Ideology is an intellectual pathology that has gripped the West for about three centuries. At times, we have been told that ideology is at an end. This was said after the close of World War II, when the most ideological age yet, the Cold War, was just beginning. After its collapse, some 50 years later, we were again said to be entering an age without ideology. If anything, the disease has metastasized and is stronger than ever.

Ideologies come in wildly different forms: liberalism, Marxism, socialism, fascism, conservatism, neoconservatism, feminism; but as isms, they are all corruptions of reason. And because they mimic reason, the corruption lies hidden.

At bottom, the error of ideology is that it values one kind of knowledge too strongly over another. Knowledge can be divided into what Aristotle called practical wisdom and theoretical wisdom, or what we might call knowing how and knowing that. In the former, an action follows the how. I know how to raise a question in nuclear physics, how to speak French, etc. In the latter, a proposition or a theory follows the that. I know that bodies attract as the inverse square of the distance, and that it is immoral to treat persons as things. All human knowledge contains both kinds of knowledge, but they have different characteristics. In knowing that, we have a clear self-conscious apprehension of the object. In knowing how, nearly all the knowledge we enjoy is hidden from self-conscious apprehension. It exists as a potentiality, as something we know how to do even if we never do it.

Of the two kinds of knowledge, knowing how is primordial and is the more important. To see this, imagine an anthropologist who discovers a tribe in the Amazon basin that has never encountered modern people. By living with them, he learns their language and codifies its phonetics, syntax, semantics; its descriptive and performative uses; and its grammar. He then teaches the natives how to read and write their language. The natives now possess a large set of rules about their syntax, semantics, and grammar. But this knowledge, which has raised the self-consciousness of the tribal people, does not constitute the language, and it cannot guide the natives in speaking the language correctly. For they knew how to speak it correctly without any apprehension of the rules. Indeed, the anthropologist had to check his hypotheses about the rules against what the natives revealed to be correct usage.

The same is true of all the practices that make up a civilization. Science, morality, law, political conduct, architecture, medicine, theology, etc. are all practices in which knowing how is primordial (and largely unselfconscious) and knowing that is derivative and dependent. How do we gain this knowledge? Not by being taught propositions and applying them to experience, but by undergoing a long process of apprenticeship with master craftsmen in the practice. The process begins in childhood with parents, then moves on to apprenticeship with greater masters. In the end, one might become a master craftsman oneself—for instance, a physicist who knows how to raise a theoretically fruitful question in nuclear physics and can see immediately, without reflection, that a question raised by an amateur such as myself is silly, misplaced, or otherwise uninteresting.

Knowing that can be important in the mastery of a practice. Like a library system, it helps order knowledge into categories for convenience; distinguishes some aspects of a practice judged to be particularly important; and endows the practitioner with self-knowledge. These may aid in raising new questions and establishing new lines of research, but the aid is useless unless we know how to raise such questions and how to recognize the most fruitful path. Shakespeare could push the English language in new directions only because of a long period of apprenticeship and practice carried out largely pre-reflectively.

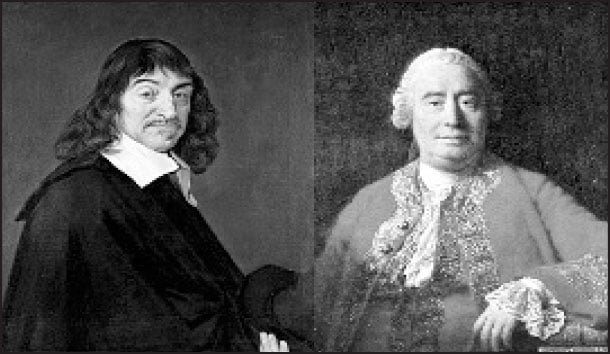

The error in the soul of ideology, then, is to think that knowing that is more important than knowing how—and, in the most extreme case, to deny that the latter is a form of knowledge at all. The extreme case is exemplified in Descartes, who is rightly said to be the father of modern philosophy. Descartes observed that, since tradition is not available to conscious apprehension, it is conceivable that the entire tradition is built on old wives’ tales and superstitions. To guarantee against this possibility, he argued, we must transcend the whole of tradition (that is, the whole of knowing how) to discover those universal principles that are absolutely certain and which alone can guide rational inquiry. Freed from the particularities of tradition, these principles would be the objects of knowing that.

Why would Descartes and his modern followers elevate knowing that over tradition to the point even of denying the legitimacy of tradition? One reason is that self-consciously apprehended principles give the thinker a sense of control. If, in addition, the principles are universal and certain, they seem to provide an infallible guide to a line of inquiry that will yield power. Descartes thought that, since he had discovered the absolutely correct beginning point for inquiry, the cure for death could be discovered in his lifetime. Bacon, following a similar path, famously held that knowledge is power. Because the knowledge locked in traditions is, for the most part, not available to self-conscious apprehension, it is not something we can control, and so it seems blind. Inquiry conducted in blindness, then, can only disorient thought. Another reason is that Descartes’ inversion was fetching to the new ethic of individualism that had been sweeping Europe since the Renaissance. To this newly created individual, who was determined to live life according to his own dictates, the thought that reason itself demanded emancipation from tradition was welcomed as something he had always known to be true.

Descartes realized that this degradation of tradition would be disastrous if applied to morals, politics, and religion. So he insisted that it be quarantined to the fields of natural science, mathematics, and metaphysics. But the opposite happened. Philosophers of science, not scientists, championed the ideologies of rationalism, empiricism, positivism, pragmatism, structuralism, and the like.

The Italian philosopher Giambattista Vico (1668-1744) was the first to perceive the devastating consequences from a style of education that would privilege knowing that over knowing how. He called the inversion “the barbarism of reflection” and countered the Cartesian revolution with a humanistic and tradition-laden conception of rationality. By the mid-18th century, a virulent ideological style of thought had entered politics and was beginning to move men and armies. David Hume observed that “no party, in the present age, can well support itself, without a philosophical or speculative system of principles annexed to its political or practical one.” Hume was the first to work out a systematic critique of ideology in politics—a critique that even today is unsurpassed. He showed that an ideology, far from being a rational source and guide for political conduct, is irrational, arbitrary, and no guide at all.

“Equal pay for equal work” seems to be a principle that is certain, universal, necessarily true, and capable of serving as a measuring rod for evaluating the justice of all wage settlements. Now consider this example: Two people are doing exactly the same work, stitching twenty pairs of shoes in an eight-hour day. One is paid ten dollars per hour and lives in Chicago; the other receives two dollars per hour and lives in Costa Rica. This settlement clearly violates the principle, although one might object that the principle cannot be applied across countries. Now suppose both live in the same country, but one worker belongs to a trade union and receives ten dollars per hour, while the other does not and receives eight. Again, it could be said that one must make allowance for trade unions. Now suppose that the same workers belong to the same trade union and live in the same country, but one factory is in Mississippi, the other in Chicago, and the latter’s wages are higher for the same work. Again, the principle is clearly violated, but one could plausibly reply that the cost of living in Chicago is higher. Or suppose the two workers in Mississippi are doing the same work for different employers but receiving unequal wages. A response could be that this would not be a violation because the wage settlements were freely entered into by the workers; we must allow for freedom of contract. Or suppose a male worker and a female worker are doing the same work for the same employer but at different wages. Should the state prosecute? No, not if the male is the head of a family. This was the teaching of the “family wage” policy, which favored married men over women in order to ensure that a male head of household would have an income sufficient to allow his wife to remain at home to rear their children. To demand the equality of wages would put men and women in a competition that would be to the disadvantage of stay-at-home mothers and, hence, to the family as the foundation of society.

In every case mentioned above, we cannot admit that the principle “equal pay for equal work” has been violated without ruling out a valuable social practice. So it is not the abstract universal principle that is critically guiding and correcting our practices; it is our practices that are critically guiding and correcting our interpretation of the principle. The principle, in itself, is indeterminate and cannot guide or correct anything. It must be interpreted to be “applied,” and the source of interpretation cannot be another abstract and indeterminate principle. Absent the authority of tradition, anything might appear to satisfy an abstract principle. It is for this reason that Hume called the new ideological critics “anti-Reformers”; knowing that cannot correct and reform society’s practices.

How, then, is rational criticism of society’s practices to proceed if not through an ideological critique? The way it has always proceeded when it has not been distracted by ideology: by loyal and skillful participants in the practices. Practices overlap and are in constant tension and conflict. The task of politics properly conceived is to understand these practices, their tensions and conflicts, and to render them as coherent as possible. An ideology such as egalitarianism is an abstraction of just one aspect of a society’s moral practices: equality. But there are other aspects that are valuable: liberty, consent, authority, circumstances, excellence, family, fraternity. All of these, considered as abstract ideals purged of custom and tradition, are incompatible with equality.

So one cannot think rationally about the justice of wage settlements without a connoisseur’s knowledge of the overlapping and conflicting social practices that constitutes society. In this correct form of critique, equality will be seen not as an absolute measuring rod but as one aspect that must be harmonized with conflicting aspects. Such criticism, however, presupposes a certain kind of education, one that forms people who naturally think that their conduct flows from inherited traditions and not from abstract ideals, and who have a connoisseur’s understanding of the historical details of their practices, without which rational criticism is impossible in any practice, including science. This is not the kind of education in morals and politics that has dominated modern society.

We are educated to think that a political ideology is both source and guide of political society. History, of course, will be taught, but only insofar as it conforms to the ideology. And, as we have seen, the standard for “conforming” is arbitrarily set by the ideology’s devotees. The rest of the tradition and its institutions will either be ignored or will be denounced as an impediment to the realization of the abstract principles. As the moral substance of tradition is slowly hollowed out by various forms of “critical theory” (what Vico called “reflective malice”), people gradually lose the knowledge of how to behave. And society becomes a battlefield of warring abstract principles: liberty versus equality; justice versus charity; authority versus consent; the right to life versus the right to choose. These conflicts must be settled by force or, as in the United States, by a regime of legalism. Those receiving an ideological kind of education and enjoying the benefits of tradition will feel guilty about their failure to “realize” the ideological principles; others will feel resentment. Persistent guilt, bad faith, and resentment are the public sentiments of an ideological style of politics and have their source in arbitrary power, not in sound moral judgment. And in such a regime, politics, viewed as the harmonization of the distinct interests embedded in an order of inherited practices, will gradually be pushed to the margin.

Hume was an astonished witness to this preposterous intrusion of ideology into politics. He distinguished between three kinds of political parties: those of affection (loyalty to ruling families), interest (loyalty to the practices and institutions that make a valuable way of life possible), and metaphysical principle. The first two have always existed and are legitimate, but the third is a pathology: “Parties from principle especially abstract speculative principle, are known only to modern times, and are, perhaps, the most extraordinary and unaccountable phenomenon, that has yet appeared in human affairs.” Hume contemptuously described his age as the first “philosophic age,” a time in which warring philosophical abstractions would dominate public speech and conduct. Legitimate parties of interest would continue to exist, but they would be stained, distracted, and distorted by an arbitrary and destructive ideological mode of politics.

This style of politics was resisted by Americans after it already held sway in Europe, but the temptation was here from the beginning. The watershed occurred when Abraham Lincoln presented the War Between the States not as a battle between concrete historic interests but as an ideological conflict between those who subscribe to certain abstract propositions about liberty and equality and those who do not. Before Lincoln began to employ such rhetoric, political parties openly pursued what Hume called “interests” (i.e., whole ways of life binding generations) and would debate whether the states or the federal government had authority to enact the preferred policy. Afterward, politics would be progressively trained to conceive of interests through the intoxicating and distracting fumes of an ideology. In time, only the abstract principles and slogans would remain, and people would eagerly embrace ideological political parties whose practices were positively against their culture and way of life.

Rather than recognize this style of politics as a moral catastrophe (Hume saw it as the most “extraordinary and unaccountable” happening in human affairs), Americans would celebrate it as a “progressive” achievement rooted in “American exceptionalism.” America is the first “proposition nation,” the first “universal nation,” the first “credal nation,” and because of her ideological credentials, she is uniquely endowed, as President George W. Bush has said, to lead a “global democratic revolution.”

Leave a Reply