Since the time of the Founding Fathers, Protestantism appeared to be the default religion in the United States. At the end of World War II, when the United States began to enjoy superpower status, Mainline Protestantism (comprising the older denominations that sprang from the Reformation) began to drift away from its moorings. Then, in the late 20th century, conservative Protestantism started to follow suit, by watering down its theology, seeking to influence society, culture, and, of course, government.

The older form of Protestant liberalism, and many of its key proponents (including Harry Emerson Fosdick in the United States and the great German historian Adolf Harnack), were heavily influenced by German theologians. Harnack famously limited the scope of the Christian Faith to the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. After World War II, most of the German theologians disdained the “liberal” label—not because they were becoming orthodox or conservative, but because they were inaugurating yet another approach to Christianity. The man most responsible for importing this new approach to the United States was Paul J. Tillich, a German Evangelischer (Lutheran) pastor and professor of theology. He served as a chaplain in the kaiser’s army during World War I, but Tillich’s loyalty did not extend to Germany’s self-appointed messiah, Adolf Hitler. Hitler put him out of his professorship, and he emigrated from Germany to the United States, where he soon enjoyed tremendous celebrity. Those of us who sat under him at Harvard Divinity School were awed by his apparently universal brilliance, but some also came to doubt his authenticity. Tillich and other mid-century theologians disdained the liberal moniker; they insisted (correctly) that they had gone beyond liberalism. Precisely where they were headed was not obvious, at least at first—so much so that one of my conservative Protestant friends suggested to me that, having extended a call to Tillich, the generally Unitarian Harvard was becoming conservative.

While enrolled at Harvard Divinity School, I served as an advisor to freshmen at the college. A benevolent dean of freshmen occasionally assigned priests’ and pastors’ sons to me as advisees—probably hoping that I might cushion the shock they would feel at the increasingly pagan Athens of America. One lad, the son of a Bulgarian Orthodox priest, was in spiritual turmoil and told me that he intended to go hear Tillich preach. I encouraged him to go elsewhere, but, like most late adolescents, he disregarded advice and went to hear the famed theologian (now a visiting professor). When I saw my advisee again, I asked him what Tillich had preached about. “Decision,” he replied, which was not surprising, since that was an important concept for Tillich.

“How did you like it?” I asked.

“I felt like standing up and shouting, Then decide, you bastard!”

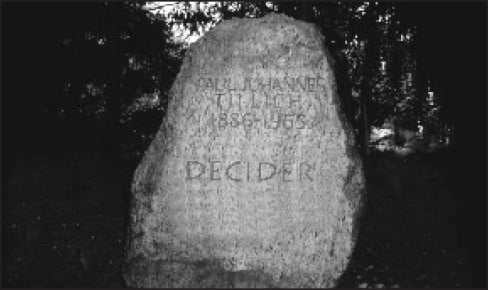

Many of us listened longer before coming to that conclusion. It took me quite a while to decide whether the master’s wisdom was elusive or illusory. Even in English, the fact that his oratorical skill was so great and proffered with such commitment led some of us to conclude that Tillich’s goal was to display eloquent brilliance, not to convey truth. Whether his faith in the Ground of Being—or, more precisely, in the Meaning Ground of All Being (der Sinngrund allen Seins)—carried the day for him when he met his Maker is not for us to know. He was born in 1886, the same year as Karl Barth and Rudolf Bultmann, and suffered a fatal heart attack in 1962, after listening to a lecture by one of his former students, Thomas T.J. Altizer, on the death of God.

Tillich overwhelmed most of his auditors with his brilliance. Not many reacted as my Bulgarian Orthodox advisee did, but that, it seems to me, was an appropriate reaction. After listening to Tillich talk about the authenticity of religious symbols, a fellow student, Vincent Brummer, who later became a professor of philosophy in the Netherlands, asked, “Do you mean that all religious symbols are valid because they are authentic expressions of man’s quest for the divine, but the Cross is supremely valid as the symbol of God’s quest for man?” That’s it, I said to myself, sitting next to Vincent.

“Oh, no,” Tillich replied, “you totally misunderstand.”

When Tillich lectured on Mondays and Wednesdays at Harvard, practical theology (preaching) was on Tuesdays and Thursdays. Thus, many student sermons often included a watered-down imitation of the previous day’s call to “decide,” without clarifying what that decision should be. His emphasis was not on Who Jesus is and what He has done for us, but on the existential impact that His message has on the hearer. “What does the New Testament want?” was one way to express it. For the Bible is not there to teach historical facts but to change our lives. Tillich once said in a lecture that even if all of the police records of first-century Roman Palestine were assembled and no trace of Jesus and His crucifixion were to be found therein, it would not trouble him, for he had already experienced the New Being through the Gospel.

Tillich has been gone for four decades, but his works are still read, and, wittingly or not, his approach has become typical of many of the Protestant churches in America. In many ways, Tillich’s thought resembles that of Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768-1834), who sought to save Christianity from its critics by emphasizing its effect on the soul, “a feeling and taste for the infinite.” Schleiermacher was called by some the founder of liberal theology, for which feeling became more important than fact. From its beginnings, Protestant teaching had emphasized the internal transformation that the Gospel brings about in the believer’s heart. Formerly, most Protestants believed that such a transformation is grounded in the fact that the Gospel story is objectively true, not in the observation that it is existentially moving.

Tillich’s call for decision and authenticity was not tied specifically to any creed or confession for which to decide. He saw modern man caught in a dilemma between his desire for autonomy (to be a law unto himself) and the threat of heteronomy (rule by heteros, the other), which was embodied in Hitler. The solution that Tillich proposed is very good advice, as were many things that he said, if one is careful to place them in the proper context: theonomy, law from God.

In principle, every Christian should be a theonomist, bowing before God and obeying His laws. Unfortunately, the term theonomy, like so many simpler words—obedience, honor, virtue, purity, and many others—has lost its clear meaning and has even become odious. When people hear that word today, they think less about a Christian’s obedience to God and more about his duty to establish a government based on a strict interpretation of Old Testament law. Thus, former Republican strategist Kevin Phillips has written American Theonomy, in which he claims that anything and everything that conservative Protestantism has had to say about politics in recent years has been nothing short of an attempt to establish church rule in the United States.

The late Rousas John Rushdoony (1916-2001) taught a different kind of theonomy. Rushdoony believed that, if a Christian recognizes God as sovereign, obedience to His commandments logically follows. He wanted to make all biblical law—not just the clear moral teaching of Scripture—mandatory for the whole of American society and, ultimately, the world. If his ideas were adopted, society would certainly be transformed, but not without breaking many eggs—and heads. After all, in his schema, sexual transgressions such as adultery and sodomy would be capital crimes.

Today, a small but vigorous fellowship of Christian Reconstructionists, who revere the teachings of Rushdoony, seeks the reordering of society according to a strict reading of Old Testament law. They certainly make up too small a group to merit Kevin Phillips’ grave apprehension. Although there is hardly any chance that this kind of theonomy will one day govern America, the mere preaching of it has had an unintended effect: It has fueled a tendency in legislatures, in the courts, and especially in the media to repress any Christian moral criticism of sexual conduct.

In the early decades of the 20th century, when the intellectual centers of American Protestantism were coming under the influence of German liberalism, those institutions began questioning the authority of the Bible, in general, and the authenticity of its books, in particular, all the while holding on to what had generally been the accepted Christian morality—only now, without justification. This ungrounded morality took shape in the Social Gospel, which emphasized practical Christianity, good works for the multitude, and ministry to the poor and disadvantaged: “Doctrine divides, service unites.”

To conservative Christians, these developments meant the substitution of morals for faith, which amounts to a denial of salvation by grace through faith. Because there was no established Protestant church in the United States, the reaction arose spontaneously in various quarters and with different emphases—some, politely academic; others, vehement and denunciatory. All fought for the preservation of biblical authority and “fundamental” Christian doctrines: the Trinity, the deity of Christ, His Virgin Birth, the bodily Resurrection, and salvation through Christ alone. There were outstanding scholars among them, including J. Gresham Machen, the great Princeton theologian and founder of Westminster Theological Seminary, and Carl F.H. Henry, the founding editor of Christianity Today; and there were those who were more rigid and whose chief focus was on maintaining a public and distinct separation from liberals and their own wavering brethren, who proudly claimed the name fundamentalist. The more biblical name evangelical was preferred by Henry and came to reflect those who were willing to compromise on nonessential issues.

As David O. Moberg wrote in The Great Reversal: Evangelism Versus Social Concern (1972), this concentration on embattled doctrines over a period of several decades made social issues secondary among conservative American Protestants. Many evangelicals who upheld the fundamental Christian doctrines began to sense that their lack of attention to social issues was a failure. They began to break into public prominence with the appearance of Billy Graham, a young evangelist from North Carolina, whose “crusades” began in 1948. Graham was the greatest of mass evangelists but not a social activist. He helped to found Christianity Today, which tended to idealize him and his work of mass evangelism but also began to express social concern. By establishing the magazine’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., Carl Henry and many of its board members hoped to replace the liberal Protestant Christian Century as the leading Christian voice to the nation’s leaders in government.

Under Henry and, to a lesser degree, his successor, Harold Lindsell, Christianity Today attained a high level of academic respectability but received little attention from the government offices that surrounded it, as its focus was too theological for their tastes. A substantial grant from wealthy evangelicals allowed the magazine to offer free subscriptions to all of the students in America’s Protestant seminaries, where its ongoing intellectually sound defense of scriptural and theological authority provided a valuable counterweight to the prevailing liberal spirit. After undergoing a financial crisis in 1973, the magazine moved to Carol Stream, Illinois, near Wheaton College.

That same year saw the handing down of the watershed Supreme Court decision Roe v. Wade, which voided the abortion laws of every state and the District of Columbia and made abortion-on-demand available throughout the nine months of pregnancy. Immediately, Harold Lindsell grasped the enormity of Roe and appointed me (then an associate editor of Christianity Today) to write the lead editorial. Naively, we thought that the decision was so atrocious that vast numbers of evangelicals would rise up and lock arms with Roman Catholics to demand its reversal.

Instead, tranquility prevailed. Some Protestants acted as though opposing Roman Catholics was their first and greatest commandment. The Christian Action Council (now Care Net) was founded in 1975 when the ongoing slumber of evangelical Protestants became undeniable. It took the work of an American theologian who had emigrated to Canton Vaud, Switzerland, Francis A. Schaeffer, to disturb it. Together with his gifted son Franky (now an Eastern Orthodox Christian) and noted pediatric surgeon C. Everett Koop (who would later serve as U.S. surgeon general in the Reagan administration), Schaeffer produced a series of short films entitled Whatever Happened to the Human Race? Shown in churches, schools, and homes around the country, it so thoroughly aroused viewers that the term evangelical has come to be synonymous with anti-abortion.

From Tillich’s call to decision to Schaeffer’s guidance on what to decide, conservative Protestants have come a long way. Schaeffer, unlike his fellow evangelical Billy Graham, taught that Christians have a duty to go into secular society and influence it for the good, which is similar to Rushdoony’s vision. Their goal, however, is not to compel obedience to God’s law but to persuade their neighbors to follow it. Unfortunately, far too many Christians today seem to be following in the footsteps of the Mainline liberals, trading social concern grounded in theological conviction for mere social concern. And it is their lack of theological conviction that makes them easy prey for the politicians who pay lip service to their social concerns. For those who dangle the carrot of incremental theonomy before genuinely concerned Christian voters, the hour of decision has little to do with the Gospel and everything to do with the polls.

Leave a Reply