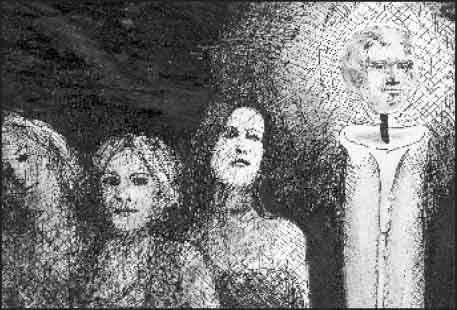

Are the Dixie Chicks traitors? Lead singer Natalie Maines boldly announced at a concert in London, just before the beginning of our recent armed incursion into Iraq, “Just so you know, we’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.” The firestorm that ensued involved coordinated radio boycotts of the Chicks’ music and Dixie Chicks CD-bashing events. Many of their fellow country artists disowned them, and, in a stunningly bizarre bid to win back their fans, the winsome Chicks posed nude, like three refugees from Paul Chabas’s September Morn, for the cover of Entertainment Weekly. They had provocative words, such as “free speech,” “Dixie sluts,” “Saddam’s Angels,” and—most importantly—“traitors,” scribbled all over their possibly airbrushed and improbably nubile bodies.

On March 17, 2003, the day President Bush issued his 48-hour ultimatum to Saddam, Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle, with possibly feigned solemnity, told a meeting of union leaders: “I am saddened, saddened that this president failed so miserably at diplomacy that we’re now forced to war. Saddened that we have to give up one life because this president couldn’t create the kind of diplomatic effort that was so critical for our country.” As reported by the Gannett News Service, a trio of Republican voices quickly rose to condemn Daschle. Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert said, “Those comments may not undermine the president as he leads us into war, and they may not give aid and comfort to our adversaries—but they come mighty close.” Senate Majority Leader Bill Frist labeled Daschle’s statements “irresponsible and counterproductive to the pursuit of freedom.” Finally, Tom DeLay, the second-ranking Republican in the House, blasted Daschle for “second-guessing our commander in chief on the eve of war.” Daschle responded that “To announce that there must be no criticism of the president, or that we are to stand by the president right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but morally treasonable to the American public.”

Similar criticism greeted other critics of the war in Iraq. For example, one contributor to the South Bend Tribune’s “Voice of the People” feature wrote in April that “these so-called ‘war protesters’ have no right to hide behind the First Amendment in expressing their sophistry,” and others labeled the protesters “so-called Americans” and “traitors,” who, as Tribune staff writer Andrew S. Hughes put it, “don’t measure up to their definition of what a ‘patriot’ is.”

Who is right about what amounts to “treason” and what a “patriot” should do? What is the obligation of a patriotic American when he believes that our government is increasingly engaged in actions that he cannot condone? Is there such a thing as honorable dissent that is a healthy part of patriotism?

Thomas Jefferson has recently been widely quoted, most notably by ACLU President Nadine Strossen, as maintaining that “Dissent is the highest form of patriotism.” However, distinguished University of Illinois historian Richard Jensen has noted on an historians’ listserve that it is unlikely that Jefferson made any such statement. While Strossen’s purported Jefferson quote, according to Professor Jensen, is probably “a recent hoax,” the real Jefferson, he observed, actually believed that dissent was dangerous. As Jefferson the president put it, excoriating those who objected to his ill-conceived embargo, “Where the law of majority ceases to be acknowledged, there government ends, the law of the strongest takes its place, and life and property are his who can take them.” In a similar vein, he observed that, “While the principles of our Constitution give just latitude to inquiry, every citizen faithful to it will . . . deem embodied expressions of discontent, and open outrages of law and patriotism, as dishonorable as they are injurious.” In 1797, Vice President Jefferson wrote that “Political dissension is doubtless a less[er] evil than the lethargy of despotism, but still it is a great evil, and it would be as worthy the efforts of the patriot as of the philosopher, to exclude its influence, if possible, from social life.” Strossen, then, gets Jefferson exactly backward.

Jefferson was often out of the mainstream of American politics and tradition, however, and thus we need to inquire further to determine what constitutes treason and what patriots ought to do. Consider the loosely leveled allegations that current critics of the administration are “traitors.” A traitor, strictly speaking, is one who commits treason, and treason is narrowly defined by the Constitution as “levying war against the United States,” or giving “Aid or Comfort” to her enemies. The Constitution also makes clear that treason consists of “overt acts,” and mere speech hardly qualifies—unless, for example, you use speech to pass on military secrets to nations or people hostile to us.

Treason is a capital crime, and, thus, it is no surprise that the law circumscribes it narrowly. When defenders of the Bush administration level this charge against their critics, though, undoubtedly they, following Jefferson, are simply trying to silence dissent, which raises the broader historical question: What have been the permissible limits of dissent according to the American tradition? To understand these permissible limits and the possible positive duties of dissent in America, we must, as the Framers insisted we should continually do, examine the “first principles” of our polity.

However, a distinct difficulty in engaging in such an examination is revealed each time we seek the “original understanding” of the Framers, whether it involves law, politics, or philosophy. Since the Framers were astute politicians, and since politics has always been the art of the possible, the framing of the U.S. Constitution was a series of compromises, leaving the resolution of many problems for future times and shrouding in uncertainty the exact nature of the compromises made. Thus, while the Framers generally agreed that state legislatures needed to be prevented from interfering with pre-existing contracts; that only the new federal government should be allowed to coin money, issue currency, and, in general, regulate interstate commerce; and while they were agreed that national defense and diplomacy needed to be centralized in the federal government, with most matters of law left to the states, the exact demarcation of federal and state powers and jurisdiction was left murky.

Perhaps the most striking area of disagreement, which became evident once the new federal government began to operate under the Constitution in 1789, was the purpose of the union itself. The group that began to coalesce around Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton (and which had been instrumental in advocating a strong role for the federal government in promoting interstate commerce) believed that America’s destiny was to be a great commercial power, one that would form strong alliances with other countries, particularly Great Britain. The Hamiltonians, believing that some kind of commercial aristocracy was inevitable, hoped to ally the interests of a rising commercial class with the betterment of all, and, in particular, to meld its interests with those of a strong central government. The group that began to form around then-Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson was much more fearful about forging ties, commercial or otherwise, with European nations. While Jeffersonian Republicans favored encouraging the popular revolution in France, they feared luxury as a corrupting influence and were determined that the mistakes in policy and government that had so long riven Europe would not be repeated here. In its purest form, their ideology advocated turning away from Europe, constraining as much as possible the power of the federal government to intrude on the lives of citizens, and dispersing land and wealth, so that individual citizens could better control their own destinies—much, if not all, of which was anathema to the Hamiltonian Federalists. Both groups, however, could find much within the original constitutional and political schemes to support their views, and a fair historian cannot conclude that either exclusively captured the original understanding.

Indeed, the tension between these two conflicting views, inherent in our laws, Constitution, and tradition, has provided much of the dynamic over the course of American history. As a people, we have been unwilling to let either view be completely dominant for long, and we have uneasily sought to preserve both. Hence the schizophrenic character of American politics and life, which still baffles foreigners. At some level, we seem to have understood that such a balancing act is necessary, and a right to dissent forms an essential foundation for maintaining such a balance. Thus the elevation of First Amendment freedoms of speech and press to supreme prominence in American life.

As Jefferson’s remarks indicate, however, this was not always the case. In the late 18th century, it was a belief common among our leaders that, as Supreme Court Associate Justice Samuel Chase once put it, there were only two ways to ruin a republic: the introduction of luxury or the licentiousness of the press. Indeed, some conservatives might justifiably still believe that the First Amendment is often the first refuge of scoundrels, and its invocation in cases involving child pornography, flag desecration, and compulsory public funding of the arts certainly contributes to that temptation. Still, it is also a part of American lore that we embrace the dictum usually wrongly ascribed to Voltaire that “I may disagree with what you have to say, but I shall defend, to the death, your right to say it.”

Our beliefs about a right to dissent were formed in the 18th century, as part of a struggle in England and in the colonies over the legal doctrine known as seditious libel. According to English common law (the body of practices not codified in statutes but administered in the English courts), no private citizen had the right to criticize the government. Any criticism of the government was thought to carry within it the seeds of sedition and, thus, was prohibited. The theory was that the king had been divinely appointed; to criticize the king’s government was indirectly to criticize God. In a nation with a state church and a monarchy and an aristocracy whose legitimacy was grounded in religious belief, dissent could not be tolerated.

More to the point, even those who did not seek to immunize the king from criticism on religious grounds believed that maintaining the delicate membrane of civil order required that criticism of the government be silenced, since the people, who rarely understood the complexities of affairs of state, were so easily misled by demagogues and malcontents. Thus the hoary doctrine of English common law that “The greater the truth, the greater the libel” held sway for centuries. True criticism of the government was deemed even more dangerous to civil order than false, because the truth was more likely to be believed, and disorder, sedition, or rebellion was likely to result.

This began to change in the century that followed the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution. In the famous case of John Peter Zenger in the 1730’s, some Americans (borrowing from radical English theorists) had begun to argue boldly that it was the obligation of colonists to criticize royal governors when they failed to accord citizens the established rights of Englishmen, chiefly those having to do with the protection of private property and person. Slowly, the common-law rules of seditious libel—and, in particular, the notion that “the greater the truth, the greater the libel”—began to change. By the end of the 18th century, in both England and America, the rule had been altered—first in practice, then by statute—to allow truth as a defense to a prosecution for seditious libel.

The truth of a statement was what lawyers call an affirmative defense, however, and that meant that anyone charged with seditious libel had the burden of proving their criticism of those in power was true, which was often a difficult task, particularly where matters of opinion were involved. This problem eventually led Thomas Jefferson and James Madison to argue that the doctrine of seditious libel, at least in the federal courts, was inconsistent with the freedoms of speech and press guaranteed by the First Amendment. Madison’s and Jefferson’s views, while out of the mainstream when they were first invoked, eventually became American orthodoxy, to the extent that no scholar would now seriously maintain that any criticism of the government—true or false—ought to result in criminal punishment.

While it may not have been the intention of the Framers, by the late 19th century, Americans seem to have adopted the free-speech theories of John Stuart Mill, expressed in his book On Liberty and endorsed by no less an authority than Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. In a famous 1919 case, Holmes wrote that “the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market.” The notions that there ought to be a “marketplace of ideas,” that truth ought to combat falsity in such a market, and that the truth might grow flabby if it is not constantly made to engage in combat with falsehood remain dominant in First Amendment law. With the exception of those (usually on the left) who try to impose speech codes at universities and others who seek to limit political debate by restricting the expenditure of funds to express a point of view (on the left and the right), our chattering class generally continues to endorse the notion that the remedy for speech or acts you deem inappropriate is more speech (though not necessarily more acts).

First Amendment theory, as administered by the courts, now even refuses to allow actions for damages to reputation of any public figures (politicians, actors, anchormen, and all others generally regarded as newsworthy) unless the person maliciously causing the damage (by speech or press) knows that what he is saying or publishing is false. The fact that any celebrity seeking such damages is now required to prove “malice” or “willful disregard for the truth” means that private libel actions for public figures are almost impossible to win. For some time, then, legally speaking, it has been open season on all public figures.

According to our tradition, then, it is wrong to label those who merely exercise their First Amendment rights as “traitors” or, perhaps, even to suggest that they are less patriotic than their fellows, Jefferson notwithstanding. This does not mean, of course, that other patriotic Americans cannot disagree with critics of the Bush administration (or any administration) or should not, when appropriate, subject them to ridicule. The South Bend Tribune’s May 4 issue quoted Woodrow Wilson’s suggestion that “[T]he greatest freedom of speech was the greatest safety, because if a man is a fool the best thing to do is to encourage him to advertise the fact by speaking” and noted that, as Vice President Hubert Humphrey once put it, “The right to be heard does not automatically include the right to be taken seriously.”

For the last two centuries, some Americans have, like Jefferson, occasionally sought to circumscribe permissible parameters of political debate. In the 1830’s, Alexis de Tocqueville noted that “In America the majority raises formidable barriers around the liberty of opinion; within these barriers an author may write what he pleases, but woe to him if he goes beyond them.” Tocqueville somehow failed to note the similar old saw that “You can always tell a Harvard man, but you can’t tell him much.” The current Commander in Chief, a Harvard Business School graduate, running against the stereotype, has wisely not personally impugned the patriotism of any of his critics. Those around him should follow his example.

€

Leave a Reply