrayal, as in John Ford’s epic. Grapes ofWrath. Today, being white, they get almost no portrayal at all, yet they had a profound effect on the state of California and had it far, far rougher than any immigrants today.

Between 1920 and 1950, some 1.2 million people from the greater Dust Bowl region arrived in California, most of them Okies, Arkies, and Texans. Many areas of the state were transformed. By 1950, Dust Bowl folk constituted 12 percent of the state’s population. In the San Joaquin Valley, they were 22 percent of the population. Even in Los Angeles, they were more than ten percent of the population.

They were instantly identifiable by their dress, accents, language, country-western music, and evangelical Protestantism. They were down-home folk, proud, conscious of their separate identity, ready and willing to fight, and tough. It is no longer fashionable or politically correct to mention them, though, because they were white and their necks were burned a deep red after a day in the fields.

If network television and the major studios are mostly controlled by the industry’s prevailing ideology of political correctness, the cable channels offer some hope. I have been an interview subject for some 40 documentaries, including two dozen episodes of The Real West. Most of the producers I have worked with have been determined to tell the story straight. They have had real integrity and produced a finished product in which I was proud to appear.

The Real West first aired on A&E several years ago and quickly became the most popular series in the channel’s history. I do not know if the series still holds that claim to fame, but it is regularly rerun now on the History Channel. Middle America, when given the opportunity, consumes real history with a voracious appetite. I cannot tell you the number of people from every region in the country who have written me over the years, praising the The Real West and thanking me for my work in it.

Actually, real thanks should go to Greystone Communications, the producer of the series, and to the individual producers of each episode. I just hope that those producers, as they move up to bigger and bigger projects, do not compromise their integrity for the megabuck carrot of Hollywood.

Of course, I have also worked with documentary producers who have had politically correct agendas. One such company, which was doing a series for Ted Turner, filmed me for more than two hours at the Autry Museum of Western Heritage. I was not far into the interview before I realized that I wasn’t saying what the producers wanted to hear. When the documentary aired, I had a very small role in it. What was left of my interview had been edited to render my comments innocuous and generally compatible with the producers’ agenda.

I shall continue to do my best to tell it straight, but I shall also keep my powder dry. The day may come when it will be necessary to take America back. Do not let the Marines’ sacrifice at Tarawa, or the sacrifice of Americans at any other beachhead or field of battle, be in vain.

Leave a Reply