In Ephesians 6, the Apostle Paul writes, “We wrestle not against flesh and blood, but against principalities, against powers, against the rulers of the darkness of this world, against spiritual wickedness in high places” (6:12). Political scientist and lay theologian Jacques Ellul went beyond the usual interpretation of these “spiritual forces” as demons to see in them a kind of aeonic spiritual structure. They are not personal in the sense of evil demons, but they take on a kind of personal power in molding and, in some cases, deconstructing the society around them. There was a demonic spiritual force in Nazism, strongly influenced by a frenzy of antisemitism. It forced the Nazi leadership totally to disregard and reject all of the contributions made by Jews to Germany and European culture. The power of this frenzy over the Germans—and, to some extent, over other Europeans as well—was so great that, in large measure, they tolerated, and often actively supported, Hitler’s morally, theologically, biologically, and strategically insane persecutions of the Jews and other Untermenschen.

It is hard for us today to understand how this happened in a population that was one of the most educated and highly developed groups in the world. It is not enough to blame the Germans as a race or cultural group, as Daniel Goldhagen did in Hitler’s Willing Executioners. The demonic possession of Nazi antisemitism that murdered millions and led Germany into virtual self-annihilation is dead. Isolated incidents of antisemitism still occur, but they are like the shudders of a mortally wounded body; they do not mean that it will rise again to life. The Nazi demon is gone and probably never will return. It is no longer rhetorically effective to attribute its savage effects to “the Germans,” as Germany in her present condition looks like the most successful representative of pan-European multiculturalism. Unfortunately, remembering it and memorializing it, as we are repeatedly asked to do with holocaust museums and courses in schools and colleges, can blind us to the phenomenon that caused it, this “spiritual power of wickedness in high places.”

In the half-century or so since the end of World War II, American society has been suffering decomposition and deconstruction. How can it be that the nation’s body politic has looked on with supine discontent as, by a series of judicial actions, its foundations have been destroyed? Is there a collective blindness? And, if so, where does it come from? Are we, too, under the influence of “spiritual wickedness in high places”? The “power” that infects us does not work as quickly as the demonic force behind Nazism, but it is surely working.

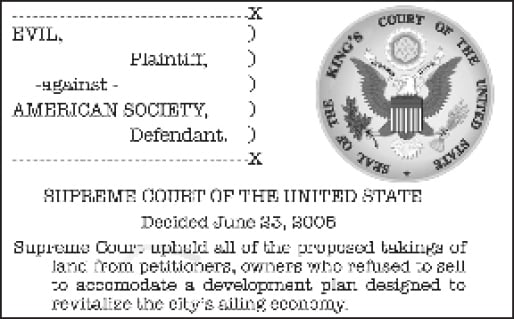

Consider what we have come to in seven decades. The distinctiveness of marriage has been abolished (Baird v. Eisenstadt); prayer and Bible-reading in schools has been stamped out (Abington, Schemp, et al.); the mother’s womb has been made the most dangerous place for a baby (Roe v. Wade, et al.); the rights (but not the duties) of fathers and parents of minor girls have been voided (Planned Parenthood v. Danforth); divorce has become easier than marrying; the Ten Commandments have been banned from public view; and now the natural distinction between male and female is being abolished (Goodridge, Lawrence, etc.) The Pledge of Allegiance is forbidden; the Boy Scouts are under attack; and Christmas carols are banned. Pornography is everywhere.

The structure of American society is being demolished brick by brick. Within a few short years, Americans will have reached the “liberty” desired by Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the abolition of every particular dependency. This is what Hannah Arendt called “the atomistic mass,” a precondition for the establishment of totalitarianism. But the American body politic remains supine, like a fat sow, occasionally twitching or flicking her tail at the pricks of the insects but doing nothing to evade the approach of the butcher.

How can the American people remain ignorant of, or indifferent to, this decomposition? How can we fail to notice that what was once a federal republic, then more or less a mass democracy, has become a critocracy, a land where judges rule? When the judges ruled, there was no king in Israel, and “every man did that which was right in his own eyes” (Judges 21:25). There is no king in the United States; there never has been. But we did not need a king when there were the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God, and when the majority of our people believed that the Creator of Nature has spoken to us in the Bible. There is no longer any God, for judges rule, and we may do only that which is right in their eyes.

The Nazi Party was not a demonor, if so, only in a metaphorical sense. It was the work of human hands. Yet there must have been some kind of a “spiritual force of wickedness” at work, making the Germans blind to what they were doing to others and to themselves. In a way, it might be comforting to think that the Germans are a peculiar people addicted to such behavior, and that we Americans are immune to it. Germans planned and executed the holocaust, but two other nations, the Soviet Union and Communist China, murdered more in absolute numbers. The 60th anniversary of the Allied bombing of Dresden and of the American firebombing of Tokyo has just passed, and that of Hiroshima and Nagasaki is coming. Dresden was not Auschwitz, but the glib self-assurance with which British and American military and political leaders justified the deliberate extermination of civilians rings hollow in the light of Christian just-war doctrine.

In Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Study in the Banality of Evil, Hannah Arendt argues that most of the work of extermination was carried out not by willing executioners, as Daniel Goldhagen would have it, but by unimaginative bureaucrats (of which every modern nation has plenty). Is there not a similar demon, at least a metaphorical one, at work in America, blinding us to what we are doing to others and ourselves? The republic that we thought that we were, the democracy that we thought we had—both are gone, and we have hardly noticed their passing. We once thought of ourselves as a republic—or, rather, as a freely chosen union of sovereign states. The Southern notion that this union could be abandoned by individual, sovereign states—as some in New England had thought during the War of 1812—was crushed by overwhelming military force in the War Between the States. This war is incorrectly called the Civil War, because it was not the goal of the secessionists to control the Union but merely to regain their freedom. The South had no intention of ruling the others. The volonté générale, the general will, became the will of one in the French Revolution. In the United States, the slogan Vox populi, vox Dei (The voice of the people is the voice of God), always troubling, has become irrelevant, for neither the vox populi nor the Word of God counts when our judges speak. When the people have no God, then the voice of those who actually rule becomes the voice of demons, of “spiritual wickedness in high places.”

The people of the United States never chose to be ruled by judges, to replace democracy with critocracy, but that is where we are. For rulers, we have judges. They are no longer chosen, as they once were, by the standard that Moses’ father-in-law Jethro recommended—“able men, who fear god, men of truth, who hate dishonest gain” (Exodus 18:21). “Put not thy trust in princes,” the Psalmist warned (146:3). For our princes, we have taken judges. Many are just, and some fear God. But put a small number of unjust judges in critical places, and critocracy can deconstruct society.

In his Second Inaugural Address and in his campaign, President George W. Bush promised to seek out good judges. It will take more than one or two better judges to rebuild the structures that evil decisions have broken down. This is a reality that challenges our fictional democracy. This evil cannot easily be remedied. Can it be broken? It must be, if we are not to sink languidly into a slough of evil like that into which the Germans plunged in such a frenzy. To break the critocracy, the evil must be recognized. The possibility that it can be recognized is the basis of our hope that America will recover. On the last page of The Crisis of Our Age (1941), Pitirim Sorokin prayed for the grace of understanding, to enable us to make the right decisions to avoid a fiery dies irae. The grace of understanding is one thing that our ruler judges surely do not want, but fortunately, for the nation and for us, the One Who can impart it is not subject to their jurisdiction.

Leave a Reply