William Pitt the Elder, in his Speech on the Excise Bill delivered before the House of Commons, encapsulated our Founding Fathers’ view of property rights when he said, “The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the force of the Crown. It may be frail; its roof may shake; the wind may blow through it; the storms may enter, the rain may enter—but the King of England cannot enter; all his forces dare not cross the threshold of the ruined tenement.”

Today, most Americans consider themselves residents of the freest country that has ever graced the earth, yet they are about as committed to property rights as they are to limited government, states’ rights, avoiding empire, and many other principles for which the Founding Fathers stood. I have been to city-council and planning-commission meetings. I have seen the way officials behave when a citizen asks for approval to remodel his home, build a new house, or start a new business. I have watched average Americans act like savages when their neighbors ask for a variance.

At a recent commission meeting, a developer proposed building 16 houses on roughly 30 acres of land that surround my dead-end street. Admittedly, I am not thrilled by the idea, since I enjoy the empty land adjacent to my home. I understand, however, that the land belongs to someone else, and that his proposed project is in keeping with my street’s original zoning. I attended the meeting, asked a few legitimate questions regarding the project’s tangible effects on my home (drainage, traffic, etc.), then spoke out in favor of the project. As I said at the meeting, before I bought my house, I went down to city hall, looked at tract maps, and inquired about the ownership of the land next to my house and about its zoning. I was told it was zoned for up to three houses per acre. I remember asking my wife, “Can you live with a few houses behind us? Eventually, someone will build there.” She said, “No problem.” That struck me as a reasonable way to do things.

My neighbors were not so reasonable, yelling and screaming and pounding their fists in the air. After all, they like looking at the land. One lady talked about how her kids like to play on it. And everyone agreed that, in this urban area, we need more open space for kids. I quietly mentioned that we should not be encouraging trespassing, but this did not resonate with my neighbors. (I am fairly certain that the same woman would not be thrilled if I showed up uninvited with some of my friends and threw a kegger by her backyard swimming pool.) I know most of my neighbors. They are polite and mostly conservative. Yet they behaved like a mob at the meeting. They are “stakeholders” who have a “right” to the current pastoral view. They believe the land should serve as a de facto park, and they would have been glad had the government simply banned any development on it without paying compensation.

At another meeting of the same planning commission, I listened as commissioners debated the appropriate hours in which a new business ought to operate. The commissioners had their own ideas about hours, signage, exterior look, interior design. The poor guy who stood before the council seemed amazed. To him, the whole affair seemed ridiculous: The commissioners spent about five minutes mulling over a situation in which he was risking a substantial amount of his own money. Yet, to obtain the necessary conditional-use permit, he had no choice but to agree to their conditions.

When I voice my objections to government-by-whim and to the obliteration of property rights, I routinely hear this reply: “Surely, you agree that government needs to set some standards on property use, zoning and otherwise. So, if you agree with some restrictions, then you shouldn’t complain about commissioners doing their job. You wouldn’t want a slaughterhouse next to your home, would you?” (Actually, a world without zoning restrictions would not necessarily mean slaughterhouses in the middle of subdivisions. Nuisance laws, protective covenants, and private-property associations could handle these matters quite nicely.)

Under our current zoning system, every property comes with a bundle of rights. When I bought my single-family home, I paid not just for the house itself and its postage-stamp lot, but for the entitlements that came with it. I have no right to demand that my property be rezoned to allow for the construction of multifamily condominiums. Likewise, the aforementioned developer bought the land adjacent to me at a price determined largely by the rules that govern that land—e.g., 3 homes per acre, not 4, 5, or 50. However, if the local government refuses to allow him to build any homes on his site, it has effectively stolen his land.

In other words, in a relatively free society, people have the right to do with their land what they choose, so long as they conform to some clearly defined standards that came with the property. As long as the developer plays by the rules, being careful to build according to existing zoning, the city should have little else to do but to inspect his plans and confirm that he has a construction bond. And, in a free society, there are relatively few rules to worry about, anyway.

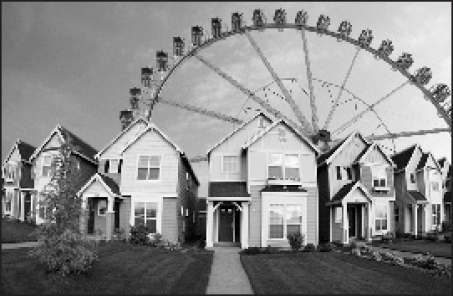

These days, though, there are lots of rules; yet, paradoxically, many local governments seem unbound by them. Review boards and commissions often give officials carte blanche to meddle in just about every property decision. Local governments insist that builders adopt certain designs and certain lot sizes. For a time, city officials demanded that most new homes be on larger lots, because they were committed to the creation of suburbia. Now, New Urbanism and Smart Growth are popular, so officials mandate high-density developments on tiny lots with most of the land set aside for open space.

Our city officials today are more like Soviet planners. Recently, the city of Brea, California, convinced a judge to deny the Walgreens drugstore chain permission to locate one of its stores in the downtown simply because officials preferred entertainment venues in that area. In the late 1990’s, the city had razed 50 acres of its old downtown and doled out $50 million in taxpayer subsidies to replace it with a gaudy new one that is more of an outdoor shopping mall than a real downtown. (It now boasts that the redeveloped “Birch Street” is a “village-style pedestrian-oriented promenade.”) Brea is also subsidizing hand-picked developers to build high-density housing in the area and using downzoning to deprive current owners of hillside land from building any houses on their property. Officials are careful to allow the current owners to build a handful of houses (as opposed to the thousand-plus they are legally entitled to build under current zoning) to keep the city from having to compensate them for the takings.

This sort of behavior leaves little room for enterprise or freedom. Property investments are uncertain: You never know whether officials will decide to reduce your land’s value with the stroke of a pen.

In my book Abuse of Power: How the Government Misuses Eminent Domain, I gave numerous examples of the increasingly common practice of cities driving homeowners and small-business owners off of their own land so that it can be transferred for pennies on the dollar to big national chain stores, who promise lucrative sales-tax revenues in return. This happens in almost every state. Often, the mere threat of eminent domain is enough to force people off their land. Cities claim that they need this power in order to get rid of crack houses and other genuine blight, but they have plenty of police powers at their disposal to deal with such issues. Instead, they use eminent domain mostly to assemble large parcels on behalf of wealthy developers. The stated goal is maximizing tax revenue, but the net result is that cities are deciding which neighborhoods get bulldozed and which companies benefit. It is no surprise that politically well-connected developers thrive and upstarts suffer.

Urban writer Jane Jacobs memorably said that “New ideas need old buildings.” Yet people with new ideas do not have a chance in the current environment. Cities have their general plans; their specific plans; their zoning, conditional-use permits, architectural standards, color palettes, historic-district designations, redevelopment areas, and layer upon layer of additional rules and commissions that must approve virtually anything that anyone proposes to build or do. All these rules rig the game in favor of those who are already wealthy, as they are typically the ones with the financial means, lawyers, entitlement consultants, and lobbyists who can gain all the needed approvals. Main Street businesses, small ethnic stores, longtime homeowners who just want to be left alone—they must give up their dreams for the greater good. Call this what you wish, but don’t call it a free society.

As with so many government-driven processes, the end result is often the opposite of what was intended. Cities impose so many rules and make it so difficult to build new houses that they drive up the cost of the limited supply and force people seeking affordable housing out into the hinterlands, where they are saddled with long commutes. The same officials who create these rules will turn around and lament the lack of affordable housing or the increase in congestion and sprawl. They then propose their government-funded solutions to these problems—inclusionary zoning, light-rail service. Previously, planners made it impossible for developers to build traditional towns and cities through their parking requirements and suburban-lot-size requirements. Now, those same planners are trying to impose a new set of rules to encourage urban living.

In her dissent to the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2005 decision Kelo v. New London, which allowed the city of New London, Connecticut, to use eminent domain against owners of historic homes in the city’s waterfront area, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor observed that

Any property may now be taken for the benefit of another private party, but the fallout from this decision will not be random. The beneficiaries are likely to be those citizens with disproportionate influence and power in the political process, including large corporations and development firms. As for the victims, the government now has license to transfer property from those with fewer resources to those with more.

That is an apt description of property rights in America today.

Big business rarely favors property rights. In California, when Proposition 90—which would have banned eminent-domain abuse and forced cities to pay for regulatory takings—was on the November 2006 ballot, the state’s business community did not sit idly by. They actively opposed it and joined forces with the California Redevelopment Association and other takings-happy government advocates. Yet these same business groups expect an editorial from me defending their property rights whenever the environmentalists or some other group seeks to limit the use of their land. I have a standard answer for them, but it is not fit to print in a family magazine.

Until more Americans are willing to stand up for the other guy’s rights, and not just for their own preferences, property rights will continue to fade away under a steady stream of rules, regulations, and government whims.

Leave a Reply