A reporter once asked Tyrone Power if he thought his next movie would be a hit. “That depends,” Power replied, pointing to his face, “on how many close-ups of this make the final cut.”

Another case of celebrity vanity? Perhaps, but I prefer to think Power was on to something essential about the nature of film. Take a face, virtually any face, and project it seven-feet high by five-wide on a theater screen, and you instantly confer iconic power on its owner, however ordinary looking—and Power’s puss was far from ordinary. But consider a couple of less camera-friendly mugs. No one could have predicted that the face of Robert Mitchum or of Betty Davis would become instantly recognizable staples of our popular culture, but both did. Why? Their indelible close-ups. When it came to the otherworldly beauty of Ava Gardner and Cary Grant, the iconic effect was utterly devastating. Which is especially remarkable, since neither Gardner nor Grant would likely have had a chance in theater. Their thespian range was, to be charitable, limited. On-screen in close-up, however, they were irresistible.

The Tyrone Power anecdote came back to me unsummoned as I began writing on the politics of film. I had been jotting down the usual thoughts that arise whenever film and politics are mentioned in the same breath. Film is a mass medium; it caters to the mass audience. Screenwriters and directors naturally pander to the common man with the usual assortment of left-leaning bromides: Feelings provide a better guide than intellect; wealth corrupts, poverty ennobles; spontaneity trumps planning every time; and, oh yeah, those who belittle the Clintons and admire Eisenhower and Reagan should be taken into the street and shot.

All true, of course, but hardly news. But then Power’s face appeared before my mind’s eye—in close-up, at that. It set me thinking. What does the close-up mean? Once raised, the question seemed neither odd nor difficult. The answer was obvious. The face filmed in close-up is more than an object of aesthetic contemplation: It is a political statement. Power’s face, Davis’s face, any face shown that large on a screen impresses us with its unique personal being. Marshall McLuhan famously told us “the medium is the message.” The message of the close-up is that individualism must be honored as the inviolable basis of all human truth and beauty. A screenwriter or director might be a communist or fascist or syndicalist; he might fervently believe it right to sacrifice the individual to the needs of the collective; he may want to propagandize in favor of Lenin, Hitler, or a certain former first lady. It doesn’t matter. What shines so incandescently from the screen is Power’s close-up. Or Streep’s, or Redford’s, or Clooney’s, all highly specific individuals both in the characters they play and in their own persons. The force of the close-up resists any attempt to reduce these performers and their roles to class identities—the worker, the bourgeois, the aristocrat—no matter how politically expedient such a reduction would be.

When they wish to, poets and novelists can emphasize the group over the individual. Think of Leo Tolstoy or John Dos Passos. To a lesser degree, so can playwrights, Anton Chekhov and Bertolt Brecht being obvious examples. Film, however, finds it exceedingly difficult to focus on the village at the expense of the wife, the husband, the child. Or the barber, for that matter.

Movies, despite their content, tend to be formally conservative. To the degree that they use close-ups in their story-telling, they celebrate the individual and the individual’s rights. Were there any films that didn’t rely on the close-up? I could think of quite a few that emphasized people in groups and formations—they were often those produced in totalitarian states, but, even at that, they had plenty of close-ups. The Soviet propaganda film Battleship Potemkin (1925) and the Nazi Triumph of the Will (1934) were made by directors ideologically committed to celebrating the people rather than individuals, but they couldn’t do without close-ups—the first, to represent the valiant masses; the second, the valiant leaders. There have been experimental attempts to minimize close-ups—Peter Greenaway’s Prospero’s Books comes hideously to mind—but they inevitably seem strained and awkward. The truth is that directors find close-ups all but indispensable, and, wherever close-ups appear, they undermine attempts to replace the individual protagonist with an heroic collective.

Depending on their politics, directors have found that the close-up’s iconic power either hindered or advanced their purposes. Those on the left have struggled to make the close-up fit in with their socialist agenda, while those on the right have enlisted the close-up almost as if it were integral to their traditional argument that government governs best when it governs least. This is unmistakable when we consider films with pronounced political objectives, especially the classics.

Take the mother of all propaganda films, Battleship Potemkin, made by the ingenious Soviet director Sergei Eisenstein. Joseph Stalin himself commissioned Eisenstein to celebrate the Bolshevik Revolution on celluloid. The result has been described as a live-action political cartoon, and so it is, albeit one made with dazzling cinematic craft.

Following Marxist doctrine, Eisenstein insisted the working class would be the hero of his film. He chose for his story an historical event, the 1905 Potemkin mutiny. His movie dramatizes how the ship’s abused crew rose up against their middle-class officers who had, allegedly, been forcing them to serve as though they were slave laborers on a diet of rotting food. Their successful rebellion sparks a revolutionary awakening among the working-class citizens of Odessa, the port into which they sail once gaining control of the ship. The people are then shown sending aid to the ship’s crew until, by order of the tsar, the Cossacks march on them, firing at will into the innocent crowd. The citizens flee wildly from the onslaught down the harbor’s steps, in a scene that has become one of the most praised and quoted in cinematic history. (Brian De Palma paid amusing homage to it in The Untouchables.) Judged aesthetically, the sequence deserves its kudos; judged historically, it is about as factual as the flying monkey attack Dorothy suffers in the Wizard of Oz. The Cossacks were trying to quell a murderous riot, and, only after several days did they resort to shooting. But this was nothing like the sustained attack Eisenstein staged on the Odessa Steps.

Eisenstein’s purpose was to justify the Bolsheviks’ bloody revolution, and that meant truth was secondary to ideology. Despite his artistry as a filmmaker, however, he fails to deliver on his intention. We are supposed to be witnessing class struggle, but what one recalls of the film are the faces in close-up: a sneering officer pushing cowed sailors about; a thick-set, walrus-mustached seaman (astonishingly Stalin-like) encouraging his crewmates to rise up; an old lady pleading with the exterminating Cossacks only to be slashed with a saber across her face. All these images speak more of the pathos of individuals than of classes. These people are irreducibly themselves. The cant leftist formula say that the personal is the political. In film, it is the opposite. The close-up makes the political personal. As a result, the medium tends to subvert the ideologue’s attempt to collectivize humanity.

Next, consider the case of Michael Curtiz, a Hungarian émigré who, at Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s request, directed two pro-war propaganda films in 1942 and 1943, Casablanca and Mission to Moscow. Neither achieves its aim.

Mission is an embarrassingly crude piece of work based on former Amb. Joseph E. Davies’ equally fatuous book. Both text and film are ludicrous efforts to explain why it was America’s duty to support the Soviet Union in its hour of need. Still, the film is not without its entertaining moments. At one point, Davies meets Stalin, who looks for all the world like everyone’s dewy-eyed granduncle. Puffing thoughtfully on his meerschaum, Uncle Joe explains to Davies why he made a nonaggression pact with Hitler. It seems he had no choice. No one was willing to come to Mother Russia’s aid, and he had to placate the Hunnish hordes. Needless to say, Mission’s mission was to convince the American populace that they had no choice, either. Americans had to go kill the krauts, or else the good commies would be up the Volga. This movie is too silly to dwell on except to say that the close-up rule prevails once again. What one remembers most is Stalin’s face filling the screen. As played with mannered sincerity by Manart Kippen, he appears to be a man you would have investigated before you’d trust him to mind your pet turtle.

Casablanca is a different matter. It has long been regarded as an American classic. Its mix of romantic longing and bittersweet resignation against a backdrop of international intrigue continues to move viewers today, although I doubt they pay much attention to the story’s propaganda payload. Humphrey Bogart plays Rick, the disillusioned cynic determined to sit out the war in Casablanca. He cultivates a studied neutrality in all things political until his former lover, Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), shows up at his nightclub-cum-gambling-den one evening. She is nearly as dewy-eyed as Uncle Joe in Mission. What’s more, she is delicately wrapped in a velvety soft focus you can’t buy at Bergdoff Goodman’s cosmetic counter. And then the soundtrack plays “As Time Goes By,” courtesy of the wonderful Dooley Wilson. Rick’s neutrality naturally founders. Sure, back in Paris, Ilsa had forgotten to tell him she had been widowed by a man in the Resistance. And, yeah, she had ditched Rick at the Gare du Nord when her hubby suddenly showed up in the pink once more. Nevertheless, she only has to look at Rick with those moist eyes and parted lips, and he is back on duty. He will shoot Nazis by the dozen to help Ilsa and her husband escape Casablanca and return to their work in the Resistance.

I wonder how many in 1942 suspected that Curtiz was feeding them FDR’s—and, by extension, Moscow’s—line. Bogart must have seemed too honorable, and Bergman, too beautiful, to be indulging in such crass manipulation. Although Curtiz clearly hoped male viewers would leave the theater and go straight to their nearest recruitment center, that is not the film’s emotional impact. When Rick takes Ilsa and her husband to the airport to board their plane out of Morocco, she makes a last-minute bid to stay behind with him. She looks up at Rick from under the broadest and most glamorous fedora brim in screen history. Her eyes fill with doubt and yearning. Then, he gives her a wistful smile followed by the big speech that announces the film’s raison d’être. “Ilsa, I’m no good at being noble, but it doesn’t take much to see that the problems of three little people don’t amount to a hill of beans in this crazy world. Someday you’ll understand that.” She turns, ever so reluctantly, and walks arm-in-arm with her husband toward the fog-shrouded plane. The dialog could not have made matters clearer. The needs of the group far outweigh those of the individual. Sacrifices must be made. (By Hollywood’s lights, what could have been a greater sacrifice than to give up an armful of 27-year-old Ingrid Bergman?) The close-ups overpower the words, however. What we are left with is not a call to action but the unforgettable poignancy of the thwarted lovers parting in the mist, their fedoras and belted trench coats declaring their romantic seriousness. Others may amount to a hill of beans, but not these two. They are stars, and they shine eternally against the collective darkness, just as we hope to in our finest democratic dreams.

After the war, Hollywood’s ethos changed. With the House Un-American Activities Committee sniffing skunks on the set, antifascist films bowed to anticommunist productions with themes that stressed the rights of the individual in an increasingly regimented world. Science-fiction allegories warning of communist takeover were very big, the best being Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956), in which director Don Siegel masterfully created an aura of justifiable paranoia. Using little more than skillful lighting and disturbing camera angles, Siegel translated Jack Finney’s interesting but far less intense novel into a gripping story of coerced conformity in small-town America. In Santa Mira, it pays to stay ever vigilant. Nod off for a few moments, and an alien species replaces you with your placid, soulless vegetable double. The plot sounds passé now, but, at the time, it was, if not wholly new, at least not yet shopworn.

One of the film’s most remarkable scenes is also its quietest, and it depends on a skillfully framed close-up. The protagonists Miles and Becky have taken refuge from the aliens (read: communists) in his medical office, keeping the lights off so as not to be discovered. Siegel places the actors in front of a drawn shade that glows white in the darkness, evidently lit from the outside by a street lamp. As they stand in front of the shade, Becky wonders how people could be succumbing to the aliens so easily. Miles replies that it is not as strange as she may think. In his practice, he has observed his patients losing their humanity by degrees as they age and become more resigned to life’s exigencies. “Only when our humanity is threatened do we recognize how precious it is, as you are to me,” he concludes, kissing her. What does this speech have to do with the film’s plot? In a word, nothing. But it is perfectly in tune with the film’s anticonformity, anticollective theme. This is why Siegel filmed it as he did. By placing his actors against the shade, their heads are sharply etched in profile on its luminous surface. This shot visually emphasizes, as words alone could never do, their irreducible individuality. (Siegel, by the way, always said he was attacking conformists more than communists. Maybe, but since he was married to the communist actress Viveca Lindfors, who had put him through a nasty divorce the year before he made the movie, I’m sticking with the anticommie interpretation.)

Another film of the 50’s, Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront, also deploys the close-up to convey an anticommunist allegory. Working with novelist Budd Schulberg, Kazan set out to tell how Fr. John Corridan, a Jesuit labor organizer, helped honest longshoremen fight union corruption on the Hoboken docks. Kazan and Schulberg also made this film as an apologia for having testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee about their communist past. They saw in their own experience of having been subjected to communist discipline a strong parallel with the dockworkers’ submission to the union code of silence concerning their abused rights.

For its central conceit, the film draws upon the legend of Christ’s mantle, the robe the Roman soldiers shot dice for at the Crucifixion. As the garment was passed on from one man to another, so the legend goes, each found himself compelled to stand up for others. So, too, in the film. When dockworker Joey Doyle is killed for agreeing to testify before the waterfront commission about the union’s practices, he is pushed off his tenement’s roof. After his funeral, his father gives his jacket to Dugan, another longshoreman, who then comes under the influence of Father Barry, the role based on Corridan. Dugan decides he will finish the job Joey had begun, only to be killed in turn. Just before a union goon drops a couple-dozen cases of Irish whiskey on him from a hoist rising out of a ship’s hold, Dugan puts a fifth inside his new garment, quipping that he is enjoying the benefit of being a little man in a big jacket. This is the political and moral message of the film. We are each called upon to become bigger than we are, to face challenges, hardships, and evils that seem beyond our ability to handle. What’s more, we are required to do so alone, for we cannot rely on others to help us carry our crosses. So, after Dugan’s death, the jacket is given to yet another worker, Terry Malloy, who discovers that he, too, must fight the murderous union officials—his former friends, as it happens—on his own. In fact, Father Barry insists he finish the job by himself so he can demonstrate to his fellow workers the power of a single committed man. Malloy redeems his colleagues by standing up to the racketeers. He shows the men that, with courage, they, too, can stand up.

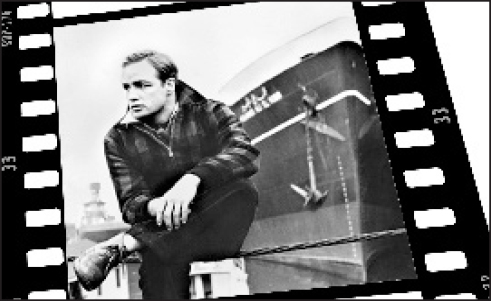

Kazan needed a strong actor to play Malloy, someone who could be believable as a thoughtless thug finally awakened by love and honor to combat injustice. His choice was Marlon Brando, and it is difficult to imagine anyone else in the role, although Frank Sinatra had been considered first. Sinatra, a Hoboken native, may have had the underclass accent and look Kazan required, but he wasn’t a tenth of the actor Brando was, at least not when Mr. Mumbles was fully engaged in a part.

The young Brando’s line readings are as compelling today as when the film was released, especially in his close-up shots. That is where you most notice his habit of looking out past the actor he is talking to as if he were casting in the wind for the words that are always eluding him. Actually, Brando had his lines written on placards and held up by crew members just outside camera range so he could read them while performing. This may seem like self-indulgent laziness; if you watch his performance, however, you will realize it was genius. Rather than making his acting seem awkward as one might suppose, the placarded script makes him seem utterly spontaneous. That is not to say he could not be genuinely spontaneous. Consider that he improvised the better part of a key scene with Eva Marie Saint without knowing in advance he would have to do so. In the park outside Father Barry’s church, he talks to Saint, who play’s Joey Doyle’s sister, Edie. When she drops one of her girlish white knit gloves, an unscripted accident, Saint, as any trained actor would, begins to play through the “mistake,” staying in character. She bends to retrieve the glove, but not quite fast enough. Brando gets to it first. Holding it up, he begins to examine it, and then, to Edie’s—or perhaps, Saint’s—visible annoyance, he pulls it over his own hand. It is an inspired moment—not only because it seems so natural but because it adds such a layer of meaning to the film. This is the moment that Malloy begins to go beyond being physically attracted to Edie. As they talk, he asks her about her attendance at a Catholic college, and she tells him of her aspirations. Having put on her glove, he is entering her world, her vision of what is important, and, above all, her commitment to uncovering the men who took her brother’s life.

Brando could not possibly have foreseen the implications of his split-second reaction to the dropped glove. Indeed, it may never have occurred to him afterward. But he had an uncanny grasp of the theatrical moment. This is the reason he so thoroughly impresses his characters upon us. We cannot turn our eyes from him, because he is at once so instinctive and so controlled, so spontaneous and so deliberate. It is the complexity of Brando’s performance in this scene, shot in both medium and tight close-up, that makes us believe in Malloy as the individual who finally refuses to stay submerged in the gang ethos of his corrupted working-class colleagues, the man who stands up for himself and, thereby, everyone else.

Kazan had a political message to deliver; Brando gave us much more. He gave us its breathing, personal incarnation, the principle of hope in our lives, both alone and together.

We should take solace in the formal conservatism of film. It means we do not have to risk a stroke getting exercised by George Clooney’s next cinematic lecture. What if Clooney’s next film has more to teach us about the rapacity of Americans, the nobility of Middle Eastern sheiks, the decency of communists, the saintliness of Edward R. Murrow? Think of Tyrone Power, and count handsome George’s close-ups. If there are enough, relax. It will be the personal, not the political, that viewers remember.

Leave a Reply