I do not live in a painting by Magritte or by De Chirico or even by Carmen Cicero—no, really, I don’t, honest, scout’s honor, no kidding—but sometimes I get the creepy sensation that I do. That sinking feeling is an identifiable vertigo not caused by imposing stimuli, such as intimidating heights, but by lesser, humdrum disconnects, such as standing by a door or in a parking lot or walking on the sidewalk and hearing a conversational tone from a stranger addressing the void with a Nokia cellphone in his hand. It is the tone of voice, private in public, that seems surreal, I suppose. But then, there is the compensatory emergence from dissociation as cognition gathers through the recognition of the banalities that are uttered: “Yeah? . . . I dunno . . . Me neither . . . What you wanna do? I dunno. Whatever.” There somehow seems a discrepancy between the inanities transmitted and the pretentious medium of transmission, the vehicle of which is, unlike much else except vodka, imported from Finland. The big deal is to some degree lessened through its ubiquity, but, make no mistake, in its unmistakable vacuity, the phenomenon is a big deal. The appurtenances of contemporary existence don’t offer much in the way of excitement or in the regeneration or life department, but the hype is relentless.

The gap between the promise and the humdrum reality has been a feature of modern life a lot longer than cell phones have been. Modern politics was supposed to deliver us from all the oppression of the past—that’s a good one! Modern society was supposed to liberate us from constraints and illusions. And modern technology was going to be the vehicle to create a new world with a new consciousness. What a bummer that the new consciousness too often means being a dope.

The melancholy long withdrawing roar caused by the empty promises of modern society has been felt for a long time, but it has not often been understood. Though romanticism was one form of that melancholy, that mode has been politically misconstrued and manipulated ever since. Even so, one neopagan romantic managed, in the style of Diogenes, prophetically to attack the blather of technological innovation a century and a half ago in a manner Thoreauly attuned to our moment:

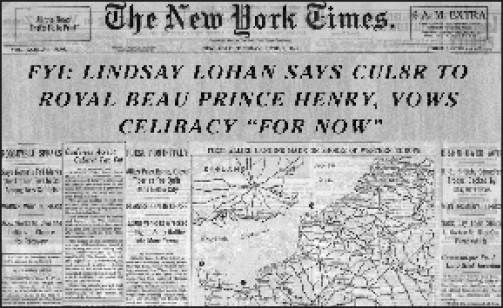

We are in great haste to construct a magnetic telegraph from Maine to Texas; but Maine and Texas, it may be, have nothing important to communicate. . . . We are eager to tunnel under the Atlantic and bring the Old World some weeks nearer to the New; but perchance the first news that will leak through into the broad, flapping American ear will be that Princess Adelaide has the whooping cough.

Well, it is not far from the princess’s whooping cough to the hanky-panky of Paris Hilton, so here we are—or, rather, there it is. The mountain labors and produces a mouse. But we can linger in the precincts of the old technology before we get down with all the new hot stuff.

Thoreau did not have much use for newspapers and was even hostile to libraries, and perhaps we can understand his disposition, as time has revealed even more problems than he knew. Of course, newspapers have long since “gone online,” but they still appear in their pulp analogue format, and they still have their readers, of whom I am not proud to be one. My own attention to newspapers might be called an addiction or, more accurately, a bad habit (or even a superstition, because attention averts worse news). Fifty years of morbid fascination tells me that newspapers have actually declined in quality since I started reading them. Take the New York Times—please. When I started reading the “Gray Lady,” I was impressed by its air of objectivity, its international coverage, and its sober attention to the arts. Well, I was young and had not then heard about the Stalin embarrassments, but I was around for the Castro puffery. The Times still maintains an air of objectivity, though, today, that air is but an affected poof. The coverage of the arts has long since been a complete sellout to the fraud of contemporary incompetence, though here we must realize that the Times cravenly followed and did not lead the trends. But the international coverage—whoa! I particularly relished the issue of March 20, 2006, which featured a bonus section, a “special advertising supplement” of eight pages, sponsored by the “government” of Sudan. The cognitive dissonance became overwhelming as I remembered all the editorials about the genocide in Darfur and the op-ed pieces about the genocide in Darfur and the news stories about the genocide in Darfur and the calls for intervention in Darfur and even for bombing in Darfur. They somehow did not square with all the pages of drooling and slobbering about oil in Sudan and minerals in Sudan and banking in air-conditioned splendor in Khartoum and the two banking systems (one based on sharia) and all the other opportunities for international financiers like me. The money would explain a sentence such as “Ministers are frustrated that coverage of Sudan in the international media has focused almost exclusively on the fighting between rebels and Arab militias in the western province of Darfur.” Mutilation, rape, and slaughter is something more or less than fighting, but we do make exceptions if the victims are Christians, as the Times has done before.

But enough of the “Gray Lady,” or, as she has come to be known more appropriately, the “Old Slut.” Let us relate instead to something more contemporary, more now, more connected to what’s going on. And yes, I am thinking about the blessings we find on cable and satellite television, and all of the bills that we receive as the rates are approved by the government to support our need for so many exciting channels! And it is hard for me to distinguish between my excitement at the number of channels and my glee at what is on those channels and my political joy at the segmentation of the channels, which, by uncanny coincidence, is framed around the ethnicity, race, religion, sex, orientation, and age of putative viewers, so that the service providers are better equipped to provide service to the diverse needs of the community and its diverse community needs.

Of course, I have access to only a limited number of channels myself, but I do not feel too constrained about that, especially not after a friend explained to me that he recently acquired 500 channels and flipped through all of them only to conclude that there was nothing on TV. Somehow, I was not surprised. But there can be difficulties, even with 500 channels. For example, I am aware of at least five pornography channels, and these could present a difficulty if you are married (as I have heard professors seriously discuss), or even if you are not—for how could you distinguish between the Hot Network, the Hot Zone, Playboy TV, Spice Platinum, and A Taste of Spice, except by assiduous study? Furthermore, there is a new problem, because, with at least two new “gay” channels, we now have to wonder how the service providers can provide service to such a diverse community (gay, lesbian, transgender, bisexual) in order to serve equitably all the equal needs of that adult-subscriber market segment as determined by focus group.

Leaving the agonies of that problem aside, there are some other issues with the media in all their fulsome development. One of them is simply how to find out what the news is, especially if you are tired of the Old Slut and of the tabloids with all their pictures of such ladies as Madonna and Mariah Carey and Lindsay Lohan and all the rest of them. But strangely enough, even with all the channels, the news is more remote than ever before. I mean, what is the news anyway, after all? A phenomenological response would be something like this: Though, decades ago, the news looked like Walter Cronkite and seemed sometimes at least to be a chronicle of events, now the image of the news is a lot more like Lindsay Lohan, but dressed, preferably in a jacket without a blouse, so that her nude chest is only one button away. So you can catch the news and hear about the price of oil while thinking subliminally about something else, which makes the news rather spicier, n’est-ce pas? And, in case yours is a different orientation, the news might also be the image of a girly-boy looking quite suave and mellow with a really together hair treatment and ensemble, and, if so, laissez les bons temps rouler. But even then, after such a roll in the hay, you still do not know what the news is, because somebody does not want you to.

Without basic information or coherent accounts of salient issues, however, there are a lot of channels and a lot of time to fill. This is where Scott Peterson comes in, and all the other murder stories and dog-bites-man stories, not to mention all the rock videos, the police videos, the amateur videos, the professional steroid sports, the pre-formulated discussions, the white-trash exhibitionism, Oprah, Dr. Phil, Regis Philbin, and calls for bombing (but not in Darfur) from detached and thoughtful observers such as William Kristol.

And we have to admit that the news is not the only thing you cannot find out about on television; history is a problem, as well. That is why my favorite channel is the History Channel, because, like Agent Mulder and even Agent Scully, I am really interested in UFOs and the government cover-ups and the abductions and the conspiracies and the Bermuda Triangle, the Loch Ness Monster, Big Foot, and the conspiracy to cover up the children Jesus had with Mary Magdalene (those little trolls!), which, I thought, was treated with historical nuance and with all the concern for Christian sensitivities that we have come to expect.

I have wondered, however, about what is now the Military Channel, which was consolidated from others, including the old Wings Channel, because, after all, there is only so much footage that was shot in the last few wars. A great deal of that footage is about bombing—carpet-bombing, dive-bombing, precision bombing, torpedo bombing, para-fragging, strafing, and, more recently, cruise missiles and smart bombing, played over and over again—they have more surprises on the adult programming, though how would I know that if I do not watch it? But why so much bombing? I just have no clue—what interest could that possibly serve? Then there were the color films of GIs summarily executing wounded Japanese soldiers in the Pacific campaign—that was something remarkable about the Greatest Generation. But when all the bombing was exhausted, they just went back to lots of Adolf Hitler recycled endlessly, seeming to share at least some footage with the History Channel. Again, I was at a loss to explain the Hitler stuff, but I figured everything was OK because somebody higher up was making all the decisions and it was for my benefit. I learned that Hitler spoke German in a harsh manner before big formations of soldiers, had bad teeth, and has been dead for six decades. Then I learned it again. Why was I supposed to remember Hitler when juvenile delinquents and skinheads are supposed to forget him? I realized that meant that I was not juvenile or at least not delinquent (though I seem to be becoming a skinhead through attrition) and felt much better about the whole thing when I saw that the best thing on satellite TV is anything with Roger D. McGrath.

McGrath, however, is a notable exception. By and large, the “vast wasteland” that was identified more than four decades ago has become even more vast than the half-vast wasteland we knew in the old days of broadcast channels. In the meanwhile, there have developed other modes of communication that present challenges and opportunities of their own. The internet is one such. Not invented by Al Gore, Al Gore to the contrary notwithstanding, the internet was developed from military sources, so that the internet is, among other things, a system of surveillance. Watch yourself. Internet activity has already been introduced in trials, so that visiting the wrong website can actually be a criminal matter. We must add that various sites and blogs can be misleading, wrong, dangerous, and even prurient. The web of connections can move quickly from legitimate historical information to gross terrorist solicitations, as I have myself experienced. At the same time, of course, the internet can be a marvelous instrument for research, but only to the experienced hand. Turning young people loose on the internet is a dubious proposition at best, and everyone should understand that e-mails are permanently recorded. These are some of the blessings of the millennial wonders brought to us by contemporary technology—but only some.

We return to the cell phone, that destroyer of distinctions and propriety, and its developing capacities, ones that are hard to keep up with. Cell phones today can stream video clips, store oldies but goodies like an iPod, take digital photos, and even transmit those photos internationally in only a few seconds. Soon, cell phones will be doing even more. But now is the time to reflect on the charming institution of “text messaging” or Short Message Services, a.k.a SMS. In the world of SMS, “communication” has been reduced to the hip gibberish so dear to the unenlightened. “Studying” SMS can boost your creativity, so that you, too, can participate in the creation of a moronic subcult. SMS has many benefits. Suppose that the word great is too hard to spell out—we substitute GR8! ASAP was stolen from the old writing culture, once quaintly called an acronym. So is SWAK; so is FYI. But how about CUL8R? Or Ht4U? Or RUOK? Well, those are pretty easy, but AWHFY? signifies “Are we having fun yet?” Is this cool or what?

But wait, it gets even cooler. The gibberish known as “leet” (or “l33t”) has reached a new low in pointlessness but is nevertheless extremely irritating, and so are “emoticons.”

The big business propagated by contemporary technology leaves us far from heaven, but not far from monomaniacal bloggers and paranoid fantasies. Some of the bloggers are good guys, and some of the paranoia is justified. On the whole, however, the possibilities of noble aspiration and of cultural elevation have been scanted. Television might be a vehicle for enlightenment and education and aesthetic refinement, but that is rarely the case. Television seems to be an instrument of political obfuscation, a babysitting pacifier of stay-at-homes, and yet another venue for rock music. Not many people load their iPods with worthy music—they want, instead, chewing gum for the mind, and they get it in every venue. That suits the powers that be and is very profitable as well.

With the news hard to find, and its meaning obscured by many noises and much confusion, those doubtful of instant bliss and heaven on earth will have to find ways to use the emerging technology to their advantage rather than for their own oppression. The internet can be used for all sorts of benefits, such as shopping nationally for exotic used cars, for obtaining boutique foods, and for all kinds of information; and millions of people take advantage of it every day. On the other hand, computer skills are no longer required for setting up a website—almost anyone can do it quickly, and does. Ditto for podcasts. The technological obscurities and convergences seem both to have opened the gates for independent voices and to have raised the level of confusion. The discrediting of the old broadcast channels of the mainstream has also cast doubt on the fringes, as proliferation has flattened the horizon and maximized doubt.

So, just as examples of the old culture, such as books, have to be approached with perspective and discrimination, the opportunities and traps of the new culture have to be examined with a skeptical eye. There is hardly any aspect of the contemporary media that is not a betrayal of a possibility, but those problems will have to be sorted out individually. There are, in the meantime, some possibilities to enjoy or to experience. David Cronenberg’s 1983 thriller Videodrome, recently released as a DVD by the remarkable Criterion Collection, is a striking vision of the older technology—James Woods has a VHS slot in his stomach—and perhaps an intimidating fantasy as well. This treatment of the perversions of technology may be called a pessimistic reification of the ideas of Marshall McLuhan and a salutary nightmare into the bargain. In Cronenberg’s film, technology is used to critique technology.

And that was, mind you, 23 years ago. How would we attack the problem of the media in all their proliferation today? My answer is, turn the technology against itself. Put Mozart on your iPod. Use compact discs to play old recordings—78’s live again! And best of all, forget about watching all the channels, for—let’s face it—the art of film is pretty much dead. All that is needed is a private library of DVDs and a powerful digital projector in a darkened room. Those pixels really light up when you ignite them with enough lumens. Those old flicks have a renewed glamour in such conditions—actually better than in the original experience. Norma Desmond can still fiercely intone that she is still big—it is the pictures that got small—and mean it, and be believed, as never before. In such a moment of rapture, the film addict is fixed in an ecstasy that justifies the technological means. Better the insanity of the fictional Norma Desmond than the perky “sanity” of the all-too-real Katie Couric.

Leave a Reply