“Woe to the Assyrian, he is the rod and the staff of my anger,

and my indignation is in their hands. I will send him to a deceitful nation . . . ”

—Isaiah 10:5-6, Douay-Rheims

Confronted by the rise of insurgent Islam and the political reality of jihad, many Christians, eager to formulate a response, have turned to the Crusades. Can the rationale for the Crusades be transferred to, or imposed on, the “War on Terror”?

In order to understand the theological case for the Crusades, we must carefully attend to the notion of theological argumentation that obtained in the Middle Ages, setting aside current styles. The perspective of the historian is necessarily ruled out, even if he may discover or collate or provide the texts from which the theological rationes are to be culled by the theologian. An approach that makes use of a posteriori evidence of what is often abusively called “popular piety” or “ideology” or “propaganda”—or, if we are of a more traditional bent, of a certain positivistic romanticism about Europe and the Christian Faith—will not yield an understanding of what for its preachers was an enterprise logically deducible from the scientia Dei et beatorum, “the knowledge of God and the blessed,” the authentic expression of which is to be found on the sacred page of Holy Writ.

Theology is both a speculative and a practical science. It is predominantly speculative, since it regards truths that are immutable, metaphysical, and supernatural, but it is also practical, since theology treats as well the means of arriving at the permanent possession of the immutable things contemplated. In his lessons on the First Book of Peter Lombard’s Sentences, St. Thomas Aquinas tells us that if theology were merely speculative it would concern only the present, but since it also considers the practical way to attain happiness, it concerns the future as well—the resolutions to be made and the actions to be undertaken in order for wayfarers to become possessors of everlasting bliss.

A certain kind of contemporary “theology” now in decline has, under the aegis of Heidegger, seen theology as a work of historical interpretation, set on God as the “ultimate future” of man. There is no place for the sort of initiative that seeks to place human society under the sway of an objective revelation, which is always present and immutable, atemporal and transcendent. Instead, it speaks only to the men of this time of the things of this time. It has no place for crusades, but it also has no place for universal creeds or catechisms, as Karl Rahner makes clear in his vesperal résumé of his own thought, Foundations of Christian Faith.

The “ultimate future” of medieval theology, on the other hand, is always an absolute and realized present; it is the historical future that is concretely relative, determined simply by whether or not men take up the means given them by God to arrive at the perfection and bliss of the heavenly society already established with the creation of the angels.

How do men determine what these means are? By examining the authoritative text of the Bible. We who are heirs of the Reformation or the Counter-Reformation can scarcely appreciate, albeit perhaps for different reasons depending on our allegiance to the one or the other, the serene conviction of the medieval Catholic theologian, and in the first place of Saint Thomas, that all theological reasoning, to the extent that its conclusions are certain and undoubted, must be resolved to the first principles of this queen of the sciences—namely, to the words of Sacred Scripture. In the same lectura romana on the Sentences cited above, Saint Thomas answers the question whether the writings of the saints (of the Fathers most especially) may be used in theological reasoning. His answer is a very qualified sic, “yes,” coming close to a formal non, “no”:

In the case of theology, in the place of the principles which are self-evident there are the rules and articles of faith which are handed down (traduntur) in the canonical scriptures, and therefore the arguments which proceed from them take the place of demonstration. The arguments of the saints on the other hand are like probable reasonings, whence it is permitted to use them, not as establishing a necessary argument, but as providing a certain probability. Only those things which pertain to the rule of faith handed down in the canonical scripture impose the necessity in matters of faith.

We may know of the example of the saints, we may know the historical progress of the Crusades, but do we know the reasons whereby those who undertook the Crusades were persuaded beyond a doubt that they were justified and, indeed, obligatory? For them, the Crusades were not a matter of historical interpretation, a culturally self-conscious analysis, but a serene and immediate practical resolution to be undertaken because the Word of God demands it.

“And he changeth times and ages: taketh away kingdoms and establisheth them.” In his July 1091 crusade bull for the reconquest of Tarragona in Spain and in an October 1098 letter to Bishop Gerland of Agrigento, Pope Urban II makes use of this passage from the Vulgate version of Daniel to explain the success of the Christian reconquest of Sicily by the Normans. In the latter letter he links the passage from Daniel to the first chapter of Ephesians, which tells of the marvelous summing up of all things in Christ “according to the purpose of his will.”

A medieval pope would not have consulted a concordance for a proof text but would have known the whole context of a citation and its implications. The reference to Daniel is from the time of the pagan conquest of Jerusalem and the captivity of the chosen people in a context containing a prophecy of Christ the Virgin-born who would establish an everlasting kingdom. And this is linked to a New Testament parallel found in Saint Paul’s praise of the divine plan in Ephesians 1, in which “God’s will and purpose” is precisely “in the dispensation of the fullness of times to reestablish all things in Christ, that are in heaven and in earth in him.”

With this scriptural reasoning, Urban offers the most theologically lofty rationale for a crusade—the divine plan of bringing everything into subjection to Christ, which is the dogmatic key for understanding human history—a rationale that includes even the evil which the Crusades had been undertaken to confront. This is an eschatological perspective, but it is one that governs the whole arc of human history viewed in the light of the Incarnation of the Word. It is not only something to be realized at the end of time but a principle of understanding and Christian initiative at every time.

This same Urban II’s famous and variously reported sermon at Clermont (1095) is nothing but a conscious application of the words of Scripture—about Jerusalem and the course of history until the coming of the Antichrist—to the Pope’s proposal of what became the First Crusade. From Urban’s chain of arguments taken from the Gospels, the epistles, from the prophets, psalms, and historical books, the Christian can only conclude that the Holy City must be defended and restored.

Long before Clermont, Hildebrand (Pope Gregory VII) had offered cogent Johannine reasoning for undertaking the crusade to the East: Because Christ laid down His life for us, we ought to lay down our lives for the brethren. Indeed, the sequela or imitatio Christi forms an immediate and powerful argument.

From the Fifth Crusade and following, the model sermons of James of Vitry, Odo of Chateauroux, and Humbert of the Romans are an elaboration on these themes, but they maintain the strictly scriptural reasoning. They are more subtle, more complex, and more focused on the spiritual struggle implied by taking up the cross. Here is a deeper theology, developing the notion of the crusade as a personal conformity to Christ, as a work of conversion of heart with the expectation of spiritual benefits. The liberation of the Church in the East and the reestablishment of the Christian people is still the rationale, but its ascetic and mystical import are now clearly in the forefront, with the hope of a heavenly kingdom predominating over the success in time of the Church Militant. The focus is more on the crusader than on the crusade.

James of Vitry was a master of Paris, deeply involved in the reform of the clergy as well as the domestic crusade against the Albigensians. He was made bishop of Acre and accompanied the Fifth Crusade to Damietta. Later, on his return to Europe, he was made cardinal-bishop of Tusculum.

In one sermon he expounds a text of the Apocalypse—itself based on the prophecy of Ezekiel about the “tau,” the cross, as the “sign of the living God.” The contrast between hearing the words of the preacher now and responding to them in due time versus neglecting them is dramatically presented: “Those who do not want to hear the gentle whisper of preaching, at least let them hear the great shout of the Crucified, otherwise they will hear the thunderclap of His terrifying voice: ‘Depart from me, you accursed!’”

It is precisely Christ crucified to whom the crusader is to be conformed, for He was the first crucesignatus. James poignantly compares Christ’s being signed with the cross by the soldiers’ nails and bearing the marks of the cross in the holy sepulcher with the “cross which is fixed to your cloaks with a soft thread.” Christ is in fact the true friend who, according to Solomon, will prove Himself in adversity; can the hearers of this sermon resist returning the favor? The contrast between the threat of the destructive angelic ministry and the judgment of the crucified Christ on the Last Day, on the one hand, and the touching presentation of the generous renunciation of Christ and His fellow cross-bearers who have become true friends, on the other, is incomparably grand but not merely rhetorical; it is grounded in the words of John the Divine and the wise King Solomon.

Odo of Chateauroux succeeded James of Vitry as cardinal-bishop of Tusculum, accompanying Saint Louis to the East as papal legatus a latere. He was a most prolific composer of sermons, perhaps the most prolific of the 13th century, leaving well over a thousand manuscript sermons in collections.

Odo offers us one of the few crusade sermons occasioned by a particular feast of the Church calendar—in this case, the Conversion of Saint Paul (January 25). The scriptural authority for the sermon is Matthew 19, understood in medieval moral theology as referring to the religious life under vows in a community, since the Apostles, on the testimony of Acts 2, had lived the common life. Here it is boldly applied to such laymen as would take up the cross, leaving everything to follow Christ. To accomplish this there must be a profound conversion of heart, akin to Saint Paul’s, a conversion to a pure, burning love effected by the Incarnation of the Son of God. Saint Paul teaches us to run so as to obtain (or to catch) the prize, and the prize is Christ Himself. The examples of Abraham, Peter, Jonathan, and Mathathias are given. The sermon is a magnificent, tender, virile composition.

Humbert of the Romans was master general of the Dominicans. He did not himself engage in the preaching of the crusade, but he directed the brethren in this apostolate and composed a manual for the instruction of preachers. These texts are little more than sketches for the preacher to amplify. Even so, the witness of the saints of the Old and New Testaments as narrated in the panegyric of Hebrews 11 is brought forward. The indulgence of the crusade is given as an eminent motivation to the listener.

This indulgence is far more ancient than it is ordinarily thought to be. Already in the years immediately preceding Clermont, it had been offered to those who would fight in the reconquest of Spain and Sicily. Much earlier still, in the ninth century, Pope John VIII had granted what modern interpreters accept as a true indulgence, given at the beginning of its medieval development. The bishops of the realm of Louis II, the Stammerer, had written the Pope asking about the fate of those who died fighting the Muslims. The Pope replies with authorities from Ezekiel (“In whatever hour a sinner shall be converted, I will remember his sins no longer”) and from Saint Luke’s Gospel (“This day thou shalt be with me in paradise”). The first plenary indulgence was offered by Christ Himself! The Pope continues, “We, by our Humility, in so far as it is right and needful, and by the intercession of Blessed Peter the Apostle whose power is to bind and loose in heaven and on earth, absolve the aforesaid [crusaders] and commend them to God in our prayers.”

No single aspect of the Crusades has had more impact on the development of theology and pastoral practice than the grant of the indulgence. The current discipline is its outgrowth through the various bulls of the crusade. These bulls, in turn, affected the manner in which indulgences and other privileges were granted in the rest of the Church, until the largesse given once only to the crusaders was extended to all. After the definitive victory of the Turks, the good work of the crusade was replaced by other good works: the giving of alms to the poor, or to seminarians, or for the ransom of Christian slaves from the Barbary pirates. The Church began to extend the indulgence to the building of bridges, hospitals, and hostels, as well as of places of worship. Even the Eastern Orthodox patriarchates under the Ottomans maintained the grant of indulgences into the 19th and 20th centuries, sending procurators (mostly into Russia and Rumania) to bestow commutations of penance on those who would donate for the upkeep of the holy places.

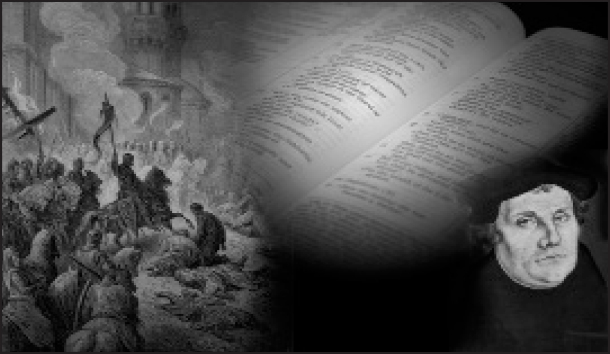

The doctrine of indulgences requires many of the principal dogmas of the Catholic religion to be distilled into concrete practice, and so it is not for nothing that Luther chose this as the locus for the inauguration of his dissent. Unless a man is deeply concerned with his own spiritual struggle and equally conscious of the Christian society into which he is incorporated by Baptism, he will not concern himself with indulgences, which are about temporal struggle in view of the Kingdom of Heaven. This is the very essence of the theological foundation of the Crusades, which shines on every page of Holy Writ. The Lutheran understanding of justification and its critique of indulgences is perhaps also a critique of a spiritual and temporal polity in which crusades could be justified and undertaken. This is another approach, which, like the Catholic one, claims to be resolved sola scriptura, for Luther bases himself on Isaiah 10 when he says that “To fight against the Turk is the same as resisting God, who visits our sin upon us with this rod of his anger.”

Leave a Reply