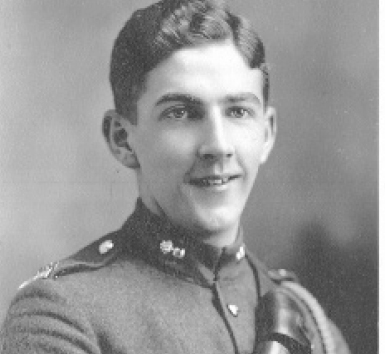

William Ball was just shy of 19 and living in the town of Souris on the prairies of Canada when war erupted in Europe in August 1914. The region was still something of a frontier, devoted to trapping and trading with Indians, and inhabited by hearty, adventurous types, Ball among them. On a bet, he and a friend had spent the winter of 1913-14 in a tent on the banks of the Souris River. Temperatures dropped to 40 below and the river froze solid, but the young lads persevered. With the coming of spring, they hiked triumphantly back to town and collected more money than they had ever seen at one time in their young lives.

By 1915 Ball was a member of the 12th Manitoba Dragoons, a likely choice for someone good with horses. After months of hard training the unit was ready for overseas deployment, first for staging in England and then for the battlefields of France and Belgium. To celebrate, the horsemen played a football game. The tall, raw-boned Ball went down with a broken ankle. He was asked to resign from the dragoons so another volunteer could take his place. He reluctantly did so, spending several months recuperating and cursing his luck—he was afraid the war would be over by the time he could re-enlist.

Early in February 1916 he joined the 37th Overseas Battery, Canadian Field Artillery. It didn’t have the élan of the dragoons but it would give him a chance to get to the battlefront. The unit would become part of the 10th Brigade, 3rd Canadian Divisional Artillery. The brigade was typical of Canadian units. Two thirds of its men were born in England, Scotland, or Ireland. Another four percent were born in the United States. Only 28 percent were born in Canada. Canada was still a country of immigrants, especially in the Western provinces.

When the 10th took up positions at Ypres in Belgium during the summer of 1916, Ball began keeping a war diary. His initial entries are often filled with wry humor and a certain affection for his German counterparts. While British and French propaganda referred to the Germans as Huns or Boche, Ball calls the enemy Fritz.

Ball was already having close calls.

Back for a rest, have been up at the front for one month and spent much time, nights in the trenches. Was there every third day for a shift of 24 hours, on the telephone. The dugout was one made by Fritz, our telephone suspended on a bayonet, our seat a grey German coat. This was in Sanctuary Woods within the Ypres salient. Had many exciting times on our way owing to snipers. Came back last night to find that Fritz had got two direct hits right on our battery.

A day later, his luck held.

Three of us were sitting outside the hut tonight. I was sitting nearest the trenches, it was dusk. A shot came down, hitting the fellow in the center sitting 2 feet away or less and talking to his mate on the other side. The shot penetrated his neck and came out his mouth, after having whipped past me. I just missed it by a fraction. . . . My number is not up yet evidently.

The next day, more of the same.

Fritz has been putting shrapnel all around the house, or what is left of the house. While cooking my dinner one burst just above the door. I have had enough excitement for a few days. I was relieved tonight. Had trouble getting away with enemy balloons and airships around. We had to keep still for fear of giving away position.

Day after day, Ball records casualties and reports of rain and knee-deep mud. A rumor has it that his outfit will be pulled out of the Ypres Salient and sent south to the Somme. “This will be an eventful happening,” says Ball, “as Canadians stood their ground in this place and have held it since.” The Battle of the Somme was horrifically bloody. On the first day, July 1, 1916, British generals launched a series of assaults into withering German artillery and machine-gun fire. British troops fell by the thousands. By the time the day was over, more than 57,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers were killed, wounded, or missing. The battle would continue, sporadically, until November 18. By then, Germany had suffered 500,000 casualties; France, 200,000; and Britain, 420,000. Of the British casualties, 27,000 were Canadians; 23,000 Australians; 7,400 New Zealanders; and 3,000 South Africans. A German officer, Friedrich Steinbrecher, wrote, “Somme. The whole history of the world cannot contain a more ghastly word.”

Ball arrived on the battlefront at the Somme on October 11. The next day, the CO of the 37th, Capt. W.B. Shaw, was badly wounded, and an enlisted man, John Henry Austin, was killed. Harry, as Austin was known to Ball, was an attorney from Victoria, British Columbia, when he enlisted in January 1916 at 41 years old. In 1914 his age would have disqualified him, but by 1916, with Canadian ranks depleted, he was welcomed. Major George Purves, the CO of another Canadian artillery battery, the 43rd, was also killed. The Scottish-born Purves was a rancher in Alberta when war came. “This is by no means a health resort,” said Ball. The next day one of his best friends, Alex Collins, was severely wounded. A package from Dolly Nicholls and another from Flo McGuire helped to boost Ball’s morale, though.

Lasting for three weeks in late October and early November, the battle for the Regina Trench was particularly bloody. The Canadians were in the thick of it, and Ball had his first contact with large numbers of German prisoners. “Some fine fellows amongst them,” he commented. The battle seesawed, and it was not until November 11 that the Regina Trench was firmly in Canadian hands. By then Canadian units had suffered 24,000 casualties. Ball was beginning to look upon those friends who got a “Blighty”—a wound bad enough to have them evacuated to England but not prove fatal—as lucky. “Some war, this,” he concluded one diary entry. “I shall be glad when it is over.”

Ball carefully recorded all those in the 37th who died, as if creating a record for their loved ones. He was particularly moved by the death of Capt. Walter Turnbull. “Our best officer,” said Ball.

The battery as a whole are feeling mighty blue. I went up and helped carry him home. Poor lad, he was a man, and a gentleman. Our favorite. The boys thought the world of him and would do anything for him. . . . I wish I could bring him to life. He was Winnipeg’s most favorite hockey player, and now see what one bullet has done for this fine athlete. . . . He was afraid of nothing. Hope to meet him when the bugle sounds and we all congregate in our eternal home once again. Goodbye brave man, thou art Nulli Secundus.

The Turnbull Cup, presented to champions of the Manitoba Junior Hockey League, is named for him.

On December 2, the Canadians arrived at a new position along the front in northwestern France and looked up at a German-held escarpment. “I think it is called Vimy Ridge,” noted Ball. Little did he know that the battle for the ridge would bathe the Canadians in glory and result in their greatest military victory, not only in World War I but in any war.

The Germans had seized control of the four-mile-long ridge in October 1914. With typical German thoroughness they dug caves, tunnels, and trenches, built concrete bunkers and machine-gun emplacements, and positioned artillery pieces on the reverse side of the slope. French and British attempts to storm the heavily fortified ridge failed. The French alone suffered 150,000 casualties.

Now the Canadians were tasked with taking the ridge—and it was the first time all four  divisions of the Canadian Corps were serving together. Nonetheless, the commanding general of the operation was a British lieutenant general, Julian Byng. He had none of the arrogance or pomposity of many of his fellow British commanders, though, and was unorthodox, innovative, and flexible. Most of all, he was determined that this operation not be another bloodbath like the Somme. Second in command was a Canadian major general, Arthur Currie. Byng tasked Currie with analyzing the Battle of the Somme and then applying lessons learned to an assault on Vimy Ridge. Currie was conscientious and methodical, and studied not only the Somme but Verdun. He questioned both French and British officers who had served in both battles until, as one officer put it, “he pumped everyone dry.” He read dozens of reports and grasped both the big picture and the smallest details.

divisions of the Canadian Corps were serving together. Nonetheless, the commanding general of the operation was a British lieutenant general, Julian Byng. He had none of the arrogance or pomposity of many of his fellow British commanders, though, and was unorthodox, innovative, and flexible. Most of all, he was determined that this operation not be another bloodbath like the Somme. Second in command was a Canadian major general, Arthur Currie. Byng tasked Currie with analyzing the Battle of the Somme and then applying lessons learned to an assault on Vimy Ridge. Currie was conscientious and methodical, and studied not only the Somme but Verdun. He questioned both French and British officers who had served in both battles until, as one officer put it, “he pumped everyone dry.” He read dozens of reports and grasped both the big picture and the smallest details.

Byng and Currie determined that every man know the battle plan for Vimy, the jobs of those around him, and his own job exactly. Detailed maps were distributed to the troops. Only the date for the operation would be withheld from the men. The generals also determined that no operation would be launched until intelligence, and more intelligence, had been gathered and thoroughly analyzed. This meant continual probing of the German lines and regular reconnaissance missions, on the ground and in the air. The strength and nature of every German position would be known. Finally, the men would be rigorously trained, emphasizing timing and coordination. Assaults were rehearsed, again and again, against mock-ups of the German fortifications. The infantry would always be supported by artillery, which would direct fire at specific targets. The command style of Byng and Currie left the troops feeling respected and valued, and they, in turn, gave their all for their commanders.

On December 7, Ball recorded, “Our boys made a raid on Fritz. Quite successfully with very few casualties. This was about 4:50 a.m.” The probing of German lines and intelligence gathering had begun. Day after day, Ball notes that infantrymen were conducting nighttime raids. These raids were meticulously timed and executed with precision. From December 1916 through March 1917, Canadians raided German positions 55 times, bringing back critical intelligence—and wreaking havoc with German slumber. “These infantry boys are good fellows,” said Ball. “The more I see of them the better I like them. This Battalion, the 43rd, were badly cut up in the Somme, going in 600 strong and coming out 65 strong.”

Ball’s artillery battery, like the other artillery batteries, was sending daily salvos into the German positions on Vimy Ridge. The salvos didn’t kill many Germans but kept the Germans busy repairing fortifications. The salvos also kept the Germans sleep deprived and wore them down physically and emotionally. When weather permitted, airplanes strafed and bombed German positions. “As I sit here and see the numerous aeroplanes skimming through the blue sky, so perfectly governed, it makes me realize what a great age this is and what a big adventure we are engaged in,” said Ball from a forward-observation post on a clear January day. “The guns are booming, the heavies are going over behind us, sounding just like an express train.”

The men suffered through a severe winter. Nearly all were intermittently ill. Many had sores and boils covering their skin. Finally, on April 5, 1917, Ball noted,

The first fine day. We have been having awful weather. Snow storms, etc, cold all the time. We appreciate this. You note a marked difference in the spirits of the boys already and we are now making attempts to clean our tent out, which is plastered in wet mud. Big preparations are going on. There will be something doing in a few days.

Included in the “big preparations” was a relentless bombardment of Vimy Ridge. During the week leading up to the assault, the Canadian artillery batteries pounded German positions with 50,000 tons of high explosives. The Germans called it the “Week of Suffering.” The bombardment not only kept the Germans huddled deep in their fortifications but prevented supplies and reinforcements from arriving. It also kept the Germans on high alert. Several times the artillery staged feints, beginning with creeping barrages following by a sudden intensification as if an assault were about to commence. On these occasions, German infantrymen were ordered to prepare to repel an assault—which didn’t materialize. Exhausted by repeating the futile exercise again and again, and by the bombardment, they were spent by the time the actual assault came.

Meanwhile, German artillery was responding in kind. On April 8, Easter Sunday, Ball records heavy shelling of his position.

Just now Fritz dropped two or three to the right and left of the door of our dugout, just a matter of yards, and he would have hit the ammunitions dump, which is just outside our door—about ten yards. Another now right in front of our dugout, filling the place with smoke and smell of powder. This is getting warm. I trust he will quit. It is the nearest I have ever experienced in a dugout. Every shot now is only a matter of yards. The size of the shells I believe is 5.9. They make a rather large hole, too big for my liking. We are now in a trench to the flank of the guns. Driven out by Fritz. He is getting direct hits. Killed a man just now. Wounded many. A Fritz aeroplane was brought down just now. It was a good sight, a little revenge at last. This is the worst bombardment yet. I hope our heavies get the battery that is doing the damage. Sergt. Moffatt had part of his face blown away just now. Some Easter. It has been one awful day. Moffatt, Davidson, Myers, Church and two or three others are away wounded and two killed, Bert Whitehead and Longworthy. I knew Bert quite well. We had a great trip together while in Blighty. The Sergt of D Sub is totally deaf and another shell shocked. Believe me, enough for one day. We had to leave the guns, shelled out four times. Got many direct hits.

Word was passed that night that the assault would go before dawn the next day, Easter Monday. Men tried to sleep, but most found it impossible, especially those in the infantry. F.C. Bagshaw of the 5th Battalion from Saskatchewan was one of those. It was well past midnight, and he was wide awake. From several yards away he heard his good friend, Dave McCabe, call to him, “Bag, I’ll tell you what we’ll do. I’ll recite Robbie Burns and you recite Shakespeare.” In the dead, still night they began, and continued for three hours while their comrades in the 5th listened.

At 5:30 in the morning, with snow falling, General Byng launched the assault. It began with a thunderous, creeping barrage. The Germans initially thought it was another feint. This time, however, 20,000 Canadian infantrymen followed close behind the line of explosions. By doing so they were able to capture some enemy positions before the hunkered-down Germans could respond. At times, the fighting was ferocious. Canadian officers went down, but noncoms quickly took command. Sergeants were killed, but corporals filled the gaps. The highest point on the ridge, Hill 145, was captured by the Canadians with a sudden bayonet charge against machine guns. Timing, coordination, discipline, and bravery were evident everywhere.

So many Germans were captured on the first day of the battle that the Canadians couldn’t spare troops to guard them all. The Canadians finally began sending German prisoners unescorted to the Canadian lines. This proved fortunate for Pvt. Charles Dale. In the initial assault, the explosion of a German artillery shell had blown him through the air and shattered his thigh. He had lain helpless for six hours in the snow and cold when an unescorted German prisoner happened by. The German hoisted Dale from the ground and carried him to a Canadian “dressing station,” saving his life.

On April 11, Ball declared, “We are still taking in more ground. Vimy is in our hands.” He was mostly right, but a wooded knoll, called the Pimple, at the extreme northwestern end of the ridge remained in German hands. On the morning of April 12, Canadian infantrymen, obscured by blowing snow, charged the Pimple and took German fortifications, including several machine-gun emplacements, by surprise. The four-mile-long ridge was now entirely in Canadian hands.

Taking Vimy Ridge cost the lives of 3,600 Canadians. Another 7,000 were wounded. Four Canadians would receive the Victoria Cross, two of them posthumously. One of the two who survived the battle would be killed two months later. After several failed French and British attempts at taking the ridge, the stunning victory of the Canadians, all fighting together for the first time, was a sensation. “In those few minutes,” said Brig. Gen. Alexander Ross, “I witnessed the birth of a nation.”

Scottish-born Frank Worthington had been in Canada less than two weeks when he enlisted. “I never felt like a Canadian until Vimy,” he declared. “After that I was a Canadian all the way.”

The aftermath of the battle was a scene of gore and devastation. “Have been all over Fritz’s old land, past Vimy and Railway Embankment,” recorded Ball on April 14.

There are all kinds of dead still lying around, every inch is torn up by shellfire. . . . Procurement of many souvenirs and have already given many away. We were very tired. They are busy all over carrying dead. I saw some rotten sights; one particular thing was a horse with its head blown clean away from its shoulder and Fritz in a similar state.

The war continued for Ball and his fellow veterans of Vimy. Only a disabling wound or death would take them out of the conflict. And Ball records plenty of both. In the week following Vimy, Van Cooten, Johnson, and Whittaker were killed, and Carpenter and Ferguson were badly wounded. And so it went, day after day, week after week.

Overhead, Ball watched aerial battles that later became fodder for Hollywood. This was “Bloody April” of 1917. “Great air activity,” noted Ball on April 25. “Two planes brought down by the famous ‘Red’ of the Germans. Our planes had no chance, as they were just observing planes. It occurred right overhead. One came down in flames.” The German pilot was Manfred von Richthofen, the Red Baron, who would score 80 kills during the war, making him the war’s leading ace.

Ball would continue fighting in the thick of the war until the bitter end. By then, he was one of only a handful in his battery left alive and not badly wounded. He arrived in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in March 1919 and saw what was left of the port after the devastating explosion of an ammunition ship in December 1918 that killed 2,000 people. By April, he was back in western Canada and again a civilian—“THE GREAT DAY,” he called it in his diary.

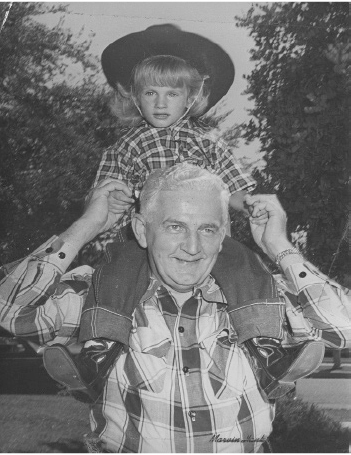

William Ball spent some time in Saskatchewan and Alberta, but soon worked his way to California. He would eventually build a house on several acres overlooking Zuma Beach in Malibu. It was the first house in the area. One of his sons, Don, the father of my wife, Susan, built a house on adjoining acreage. When the house was complete, Bill gave Don a bell, a souvenir that came from the ruins of a church that, before its destruction in the war, stood facing Vimy Ridge. “Bells are made to be rung,” declared Bill. “Use this to call the children in from the fields for dinner.” Don hung the bell from the eaves at the corner of the house. And every evening, Susan and her five brothers and sisters heard the ringing of the bell, not knowing all it meant to their grandfather.

California. He would eventually build a house on several acres overlooking Zuma Beach in Malibu. It was the first house in the area. One of his sons, Don, the father of my wife, Susan, built a house on adjoining acreage. When the house was complete, Bill gave Don a bell, a souvenir that came from the ruins of a church that, before its destruction in the war, stood facing Vimy Ridge. “Bells are made to be rung,” declared Bill. “Use this to call the children in from the fields for dinner.” Don hung the bell from the eaves at the corner of the house. And every evening, Susan and her five brothers and sisters heard the ringing of the bell, not knowing all it meant to their grandfather.

[William Ball’s diary, The Long Sadness, transcribed and annotated by Susan McGrath, has been published by Seanachie Press. It is available at Amazon.com.]

Leave a Reply