Last September, in a speech about Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, President Bush used for the first time a phrase that has come to signify his foreign policy objectives and his vision of the post-Cold War age: “New World Order.” Here and in subsequent speeches the President would hint that, with the liberation of Eastern Europe, the end of the Cold War, and the crumbling of Marxist-Leninist ideology, the world in general and the United States in particular have reached a juncture in history of monumental importance, a point when the “ground rules” could be laid for a new and more just international order with America paving the way and setting the example by doing “the hard work of freedom.” The Persian Gulf War was the first “hard work” of the New World Order.

Bush’s vision of the future and conception of the new order have not gone unchallenged, even among Beltway pundits and politicians. The New Republic‘s Charles Krauthammer, for example, castigated President Bush last May for failing to bring the new order into sharp focus. The President had failed to find that catchy, memorable slogan or phrase that could serve as the principle around which the American people could rally, as when “Wilson invoked self-determination; FDR, Truman, and Kennedy, freedom; Carter, human rights; Reagan, democracy and democratic revolution.” He argued that Bush’s emphasis on keeping “the dangers of disorder at bay” was “too weak and passive an idea to deal with the crises of the post-Cold War world.”

Mr. Krauthammer suggested that Bush adopt the idea of “sub-sovereignty,” a concept the United States could use to lead the world to “a new world order that not just enforces rules but breaks old rules and makes new ones.” Though it is difficult to imagine Americans fighting “to make the world safe for sub-sovereignty,” Mr. Krauthammer believes this is the principle that could rally the country for a new world mission while satisfying “national groups seeking independence without fracturing the world.” Simply put, he argues that it is possible for the United States to rewrite international law, if not remake the world in our own image, while at the same time remaining on the right, “correct” side of history. Mr. Krauthammer assumes (like many of his colleagues) that his readers understand how the possible disintegration of such multinational states as Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union constitutes a crisis for the people of these countries and regions as well as for the denizens of Boise and Des Moines. His argument is also indicative of the underlying premise of the entire new order: that it is not enough merely to believe in the right of self-determination or secession, for in the New World Order citizens have lost their liberty and independence and are now duty-bound to act transnationally on their convictions.

Senator Orrin Hatch registered his review of the New World Order’s first year in a May editorial in the Wall Street Journal. The senator complained that Bush’s conception of the new order has thus far failed to encompass enough, as in failing to set a “coherent political and military strategy to achieve the goal of national self-determination for Afghanistan.” And why should the United States want to meddle in Afghan affairs? The Afghans have “suffered more than the Kuwaitis and the Kurds combined.”

Ah, there’s the rub. Whether consciously or unconsciously, Senator Hatch had succeeded in uncovering the true significance of the Persian Gulf War: it is the precedent for all future U.S. action on behalf of the New World Order and the standard against which all future action will be judged. In other words, the United States is now morally obligated to come to the aid of any people whose crisis or misfortune, historical suffering or oppression is greater than the sum total of misery endured by the Kurds and Kuwaitis. Or as Senator Hatch put it, by not increasing our aid to the Afghan resistance, the United States runs “the risk of developing a moral tunnel vision that blinds us to the tragic fate of another people.”

President Bush, however, is getting a bum rap. Despite the lamentations of Messrs. Krauthammer and Hatch, the New World Order is in excellent health. Look at the ever-expanding role of our military in world affairs and the varied hats our soldiers have worn since the Persian Gulf War began: they were the Defenders of Saudi Arabia, the Liberators of Kuwait, the Conquerors of Iraq, the Protectors of the”Kurds, and even the Saviors of the Bangladeshis. And with Addis Ababa teetering on collapse, Indian democracy wallowing in blood, self-immolations smoldering in Seoul, and tanks ready to roll into Croatia and Slovenia, the opportunities for additional American military action abroad in the near future are endless.

There is virtually no job the American military will not now do on behalf of the New World Order. Once upon a time we thought an army was necessary to protect the homeland and deter aggressors; we were once even wary of the domestic repercussions of a standing army. America’s New Armed Services of the New World Order, however, are busy abroad building villages, digging wells, clearing roads, distributing food, healing the sick, and policing the borders of countries thousands of miles away. Our military has upgraded its job description and will now be not merely a fighting force for hire, but will be all things to all people, a kind of armed synthesis of Oxfam, the Peace Gorps, and the Salvation Army. It has, in essence, become the world’s first international 911—with a switchboard in Washington and Uncle Sam as the dispatcher. Messrs. Krauthammer and Hatch underestimate how hard our military is working “to be all it can be.”

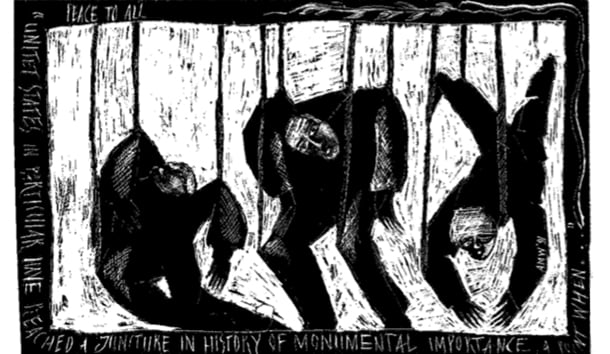

But there is a sounder, more visible indicator that the New World Order is right on track, and it is found in the form of nonverbal communication. In this age of media there is always a photograph or image that captures a significant historical moment and conveys its meaning more powerfully than words could ever do. The horrifying photograph of the Vietnamese child running and screaming in agony from the burning terror of napalm captured for a nation, for good or ill, the tragedy of war and the quagmire of Vietnam. The New World Order is no different. There is one scene in particular that has become common copy for our newspapers and news networks, and it is this: U.S. soldiers being greeted by hungry, destitute, or war-ravaged people with arms outstretched and eyes upturned in gratitude that their saviors have finally arrived.

This scene has been replayed many times this year, and each time the message is clear, the picture most telling, with only the geography and the troubled subjects varying the scene: the crying, spiritually broken Iraqi soldier crawling to the leg of his American captor, the jubilant Kuwaitis reaching up to touch the soldier-laden American tanks rolling into a liberated Kuwait City, hungry and homeless Kurds reaching to the heavens to catch the U.S. military assignments of food and supplies, the sick and battered Bangladeshis chanting “faresta! faresta!“—Bengali for “angel”—as the American military helicopters hover thunderously overhead. Frank Capra could have engineered no more moving and powerful pictures.

These are the scenes that Americans must learn to appreciate and enjoy if we are to secure our role in the New World Order. The United States could not play the commanding role in the new order without an endless supply of helpless people ready to accept our solicitude and ministrations. Our leaders are ever ready to clothe the naked, heal the sick, and bring freedom and peace to all people troubled and oppressed as long as the naked, sick, troubled, and oppressed reside outside the United States. The ethnic strife between the Serbs and Croatians or Palestinians and Jews receives more press time and more presidential attention than the current tension and open warfare between Hispanic-Americans and blacks, and cars burning in Seoul, Johannesburg, or Jerusalem seem always to trump cars burning in D.C.

Indeed, our leaders are so obsessed with the security, stability, and prosperity of every country and culture but their own that they are even willing to place the social and political interests of other nations above those of the United States. Anyone who disagrees with this policy is branded and portrayed as reckless, bigoted, dangerous, or insane. A case in point. Pat Buchanan (along with several Chronicles contributors) was recently attacked by a Canadian neoconservative in what the Washington Post describes as “the foam-flecked” American Spectator: “Who wouldn’t be ‘viscerally hostile,'” went the attack, “to a capital A, capital F, ‘America First’ policy”?

Kipling told the British to take up the White Man’s Burden, but it never really was a “burden” at all. In fact, feeding and schooling the natives was the best justification for the old world order otherwise known as colonialism, a euphemism for imperialism. Which leads us to where Mr. Krauthammer errs. He takes President Bush too literally and unnecessarily demands focus and specificity for the new order. The New World Order is not, never has been, and never will be about self-determination or sub-sovereignty or about the exercise and propagation of grand schemes or specific doctrines; it is instead—simply and boldly—about the exercise of will and the propagation of American hegemony. It is about power, not principle, and in particular about the power to play Julius Caesar abroad while playing Nero amidst a burning Rome at home.

But there is a private as well as a public side to the New World Order. In addition to the exercise of public power for the propagation of American influence and control, there exists a dimension to the New World Order that involves the exercise of private power for personal gain, as Bob Feldman’s expose on “The Kissinger Affair” in the New York publication Downtown alleged last March. According to Mr. Feldman, Mr. Kissinger’s “international consulting firm” called Kissinger Associates—which according to an April 26, 1986, article in the New York Times Magazine peddles influence and access to high government officials for between $150,000 and $420,000, fees which surely have risen in the five years since the article appeared—has (or has recently had) among its clients the Fluor Corporation, which received a substantial oil contract from Saudi Arabia shortly before Iraq’s August 2 invasion of Kuwait, and the Kuwaiti government-owned Kuwait Petroleum Corporation, whose oil drilling had been suspended because of the Iraqi invasion. The Kissinger consultant working with the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation in the 1980’s was reportedly President Bush’s National Security Adviser throughout the Persian Gulf War, General Brent Scowcroft, who is reported to have been on the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation’s payroll from at least 1984 to 1986. Mr. Feldman says that it was also during this time that General Scowcroft became a director of Santa Fe International, shortly after it was purchased by the Kuwait Petroleum Corporation in 1981. The question all this leads to was succinctly posed by Murray Rothbard in the May 1991 Rothbard-Rockwell Report: “Is it a coincidence that it was Scowcroft’s National Security Council presentation of August 3, 1990, which, according to the New York Times (February 21) ‘crystallized people’s thinking and galvanized support’ for a ‘strong response’ to the Iraq invasion of Kuwait?”

Suzanne McFarlane, Henry Kissinger’s executive assistant, told me in a phone conversation that Kissinger Associates has “never,” either before or after the August 2 invasion, had a Kuwaiti client. Where are all the Woodwards and Bernsteins when you really need them?

We do know, however, that Henry Kissinger serves on President Bush’s Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board, which gives him access to classified information, and that General Scowcroft has recently held stock in a number of defense-related companies. He sold these holdings shortly before the Persian Gulf War began, including shares in General Electric, which Scowcroft valued at some $1 million, and stock valued at $50,000 in DBA Systems Inc., a Florida-based military contractor of which Mr. Scowcroft was a director before he joined the Bush administration. Under the ethics law governmental officials with ties to military contractors are barred from participating in matters of national security. To circumvent any possible legal difficulties, President Bush—the “ethics President”—had granted Mr. Scowcroft a waiver that enabled him to participate in national security issues despite his military-related holdings. Representative Henry Gonzalez (D-Texas), chairman of the House Banking Committee, began to investigate this situation last June. He even wrote a letter to President Bush, saying that he was “deeply concerned” about Kissinger’s influence and “especially troubled” by Scowcroft’s involvement in policymaking that could possibly benefit him financially.

We also know that Kuwait’s biggest cheerleader was not President Bush or Congress, but rather America’s preeminent public-relations firm. Hill & Knowlton, which a group of wealthy Kuwaitis hired at the cost of $11 million for a few months’ work. It was H & K that created “Citizens for a Free Kuwait,” the organization that conducted show-and-tell presentations before the Human Rights and Foreign Affairs committees of the House of Representatives and that arranged for members of Amnesty International and Middle East Watch to give detailed testimonies before Congress as to alleged Iraqi atrocities—the most noted being the one President Bush himself proselytized, that Iraqi soldiers allowed 312 babies to die after removing them from their incubators in Kuwaiti hospitals, a story we now know to be an utter fabrication for propaganda purposes. H & K even pulled off the unprecedented feat of conducting both morning and afternoon shows before the Security Council of the United Nations. As Arthur Rowse asked in the May Progressive, “How could a public-relations firm, acting at a moment of acute international crisis, turn the world’s principal deliberative body into an all-day sounding board for one of its wealthy clients?” Perhaps the answer lies in the fact that the president and chief operating officer of H & K was Craig Fuller, who had served as chief of staff to Vice President Bush, and that the head of H & K’s U.S. division is Robert Gray, who had been inaugural co-chair for the first Reagan-Bush administration.

In 1917 Woodrow Wilson sent American boys off to die for the sake of democracy. By the 1920’s, however, it was clear to many Americans that the motives for our participation in World War I were more complicated. Ethnic antagonisms played a part, but so did the desire for profits. Americans did not blindly believe all the scare stories recounted in the muckraking Merchants of Death and later revived in the hearings conducted by Senator Gerald Nye, but they did know that Wilson’s argument for democracy was backed by individuals who did well out of the war.

We knew this once, and then forgot it. The political class of the United States knows how to make good use of the pernicious amnesia that is so characteristic of democracy. Perhaps it is time for another Nye Committee to shake its confidence.

Leave a Reply