Comparing the 18th and 21st centuries

Many people believe our turbulent, anxious age is unique. A few years ago I created an art exhibit with the same title as this article, and became convinced that the century most akin to ours is the 18th, the so-called “Age of Reason and Enlightenment.”

There are uncanny similarities between the two centuries: fascination with scientific discoveries and rapid technological progress, emphasis on reason and intellectual discourse (recently, alas, that’s less robust), and right next to these themes, religious fanaticism, multiplying fringe cults, superstitions, irrationality, and violence.

So, the 18th century is as much the century of Diderot, Rousseau, Montesquieu, and Voltaire, as it is of Saint-Germain, Cagliostro, Mesmer, and, of course, Robespierre and the insanity of the Terror. All followed by endless wars.

And I see exactly the same phenomena in our time— many on the surface, others subterranean. But let’s examine them closely. In 1714 the Sun King died. Almost immediately everything changed. No more gloom, no more restrictions as during the king’s last years. Under the baton of the dissolute regent, Phillipe d’Orléans, people were dancing in front of what were merely painted backdrops; frivolous, titillating canvases of François Boucher, and of Jean-Honoré Fragonard, charming, and full of light. Life was a masquerade; hedonism the order of the day … and then the thump of the guillotine ended it all!

Did people feel it coming? Perhaps. The melancholy art of Jean-Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Lancret, the desperation in the writing of Novalis and in the paintings of Caspar Friedrich give us a hint. The merriment was on the surface, the anxiety underneath.

Our collective addiction to entertainments is as unbounded as it has ever been: the Internet, the thousands of electronic games, and hundreds of streaming TV programs. Most are artistically inept, intellectually shallow, and ideologically repugnant. That doesn’t matter, though, since they seem to keep people happy. But do they? We suffer from rampant crime, homelessness, drug overdoses, and suicides, especially among the young. And the guillotine, “morphed” into the shape of nuclear annhiliation and a looming Third World War, is creeping towards us from the fog. Again, merriment on the surface, desperation underneath.

I believe architecture is the “face” of society. Through their architecture, we know how the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, Romans, and the people of medieval times and the Renaissance viewed the world, how they perceived themselves. Today we are obsessed with architectural grandeur. The tallest building in the world, the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, spirals upward more than twice the height of the Empire State Building, 2,717 feet into the cloudless desert sky. I suspect many architects around the world are now planning a structure that will surpass the Burj Khalifa. After all, contemporary technology enables them to build practically anything they envision.

The architects of the 18th century didn’t have that luxury, but their projects were no less ambitious. What they couldn’t build in reality, they “built” on paper. A telling example lies in the work of Étienne-Louis Boullée, born in 1728. He studied under Jaques-François Blondel, designed a few houses in Paris, and at age 34 was accepted into the Academy of Architecture. There he began attacking Rococo, the prevailing style of the time, patronized by Madame de Pompadour, the King’s charming and bright mistress. Boullée made a lot of enemies. He was a small man, high-strung, impatient, and difficult. At age 46 he retired from practice and devoted his time to drawing and teaching.

He believed Utopia attainable. He also believed architecture was the means to attain it. And he set out to create on paper an ideal architetural environment—a string of buildings, which, according to him, were to be but basic geometric shapes—cube, cone, pyramid, parallelepiped, square—blown up to a Cyclopean scale.

Since his heart was set on serving humanity (he rather despised individuals) he concentrated on public edifices: a Monument to Reason—a steep, unadorned pyramid, its tip piercing the clouds; the Palace of Justice—a massive, windowless, stone parallelepiped 1,500 feet long; a Stadium—a monstrosity over half a mile in diameter and 400 feet high, garnished at the top with a monotonous row of hundreds of columns.

The obsession with grandeur was as relevant to the 18th century as it is to the 21st. For Boullée, man as “the measure of all things” was no more. In his rendered fantasies man is but an insect lost in front of some monstrous state edifice. Robespierre liked Boullée’s ideas. But not one of his Cyclopean projects was ever realized. It would be technically challenging to build them even now.

The 18th century was also remarkable for the sheer number of technological inventions—the steam engine and steam ship; the marine chronometer to measure longitude; the sextant; ball bearings; the volt battery; the Fahrenheit thermometer; vaccination for small pox; bifocal eyeglasses; jars for preserving food; the first English dictionary; the piano … The list is endless, with some inventions that helped to change civilization, while some just made life more pleasant and comfortable.

In France there was the invention of the modern encyclopedia, based on the idea that all human knowledge in all fields could be collected and summarized—from philosophy and theology to science and the arts, there would be volumes of knowledge, based exclusively on human reason. Even the existence of God could be accepted only with definitive scientific proof.

The Encyclopédie was a colossal undertaking. Between 1751 and 1772, 28 volumes were published, consisting of over 70,000 articles and more than 3,000 engraved illustrations. As Denis Diderot, the chief editor of the Encyclopédie, put it, “our goal is to change the way people think.”

That aim was no less grand than Boullée’s projects, but while Boullée couldn’t realize his visions, the Encyclopédieists did. The Encyclopédie became the hottest topic of the day, animatedly discussed in salons, and patronized by Madame de Pompadour.

But the fundamental tenets of the Encyclopédie—reason, rational discourse, and rigorous scientific examination—were vigoriously challenged by their exact opposites—irrationality, fascination with spiritualism and the supernatural, divination, and black magic—which also thrived during the 18th century. The most prominent practitioners of these were Comte de Saint-Germain, Franz Mesmer and Cagliostro.

The exact origin of Saint-Germain is still unknown. Some said he was of a humble origin, born in Strasbourg at the very end of the 17th century; others that he was a Spanish Jesuit; still others that he was born in Savoy, the illegitimate offspring of an Italian princess and a tax collector.

He had a striking appearance: extremely pale, with dark hair, a dark pointed beard, and a penetrating gaze. He was exquisitely dressed. He loved jewelry. His adherents believed that he possessed the secrets of the universe, the powers of telepathy and levitation, and that he could even walk through walls.

He traveled all over Europe and enjoyed the patronage of many great princes. Gazing intently into the eyes of his interlocutors, he would say that he was 3,000 years old, had met Helen of Troy, had been reincarnated in the seventh century B.C. as Hesiod—and thus had a direct connection to Greek mysticism and cosmology—and then, in the 16th century had been the great Francis Bacon, philosopher and proponent of “natural magic.”

When performing his magic rituals, Saint-Germain would wear a suit of golden chainmail he claimed once belonged to a Roman emperor. Over it, he wore a purple cloak clasped by a seven-pointed star with diamonds and amethysts.

When he died in Schleswig, Germany, in 1784, in the palace of his patron, Prince Charles of Hesse-Kassel, his adherents did not believe he had died. They asserted he had pulled a similar trick before as Francis Bacon: faking his death on Easter of 1626 and even attending his own funeral in disguise. After that, supposedly he traveled to Transylvania, where he secretly practiced his magic, attained immortality, and came back to the world as Comte de Saint-Germain.

No less remarkable was the life of Giuseppe Balsamo, known as Cagliostro. He was born in Sicily in 1743. From an early age he was interested in the occult and the supernatural. He was a fast learner and a trickster. When he was 24, he convinced a goldsmith that through magic he had learned the location of a hidden treasure, which he offered to reveal for a substantial amount of money. The gullible man agreed. There was no hidden treasure though, and it was the last the goldsmith saw of his money and of Cagliostro, who escaped to Rome.

There Cagliostro married a 17-year-old girl, eight years his junior from a prosperous family. In Rome he befriended a certain Agliata, a forger and a swindler, who, in exchange for sexual favors from Cagliostro’s young wife, taught him his craft of forging private letters, diplomas, marriage certificates, and all sorts of official documents. His wife was not happy, but agreed.

Soon after, the couple went to London, where Cagliostro became a disciple of Haim Falk, a well-known miracle healer, who taught him alchemy, the Kabbala, and various magic rituals. It was there Cagliostro adopted his mystic persona and alias.

From that time on, Cagliostro’s reputation accelerated with incredible speed. He was now known as “the Magician” and was invited to royal courts to perform occult mysteries. He would chant loudly, or whisper the names of angels and spirits, both good and evil. He performed exorcisms and claimed the ability to cure all illnesses though he had never studied medicine. He deciphered dreams, invoked protections from misfortunes, including the “evil eye,” and blessed those who sought his powers.

He was revered! A hundred years later, the collective delusion that made Cagliostro’s reputation was depicted by Hans Christian Andersen in his immortal masterpiece folktale, “The Emperor’s New Clothes.”

Cagliostro’s glory, however, came crashing to an end as swift as his ascent. While in Paris, he was suspected of taking part in the infamous Affair of the Diamond Necklace, a swindle in which Queen Marie Antoinette’s signature was forged to a purchase order for an expensive diamond necklace, for which she then refused to pay. He was thrown into the Bastille and held for nine months.

He was eventually acquitted, but his reputation was in tatters. Unable to remain in France, the Cagliostros went to Rome, where the wife (perhaps, remembering how her husband had “sold” her to the forger) is said to have denounced him to the Inquisition. He was arrested, imprisoned in the notorious Castel Sant’Angelo and sentenced to death. Though his sentence was later commuted to life in prison, he died within six years, in 1795.

Then, there was Franz Mesmer, a German physician born in 1739, and from whom we have the word “mesmerize.” He was fascinated with music and astrology—his dissertation was called “On the Influence of Planets on the Human Body and its Diseases.”

Mesmer believed he had discovered what he called “animal magnetism,” or the constant flow of energy between animate and inanimate objects. According to his theory, knowledge about how to control this flow is the key in healing all ailments of the human body, including restoring vision to the blind.

Mesmer considered himself the ultimate channeler of this energy. During treatment, he would sit in front of his patient, his knees touching theirs. Then, looking intently into the sick person’s face, Mesmer would press the latter’s thumbs with his hands. Sometimes he’d move his palms down the patient’s arms, or press his hands onto the patient’s hypochondrium. He believed that by these manipulations he was guiding the flow of animal magnetism throughout the valetudinarian’s body. He would conclude the treatment by playing music on a glass harmonica.

After achieving considerable success in Vienna, he moved to Paris and settled in the most expensive part of the city. Soon he had more patients than he could handle.

And yet, in spite of all of our scientific discoveries and technological advances, and all the powerful voices denouncing the mysterious and the supernatural, the forces of the occult are on the rise.

In 1784 King Louis XVI, appointed a commission from the Royal Academy of Science to investigate the authenticity of animal magnetism. The commission consisted of the American Ambassador to France Benjamin Franklin, the astronomer Jean Bailly, the distinguished chemist Antoine Lavoisier, and Doctor Joseph Guillotin. Guillotin was the inventor of the device that bears his name, which was applied 10 years later to the neck of his fellow commissioner Lavoisier, during the French Revolution.

The commission concluded there was no evidence of some mysterious energy circulating within the human body, as Mesmer claimed. Despite the commission’s finding, Mesmer remained enormously popular. Many considered him a genius. His stature as a celebrity, along with that of Saint-Germain and Cagliostro, was on par with the Encyclopédieists.

Thus, one is tempted to conclude that the enlightened 18th century was as much the Age of Anti-Reason as it was of Reason.

Now to our time—the century twenty-one—and to our inventions and our discoveries. We point telescopes at the universe and see black holes, terrifyingly sucking in everything—including light—to the point of no return. We see how galaxies looked millions of light years ago, and contemplate the incomprehensibly immense spaces between them—spaces oddly proportional to those between microscopic individual atoms. (If we imagine an atom enlarged to the size of a fly, it would be in the middle of an empty stadium and the atom closest to it would be a fly in the middle of another empty stadium.)

We see how the macrocosm and microcosm mirror one another, and we have unpuzzled many secrets of both. We adjust the theories of Einstein to quantum mechanics. We have mastered the transplanting of human organs to the point that it has become almost a routine procedure. Our achievements in artificial intelligence are mind-blowing. And we proudly question the existence of the Creator.

Christopher Hitchens, author and journalist, is regarded as one of the most influential atheists of the 20th and 21st centuries. With wit and eloquence, he called for the New Enlightenment, free of all religions! Enlightenment based exclusively on reason. He coined the famous dictum known as Hitchens’ Razor: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”

Hitchens’ words are echoed by another prominent atheist, Richard Dawkins, a famous evolutionary biologist. In his bestselling book The God Delusion he stated with utmost certainty that God does not exist and called belief in Him one of the greatest evils!

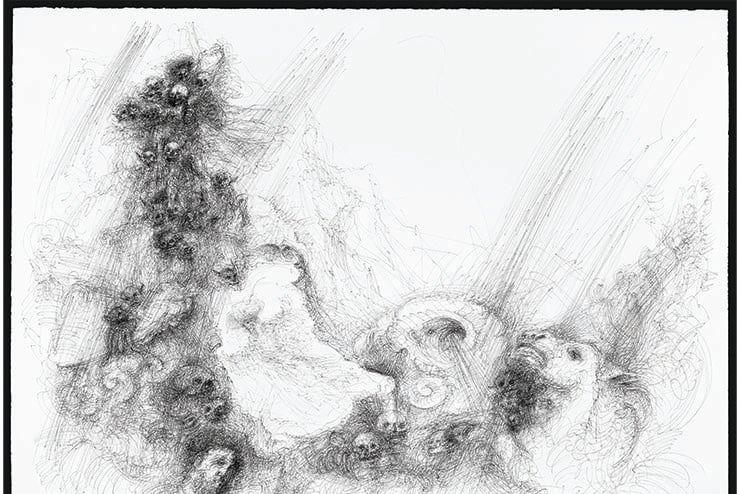

And yet, in spite of all our scientific discoveries and technological advances, and all the powerful voices denouncing the mysterious and the supernatural, the forces of the occult are on the rise. Astrology, spiritualism, religious cults (and fanatics!) are still very much around, in everything from the the relatively harmless reading of Tarot cards and horoscopes, to the practice of black magic and the worship of Lucifer.

One wonders, why? Could it be that even with all the sophisticated technology with which people are wasting a great deal of their time, and all the disillusionment with organized religion, people still have a spiritual itch that is not being scratched? Somewhere, implanted in their very core, almost in their DNA, they have an insatiable thirst for finding out whether there is another world, and understanding that mysterious beyond to which everyone eventually goes.

Will there be nothing? Or will there be individual souls (even people who aren’t sure seem inclined to believe in souls) driven by cosmic wind, circling forever in the dark, freezing universe, among myriad other souls?

Of course, in time, each of us will find out for ourselves what there is after death, but many want to know now, while they’re still in this world, using their five senses, however limited. And, perhaps, this undercurrent of thirst is as intense in the 21st century as it was in the 18th? After all, our life is but a short stretch between two voids—the void we came from and the void into which each of us returns. No one knows how long his or her stretch between the two voids is going to last, but even the longest one is but a blink in time. And it seems that while we are on our brief journey in this world, there is an impenetrable wall, blocking us from that ultimate void.

Anton Chekhov once said that “Lice consume grass, rust consumes iron, and lying the soul!” To expand upon Chekhov’s words, we could say, lying consumes not just individual souls, but the collective soul of society. And it does so faster and more efficiently than weapons of war. Bombed-out buildings and destroyed infrastructure rather rapidly can be rebuilt (Germany and Japan after World War II are proof of that). But destroyed souls take generations to heal.

The “Magnificent Revolution” erupted in France in 1789 as a nobles’ rebellion about taxation against a weak king, and rapidly deteriorated into an all-encompassing bloodbath under the slogan of “Equality, Liberty, and Fraternity.”

But there was no equality. In the 1790s when Parisians were starving, Revolutionary Minister of Justice Georges Danton, sitting with his comrades in a fancy restaurant (there were a few still left in Paris), stated grandly, “Now it is our turn to consume fancy food!”

The revolutionaries sought to create “une nouvelle race”—a new, revolutionary race. To remake the people, the revolutionary parlementarian Boissy d’Anglas proclaimed the State the monitor of all individual activities, “including one’s inner and private behavior.” A Frenchman could no longer address someone as monsieur or madame, but only as a fellow “citizen.”

“The Republic is the eradication of everything that opposes it!” declared Robespierre. Hanriot, Commander of the National Guard, wanted to burn the Bibliotheque Nationale. “We will burn all the libraries,” he declared, “for only the history of the Revolution and the [revolutionary] laws will be needed!”

Even the dead were not spared—the magnificent tombs of the Basilica of Saint-Denis were smashed to pieces, the coffins opened, and the bones sold as souvenirs.

There was no liberty either. Memos and protocols of the Revolutionary Tribunals read like excerpts from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s The Gulag Archipelago.

A man named Brille was guillotined for having wrapped a pound of butter in the revoluiontary government’s newly issued paper money, thus “showing disrespect for the Revolution.” Antoine Brasseur, a clockmaker, was guillotined for “being arrogant … and speaking ironically about the revolutionaries.” And Lemaire, a baker, for his remark that “one day all these ‘patriots’ will be eaten by lice.”

Chassaut, a former priest-turned-educator, wrote of the time that children were obliged to denounce their parents’ deviations from the revolutionary road. They were started young, and taught to see political meaning everywhere. A house of cards was but a symbol of the oppressors’ châteaux, swept away by the new regime; a high-flying kite symbolized a citizen, enjoying new freedom. Even the new revolutionary patriotic candies had “lessons in citizenship” printed on their wrappers.

The revolutionaries blamed shortages and misery on “the enemies of the people.” These enemies, according to a popular orator from the Paris Commune, were “all the merchants … bankers, pettifoggers and anyone who has something.”

Having “something” could mean having culture, education, and decent clothing, or simply being born with a refined appearance or well-groomed hair. “To keep one’s head on one’s shoulders it was advisable that it were unkempt,” wrote a contemporary observer. A deputy of the National Convention and colleagueof the unfortunate Lavoisier, Antoine-François de Fourcroy, recalled that “it was enough to have some knowledge, to be a man of letters, in order to be arrested.”

The whole concept of liberty, equality and fraternity in the last two decades of the 18th century was as much based on a lie as it is in the first two decades of the 21st. A lie, as Beaumarchais brilliantly put it in his play “The Marriage of Figaro” is:

at first a mere breath, skimming the ground like a swallow, but sowing poison as it flies. It takes root, creeps up, makes its way, goes from mouth to mouth; then, all of a sudden, one knows not how, is standing upright, rearing its head, hissing, swelling, growing visibly. It spreads its wings, takes flight, eddies round, bursts, thunders, crashes, and becomes, thanks to heaven, a general outcry, a public crescendo, a universal chorus of hatred and prescription. What devil could resist it?

Or as Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels said succinctly, ”Repeat a lie ten times and people will believe it is the truth.” Sound familiar?

Leave a Reply