Texas attorney general and gubernatorial candidate Greg Abbot committed what is commonly called a political gaffe earlier this year when he said what every thinking person this side of the Rio Grande already knew: Mass immigration from Mexico means the importation of Mexican corruption and the steady erosion of law and social trust that too many Americans take for granted. The attorney general spoke of “creeping corruption” and “Third World country practices” that “erode the social fabric of our communities,” a process that is quite advanced in South Texas, which is already well on its way to “assimilation” of a kind no sensible Texan can abide: They are not becoming us; we are becoming them. Abbot’s “insensitive” remarks were all the more surprising coming from a mainstream Republican politician and may have been an early sign of what Texas patriots had long hoped for: a sea change in attitudes about the state’s steady merger with the narco culture to our south.

Abbot did not elaborate, but those of us with eyes to see and defective thoughtcrime mechanisms knew what he meant: South Texas sheriffs and their deputies working for drug cartels or robbing drug runners to sell the goods themselves; Border Patrol officers taking bribes to turn a blind eye to drug shipments and “human trafficking”; and judges selling their rulings. The corruption market has a way of expanding along with the masses of “migrants” from south of the border, as the reverse-assimilation process is driven by racial replacement. In one South Texas town, the mayor and his brother, who was serving as school-board president, took payoffs from enterprising souls hoping to do business with the school district. In practically every case (at least every case with any names given), the accused are Hispanic.

With “Anglos” already a minority in the Lone Star State, the siren call of racial solidarity grows harder to resist among Mexican-Americans born and raised this side of the border, many of whom have close relatives in what Texans used to call “old Mexico.” Add to the steady drumbeat of media, academic, and politically driven anti-white, anti-American propaganda a chorus of Hispanic triumphalism, the practical disappearance of celebrations of Texas Independence Day and San Jacinto Day (marking the victory of Sam Houston’s Texan forces over Santa Anna’s army), along with the corporate promotion of Cinco de Mayo as their replacement, and it’s not so hard to see why a “flight from white,” a rejection of all things connected to Texan, Anglo-American identity and cultural norms, is growing among Hispanics. Sheer numbers matter. Cultural cues matter.

The territorial bounds of reverse assimilation will not—and have not—remained steady: The reach of Mexican-style problem-solving is steadily encroaching on North Texas. In May of last year, for instance, Mexican attorney Juan Jesus Guerrero Chapa, later identified as a narcoabogado (a lawyer for drug dealers), was assassinated in broad daylight at a shopping center in affluent Southlake, a Dallas-Fort Worth suburb that had not recorded a homicide since 1999. Guerrero, who some media sources later reported was cooperating with U.S. authorities, had defended a number of members of the notorious Gulf Cartel. Like many other wealthy Mexicans, Guerrero and his family had taken up residence in Texas, seeking safety in what media reports described as a “highly secure gated community” in Southlake.

In the period after the “execution” of Guerrero, reporting on the murder made it clear to anyone who was paying attention that this story was only the tip of a very large iceberg, shattering the perception that Mexican criminal organizations do not operate in the open on American soil. Texas Department of Public Safety Director Steven McCraw told Fort Worth’s Star Telegram that Mexican drug cartels were the greatest organized-crime threat to the state, and one DEA official called Dallas-Fort Worth a major “command and control” center for the operations of six major drug cartels using the North Texas transportation hub as the link in a supply chain that was spreading across the United States, even as Mexican gangsters north of the border branched out from drug and human trafficking to extortion, contract murder, kidnapping (practically an industry in Mexico), oil theft, money laundering, and auto theft, with telltale corruption following.

The U.S. military, penetrated by street-gang activity in the ranks, is reportedly becoming a recruiting ground for cartel hitmen. In 2009, for instance, a Fort Bliss, Texas, soldier, Michael Apodaca, was recruited by cartel operatives in Juárez to carry out a contract murder in El Paso, long a safe haven from the bloody world of “murder city” across the border. U.S. officials believe that Mexican cartels are actually instructing gang members to join the U.S. military for training and access to more potential recruits. Some law-enforcement officials think that the precision of the Guerrero murder in Southlake points to it being carried out by current or former military personnel.

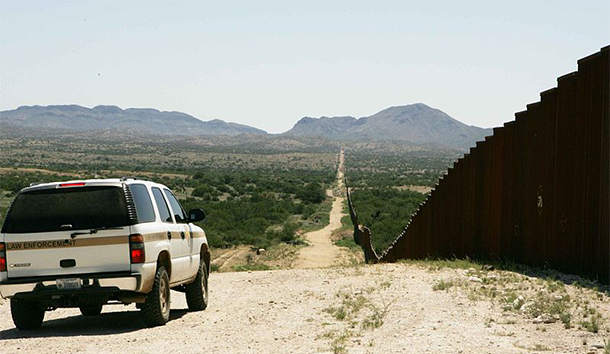

More recently, political signals from the White House, as well as from members of Congress from both parties, that a mass amnesty for illegal aliens living in the United States was in the works have set off another wave of illegal “migration,” and the Obama administration has practically stopped deporting illegals held in detention. With Texas detention facilities overwhelmed, federal authorities began shipping detained illegals to Arizona (prompting Arizona Gov. Jan Brewer to complain of the feds “dumping” them in her state), while mass media have played up the stories of large numbers of unaccompanied children being detained near the U.S. border as part of an “humanitarian” justification for an amnesty. At the same time, according to a report issued in May by the Center for Immigration Studies, the Obama administration has released 36,000 criminal aliens convicted of crimes ranging from murder and kidnapping to drunk driving. The powers that be, dead set on “electing a new people,” are doing everything possible to flood the country with aliens, creating an “humanitarian crisis” that will lead to inevitable calls for “immigration reform” and the de facto erasure of America’s already porous and unstable southern border.

Texas Sen. Ted Cruz pointed out that the artificial crisis was a “direct consequence” of the administration’s actions and rhetoric regarding illegal immigration. “We need a president who is willing to uphold the law,” said Cruz, who added that the White House had “handcuffed” the Border Patrol.

Maybe this time, enough really is enough. The Texas Republican Party, which was notoriously silent on George W. Bush’s own lawlessness, just may be changing course, however belatedly. At the GOP state convention in June, the party platform’s “Texas solution,” a guest-worker-style veiled amnesty, was replaced with a plank that rejected amnesty and also rejected plans to increase legal immigration, given current unemployment levels. (A common political ploy of GOP politicians has been loudly to denounce illegal immigration, while quietly supporting increasing legal immigration, even during a recession.) It’s not an immigration moratorium, but it could be a significant step toward sanity in immigration policy. Senator Cruz (of Cuban extraction) gave a strong anti-amnesty speech at the convention and was the overwhelming winner in a presidential straw poll. The victory of an outspoken critic of open borders, Dan Patrick, in the Republican primary for the lieutenant governor’s spot (a very powerful position in Texas), may also be a sign that Texas Republican voters are reacting to the existential crisis that mass immigration represents.

We can only hope so.

In Mexico, drug-cartel operatives offer police, judges, journalists, and state officials a very simple choice: plata o plomo (silver or lead). They can take the cartel’s money and cooperate, or die, quite possibly taking their families along with them. Imagine, if you can, the everyday life of people in countries all over the world where contact with officialdom often means paying a bribe; where any routine police stop can mean extortion, if not worse; where paying off a judge is the best, and perhaps the only, way to obtain a fair hearing; where the army is but another criminal cartel; where everything from politics to small business is corrupted by extortion and payoffs; where the state and the criminal world overlap or are fused; where to own property means constantly being on guard, and obtaining property means having the right connections; where the law is an empty formality; and where trust is a rare thing in one’s life outside a narrow private sphere. Plata o plomo. If present open-borders trends continue—they are not indicative of some irresistible force of nature, but of conscious policy choices by our globalized elite—then our posterity will likely be living in a country very much like that.

Leave a Reply