While the most famous member of the Lindbergh clan is undoubtedly the aviator and World War II-era isolationist Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr., the qualities for which he won renown—his courage, his Scandinavian severity, his willingness to stand against the tide of popular opinion, his dislike of cities and the elites they spawned, and (most of all) his opposition to the scourge of war—were even more concentrated in the person of his father, Charles Augustus Lindbergh, or C.A., as he was known to his family and friends.

Charles Augustus Lindbergh was the son of Swedish homesteaders who hacked a farm out of the Minnesota wilderness. Both the perils and the virtues of that life are dramatized in the story of a run-in that C.A.’s mother, Louisa, had with some “Injuns,” among the earliest practitioners of “wilding.” Confronted by a group of drunken Sioux banging at the door and demanding food, and with her husband out in the fields, Louisa barricaded herself and her children in the house. The Injuns left, grabbing the ax off the woodpile on their way. Louisa lit out after them—but not before changing into her silk dress so that she might overwhelm the savage miscreants with her dignified appearance. She pursued them down the road quite a distance and upbraided them so thoroughly that the braves were shamed into returning the stolen ax.

And a good thing, too, for the ax had been designed especially for her husband, who had been injured in an accident and could do no work without it. The severity of his injury meant that young C.A. had to take up his responsibilities to the family as soon as he was able, and this meant putting fresh meat on the family table. The man who would take on the Money Trust and the warmongers, who would endure accusations of treason and, eventually, arrest for his outspoken views, spent his youth in solitary contemplation of nature, hunting and traipsing the trails of rural Stearns County. His biographer relates that “no one could remember when Charles could not handle a gun,” and young C.A. reveled in the freedom of the hunter. The nonconformism that was to mark his political career was formed in the lone splendor of those woods that swathed the banks of the Sauk River.

What educational opportunities there were in those days came largely as the result of his father’s efforts. The first schoolhouse in the area was in a granary donated by August Lindbergh, but his own son did not take kindly to being confined in a classroom, often escaping to the green solitude of the surrounding forests. The real core of C.A.’s education occurred at home: Both of his parents were avid readers, and the family table was the site of much lively intellectual discussion. At the age of 20, he enrolled at the Sauk Centre Academy and Business College, which had no classes, only individual instruction, a method well suited to a young man whose main occupation was still hunting and trapping.

Young Lindbergh’s first head-on collision with the world came when the Minnesota legislature passed a law prohibiting the killing of birds for shipment out of state. He had been making a good living shipping barrels of game to a Chicago restaurant. But he had saved most of his profits, and he used this to finance his study of law at the University of Michigan, which he entered in the fall of 1881.

He settled down with his first wife. Mary, in Morrison County, 50 miles from his birthplace, in the town of Little Falls. As a lawyer, C.A. was famous for his honesty; he refused to represent his first potential client because the man was guilty. Among his clients were several local banks and the Pine Tree Lumber Company, and he prospered. But at the tail end of the decade, tragedy overshadowed him: Mary died in 1898 of complications following surgery for a tumor. From this point on, his personal life was a cause of great unhappiness. In 1900, he met Evangeline Lodge Land, a temperamental young woman, moody and unpredictable. She was beautiful and a little mad, not at all a suitable mate for the serious intellectual C.A., an austere man not given to emotional displays. After several years of marriage, they lived apart. Turning to books and the world of ideas, C.A. began to develop the political preoccupations that would mark the third phase of his career: Republican insurgent member of Congress representing Minnesota’s sixth district.

Lindbergh was, from the beginning, an insurgent Republican, although his views were more in line with those of the Populist Party. In 1906, he ousted the incumbent Republican congressman in a hotly contested primary and went on to beat his Democratic opponent by fewer than 4,000 votes. As the candidate of agrarian revolt against the “special interests”—especially the railroads and big banks—Congressman Lindbergh was the avatar of the Midwestern Republican populism that later evolved into the “isolationist” right of the 50’s and 40’s. It was a movement on behalf of the farmers, small manufacturers, and small country banks that had been Lindbergh’s clients and foremost supporters. Caught between the battling giants of Eastern finance capital, the farmers and small businessmen of the agrarian Midwest—having withstood the vagaries of the weather and the depredations of inebriated Injuns—found themselves confronted by forces that threatened to defeat them.

The panic of 1907, the result of inflationary policies pursued by Treasury Secretary Leslie Shaw, threw many farms into foreclosure and forced small businesses into bankruptcy; it also stimulated a consortium of bankers, in alliance with the Morgan interests, to renew agitation for the creation of a central bank, a lender of last resort backed by the federal government that would attempt to stabilize an inherently unstable banking industry. This drive to centralize the banking system was part of a broader campaign to cartelize the economy, spearheaded by the New York banks in collusion with the railroads, financed and coordinated by J.P. Morgan & Co. Unable to achieve this cartelization in the free market—competition kept springing up, defying the merger-mania of the Morgan interests and keeping prices at a reasonable level—the plutocrats turned to the federal government, establishing the Interstate Commerce Commission.

The movement for a central bank was designed to benefit the big banks at the expense of the small “country bankers,” fill the coffers of the Eastern elites and impoverish Midwestern farmers, and build up the great cosmopolitan centers while depopulating the countryside. For years, the Morgan interests and their Wall Street allies, including the rising Rockefeller oil interests, had been agitating for a central bank. Adopting an incremental approach, they enlisted the aid of professional experts and learned commissions. The Aldrich-Vreeland Act, passed by Congress in 1908, increased the amount of “emergency money” that bankers could create out of thin air; in this way, the great Ponzi scheme of fractional reserve banking—in which bankers keep on hand considerably less than 100-percent reserves—was further developed. Another development was the establishment of a National Monetary Commission to “study” the problem of banking “reform” and recommend a course of action—one that was, of course, preordained. The Eastern bankers wanted to knock out the competition from the country banks and simultaneously seize the power to inflate (and deflate) the economy at will, making profits all the way up and all the way down.

In his first major speech to Congress, Lindbergh argued that “speculative parasites” caused the panic of 1907 and perceptively noted that fractional reserve banking is inherently unstable, since “even the guaranty of bank deposits will not prevent panics, but would only defer the day by postponing the hour of fear.” The “expert” hirelings of the aspiring cartelists—academics who had studied in Germany and absorbed the Bismarckian conception of the “organic” state, centralized and dominated by a government-business “partnership”—eagerly imported the principles of autocracy and state privilege. The monetary system, they argued, must be organized according to “scientific” principles.

Lindbergh saw through this mumbo-jumbo, arguing that “there is no fixed science about money or credit, except so far as we can evolve it out of experience.” The flow of money could not be regulated like the flow of water because “as human nature is not steady, neither is money and credit, for the value of both are more or less seated in the human brain.” Value is subjective, conditional, and constantly changing in unpredictable ways; Lindbergh’s insight is a concise exposition of the subjectivist theory of value, 30 years before the “Austrian” school of economics came to America.

Not that Lindbergh and his fellow progressive Republicans were giants of economic thought. Some of C.A.’s economic notions —such as the odd idea that the town of Great Falls had far too many businesses, and that this was somehow “inefficient”—reveal a breathtaking ignorance of economics and the market. The positive program of the Populists and their successors, the progressive Republicans—the income tax, government control of “public” utilities, nationalization of the railroads, and (worst of all) various inflationary schemes—ran counter to their instinctual opposition to centralism.

The significance and great strength of the Populist-Progressive movement lay not in its positive program but in its role as an opposition movement, and this was the great attraction of politicians such as Lindbergh and Sen. Robert “Fighting Bob” La Follette: their sharp and insightful analysis of the power elite. Lindbergh’s critique of the Aldrich Plan, delivered on the floor of Congress, registers their protest with acumen and verve:

Wall Street, backed by Morgan, Rockefeller, and others, would control the [Federal] Reserve Association, and those again, backed by all the deposits and disbursements of the United States, and also backed by the deposits of the national banks holding the private funds of the people . . . would be the most wonderful machinery that finite beings could invent to take control of the world.

This machinery, once set in motion, was inexorable, and its sinister purpose soon became apparent to Lindbergh. As war broke out in Europe and the Lusitania sank beneath the waves, the hope that the United States might stay out of the carnage went straight to oblivion: Lindbergh wrote in a letter to his daughter Eva that “we are going in as soon as the country can be sufficiently propagandized into the war mania.”

While progressives throughout the Midwest opposed the war instinctively, Lindbergh had a comprehensive and systematic analysis of the causes of the coming conflict. In 1915, he published two issues of a magazine, Real Needs, in which he indicted the “Money Trust” and the “subsidized” press for scheming to lure us into the European imbroglio. He pointed out that “the Wall Street end of the Federal Reserve System” was the financial pillar of the Allies: The resources of the U.S. Treasury and depositors’ funds were marshaled in the service of the British and French empires. As Murray N. Rothbard put it in Wall Street, Banks, and American Foreign Policy, World War 1 could not have been financed by “the relatively hard-money, gold standard system that existed before 1914. Fortuitously, an institution was established at the end of 1913 that made the loans and war finance possible; the Federal Reserve System.” The new machinery of power, once set in place, “enabled the banking system to inflate money and credit, finance loans to the Allies, and float massive deficits once the U.S. entered the war.”

As the war hysteria reached new heights and Wilson edged toward intervention, Lindbergh charged that “invisible organizers” had “buncoed” the American people on the war question. But they were not invisible to the congressman from Minnesota: “Amid all this confusion the lords of special privilege stand serene in their selfish glee, coining billions of profit from the rage of war. They coldly register every volley of artillery, every act of violent aggression, as a profit on their war stock and war contracts.” The “dollar plutocracy,” not the Kaiser, was “the greatest foe of humanity.”

In 1916, as it became clear that America soon would enter the war, Lindbergh announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate: He wanted a wider audience for his views. His opponent, Frank Kellogg, a former St. Paul lawyer and nationally famous “trust-buster” during the reign of Teddy Roosevelt, made military “preparedness” the main issue of the campaign. As the war fever hit new highs, Lindbergh was clearly on the defensive, }et unwavering in his insistence that although he favored “safe and sane preparedness against unfriendly nations if they attack us,” he opposed “turning our country into a military camp.”

But the militarization of America was already half-achieved, and Lindbergh’s voice was raised in vain: He came in last in a four-way race, and returned to Washington a lame-duck congressman. Still, he was not silenced. The plutocrats, he charged, were behind the militarization effort: America’s expanded army and navy would be used in “wars of conquest,” not self-defense. He introduced a resolution in the House calling for a negotiated settlement of the European war. But all hopes of such a peace vanished on January 31, 1917, when President Wilson severed diplomatic relations with Germany.

Despondent yet defiant, Lindbergh bitterly denounced the Wilsonians to his fellow Progressives. “There isn’t any such thing as a war for democracy,” he argued. But would not war result in more government action, asked a friend, and more progressive reform? Lindbergh’s telling reply was that “war-born things” are inherently flawed. Prefiguring the rise of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, he prophesied that war would have to mean that “dictators will spring up, perhaps even here.”

The infamous Zimmerman note, which raised the unlikely specter of a Teutonic Mexico, had the war party frothing at the mouth. The House voted, 403 to 14, to arm American merchant ships. Of the 14 dissenters, Lindbergh was the most caustic: Although plenty of Americans had been killed on belligerent ships and neutral ships prior to the current crisis, he pointed out that “no action toward starting war was taken till the submarine warfare stopped the munitions makers sending their goods across the ocean.”

He knew who his enemies were: J.P. Morgan & Co. was massively invested in financing the export of munitions and other war materials to the Allies. In a final dramatic gesture of defiance, Lindbergh’s last act in Congress was to introduce articles of impeachment against five members of the Federal Reserve Board, all Morgan men, charging them with “high crimes and misdemeanors” and “conspiracy to violate the Constitution and the laws of the land.”

The outbreak of repression and hysterical witch-hunting that followed the declaration of war turned America into a virtual police state. The Espionage and Sedition Acts criminalized antiwar speech and led to a wave of arrests: D.T. Blodgett of Iowa was sentenced to 20 years in jail for urging his neighbors not to reelect members of Congress who voted for conscription, while Kate Richards O’Hare of Missouri was given five years for complaining that “the women of the United States are nothing more or less than brood-sows, to raise children to get into the army and be turned into fertilizer.” Around 2,000 Americans were prosecuted for violating the Espionage Act: Almost half were convicted, of which 70 were given ten years and at least 30 condemned to prison for 20 years. The repression was particularly harsh in Lindbergh’s home state of Minnesota. Citing the Minnesota Espionage Act, local prosecutors jailed someone who casually remarked to a woman who was knitting: “No soldier ever sees these socks.”

It was the nadir of American liberty, a time when Beethoven’s music was banned in Pittsburgh and Goethe and Nietzsche were withdrawn from library stacks. The Committee on Public Instruction, a government agency, turned the intellectual elites into the priesthood of the war god: Writers, economists, historians, and academics of every sort were mobilized into an army of propagandists which “instructed” the American people in the myth of German war quilt. In Nevada, a local Council of Defense held a “people’s trial” and found the local nonconformist guilty of “lukewarmness toward the cause of the United States and their allies,” a “crime” for which he was duly tarred and feathered. In many states, including Minnesota, such groups had official status as the “Commission on Public Safety,” and they practically ran the state. The Minnesota antiwar agitator who declared that “we are going over to Europe to make the world safe for democracy, but I tell you we had better make America safe for democracy first” was arrested by order of the commission, and his conviction was upheld by the Supreme Court on the grounds that “every word he uttered in denunciation of the war was false,” and “it would be a travesty on the constitutional privilege [of free speech] to assign him its protection.” A small-town Minnesota newspaper editor was attacked and his presses destroyed because he was not sufficiently critical of the Non-Partisan League, a group of farmers whose muscular antiwar stance made them the target of jingoes throughout the Midwest.

Lindbergh had always been a party insurgent, loyal to his conscience rather than the leadership, and his final break with the GOP was telegraphed near the end of his congressional career, as he stood on the floor of the House in the summer of 1916 and declared: “The plain truth is that neither of these great parties, as at present led and manipulated by an invisible government, is fit to manage the destinies of a great people.”

Upon his return to Minnesota, he made common cause with a rapidly growing agrarian protest movement that had its main strength in the upper Midwest—and was just beginning to feel the first hammer blows of government repression. Founded in North Dakota in 1915, the Non-Partisan League was an association of some 200,000 farmers who were imbued with a radical distrust of the reigning elites and desperate to maintain their way of life against the rising tide of war and state-privileged industrialism. Lindbergh chose the NPL as his vehicle of protest. In a letter to Eva, C.A. brushed aside her concerns about his new relationship with the League and stood by his decision to throw his lot in with notorious radicals: “I am a radical because I oppose the few and stand for the masses.”

At a Minnesota NPL rally, Senator La Follette answered a heckler’s question about the Lusitania by making the trenchant point that Wilson’s own secretary of state had implored the President to stop Americans from setting foot on that doomed ship. The Minnesota Commission on Public Safety, created in April 1917 and armed with sweeping powers to stifle dissent, demanded La Follette’s expulsion from the Senate, and NPL President Arthur Townley was hauled before a secret tribunal and questioned about the League’s activities. The NPL was under constant surveillance by state officials.

It was under these circumstances that Lindbergh accepted the nomination of the Non-Partisan League for governor. Republican Gov. J.A. Burnquist declared that he would not campaign because war-time was no time for politics: hi Minnesota, he declared, there were only two parties, “loyalists and disloyalists.” In reality, of course, Burnquist waged a very active campaign, addressing meetings of “loyalists” sponsored by the Commission on Public Safety and printing campaign literature at taxpayers’ expense. I’he smear campaign launched by the Burnquist camp and supported by the local and national media was even more acrimonious and far more dangerous for C.A. than a similar one would be for his famous aviator son when he was a leader of the anti-interventionist America First Committee on the eve of World War II.

The concerted press attack on Lindbergh focused on his book, Why Is Your Country At War? The book named names, fingering such lords of high finance as Morgan and Kulin-Loeb, key members of the “inner circle” that had “adroitly maneuvered” the country into war. The New York Times disdained Lindbergh as “a sort of Gopher Bolshevik” and equated with treason his “animus” against the plutocrats in that paper’s hometown. During hearings before the Senate Military Affairs Committee, war-hawk Senators James A. Reed of Missouri and John W. Weeks of Massachusetts read portions of Lindbergh’s searing indictment of “the intrigues of speculators” who had “dragged us into the war,” hectoring the witness, NPL chief Townley, on whether he agreed. The hysteria climaxed in the government seizure of the book and the destruction of the plates by government agents in the spring of 1918.

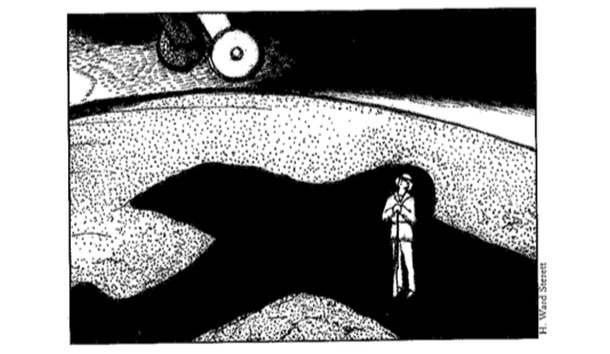

The demonization of Lindbergh in the press was the backdrop of a wide-ranging campaign of government repression directed at his gubernatorial campaign: The Public Safety gangs and anti-League judges banned NPL meetings in 19 counties. NPL organizers were arrested, and a reign of terror was unleashed on the membership. Subjected to a torrent of personal abuse on the campaign trail—run out of town, pelted with rotten eggs, hanged in effigy, and prevented from speaking in Duluth and towns throughout the state—Lindbergh did not relent. Addressing an audience of 10,000 farmers at Osakis, he declared that the war profiteers were “the real disloyalists,” for “even the pro-German in our midst is actuated by a mistaken sentiment for his fatherland, but these scoundrels, who stab our boys in the back, are moved by selfishness alone.” Campaigning with Rep. John Baer in Rock County, near the South Dakota and Iowa borders, Lindbergh and his campaign caravan were showered by a volley of shotgun blasts, aimed first into the air and then at the car. As the car pulled away, Baer scrambled to the floor, but Lindbergh sat up straight as an arrow and told the driver, “Don’t drive so fast. Gunny, they will think we are scared.”

Nine days before the election, Lindbergh was arrested in Martin County on a charge of “conspiracy” for conducting an election meeting. One hundred “volunteer guards” had been mobilized by state authorities, and they seized Lindbergh and hauled him into court. He was briefly detained, and the charges were quickly dropped, but the intent of the Burnquist forces to criminalize the opposition had all but succeeded. Burnquist’s victory at the polls—199,525 votes to Lindbergh’s 150,626—did not put an end to the controversy. The aftermath of the election proved nearly as stormy as the campaign.

Through the intervention of George Creel, a friend of the Progressives in the administration, Lindbergh was appointed to a seat on the War Industries Board. A national uproar ensued, and the chorus of outrage was echoed in a Minneapolis Tribune headline: “Capital Stunned Over Mysteru of Lindbergh Berth.” The intellectual vigilantes of war-time America made short work of Lindbergh’s naive belief that he could serve with honor in the war effort—just as they would scotch a similar attempt by his son to secure a military commission after Pearl Harbor.

Lindbergh’s political activities now revolved around the nascent Farmer-Labor Party, not only as a candidate but as a party officer and theoretician. He started a new journalistic venture, Lindbergh’s National Farmer, and came out with a book, The Economic Pinch, in which he developed the themes that had been the leitmotiv of his political career: the evil of the trusts, the privileged status of the banks, and the responsibility of the plutocracy for the war. Society could be divided into four classes: farmers, wage workers, entrepreneurs, and “profiteers.” The first three were useful and necessary to the workings of the national economy; the fourth was a parasite that lived by exploiting the others. In comparing our own plutocrats to the European aristocrats of the last century, Lindbergh warned that the Morgans could meet the same fate as the Bourbons.

A campaign for his old congressional seat went down to defeat, and yet another gubernatorial campaign ended when he suddenly fell ill and had to withdraw. Diagnosed with an inoperable brain tumor, he died on May 24, 1924.

C.A. Lindbergh understood who were the bad guys, and he was not afraid to name names. He saw through the illusion of American capitalism as a free, competitive system: He viewed it as a rigged game in which a few insiders load the dice and amend the rules at their pleasure. With a kind of X-ray vision, he homed in on the central scam of modern times, the Federal Reserve System, and recognized that the consolidation of central banking would mean the ultimate triumph of plutocracy over liberty and the defeat of the agrarian Midwest at the hands of Eastern cosmopolites. American freemen would become industrial slaves. He saw, too, that this private consortium of bankers, vested with the power to control the money supply, was a mighty financial machine perfectly designed to wage war.

Lindbergh knew what he was up against, but as he wrote to his daughter after his arrest as a seditionist, “this thing is bigger than anyone’s life, and I am not so cowardly as to be afraid for myself”

Leave a Reply