Most Americans in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries believed in the public expression of religious sentiments as surely as they believed in publicly proclaiming their patriotism. Such expression was not merely their right; it was their duty. Indeed, religious faith was part of the “given” of any political debate, the common ground upon which all candidates stood when they rose to disagree with one another. Even in the late 19th century—when great oratory had given way to high-blown platitudes—politicians could still, in all sincerity, invoke the Almighty at the slightest provocation.

Among the most common acknowledgments of religious faith were those delivered at ceremonial occasions where there were no votes on the table, no veterans or preachers to enlist, no pragmatic reason to haul out the colors of rhetoric. One such occasion was the inauguration of a president. At that moment, with the election over, the nation’s new chief executive and head of state speaks to the people for the first time. It was probably a much more significant occasion in earlier times than it is today, after so many televised debates, so many interviews, so many 60-second spots. But even in the 21st century, the significance of the moment remains.

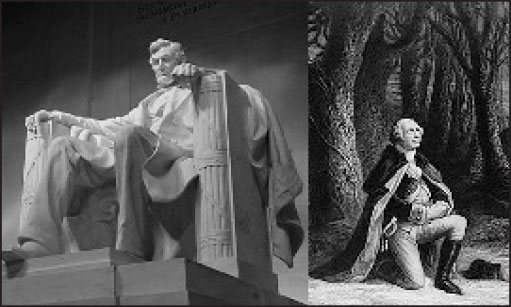

George Washington set the precedent in his First Inaugural by expressing his own submission to God and then the submission of the nation as a whole. He understood the special significance of this occasion. It was the first inauguration of an American president—first in what he expected to be an unbroken chain stretching into the future as far as the eye of imagination could see. He therefore had a special obligation to establish a precedent for succeeding presidents to recognize and follow. Note the wording and length of the following statement:

Such being the impressions under which I have, in obedience to the public summons, repaired to the present station, it would be peculiarly improper to omit in this first official act my fervent supplications to that Almighty Being who rules over the universe, who presides in the councils of nations, and whose providential aids can supply every human defect, that His benediction may consecrate to the liberties and happiness of the people of the United States a Government instituted by themselves for these essential purposes, and may enable every instrument employed in its administration to execute with success the functions allotted to his charge. In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own, nor those of my fellow-citizens at large less than either. No people can be bound to acknowledge and adore the Invisible Hand which conducts the affairs of men more than those of the United States. Every step by which they have advanced to the character of an independent nation seems to have been distinguished by some token of providential agency; and in the important revolution just accomplished in the system of their united government the tranquil deliberations and voluntary consent of so many distinct communities from which the event has resulted can not be compared with the means by which most governments have been established without some return of pious gratitude, along with an humble anticipation of the future blessings which the past seem to presage. These reflections, arising out of the present crisis, have forced themselves too strongly on my mind to be suppressed. You will join with me, I trust, in thinking that there are none under the influence of which the proceedings of a new and free government can more auspiciously commence.

This statement occupied a substantial and preemptive place in his text, preceding his discussion of more pragmatic matters of state. Indeed, the passage was longer than his entire Second Inaugural Address. Here, he said in so many words that, on such an occasion, propriety required the acknowledgment of God’s role in the destiny of the United States. For the first time, a president of the United States affirmed the belief that this nation had been especially blessed by God, Who looked with favor on its history and people. Succeeding presidents would echo these sentiments.

Washington, a faithful communicant of the Episcopal Church, specifically referred to the piety that all Americans shared at that moment when he said: “In tendering this homage to the Great Author of every public and private good, I assure myself that it expresses your sentiments not less than my own.” This is something about which we all agree, he was telling the new nation, but it needs to be said all the same at public occasions such as this one.

He even closed this paradigmatic inaugural address by again invoking God’s blessing.

Having thus imparted to you my sentiments as they have been awakened by the occasion which brings us together, I shall take my present leave; but not without resorting once more to the benign Parent of the Human Race in humble supplication that, since He has been pleased to favor the American people with opportunities for deliberating in perfect tranquillity, and dispositions for deciding with unparalleled unanimity on a form of government for the security of their union and the advancement of their happiness, so His divine blessing may be equally conspicuous in the enlarged views, the temperate consultations, and the wise measures on which the success of this Government must depend.

Succeeding presidents followed Washington’s example. Thus, Thomas Jefferson, poster boy of People for the American Way, paid homage to the God of the Holy Bible: “I shall need, too, the favor of that Being in whose hands we are, who led our forefathers, as Israel of old, from their native land, and planted them in a country flowing with all the necessaries and comforts of life.”

Following Washington’s example, every president, including George W. Bush, has mentioned God in his inaugural address (or addresses) to the nation, a fact highly significant, since, even in our own time—with the ACLU poised to pounce on every scurrying, squealing mention of the G-word—newly elected presidents have invariably chosen to reaffirm the nation’s belief that the United States remains a nation under God.

To be sure, many of these allusions to the Almighty were postponed until the final paragraph and, in their brevity, said little if anything about God’s specific role in the nation’s affairs. However, with one exception, they clearly appealed to a benign and gracious Creator and Preserver. In that one address, though, He is presented as the angry scourge of the nation, a God who rained death and destruction on the American people as punishment for sin. Such a God is described in the Second Inaugural Address of our 16th President.

At his first inauguration, Abraham Lincoln’s position as president was the very opposite of George Washington’s. Washington had won a war that had united his people and established a new nation. He was known to virtually every American and wildly popular, certainly the inevitable choice to be the nation’s first president. By contrast, Lincoln, relatively unknown and supported by a minority of the voters, was a polarizing figure, whose very election triggered secession. He was facing the prospect of a war that threatened to undo the nation Washington’s victories had established.

So how could Lincoln hope to avoid what William H. Seward in 1858 would call “the irrepressible conflict”? On what common ground could the two sides stand to engage in civil discourse? Lincoln knew that politicians North and South, as well as the people they served, were overwhelmingly Christian and that he was expected to appeal to the same God that Washington confidently invoked at the beginning of the nation. But Lincoln’s own belief—or unbelief—placed him outside the Christian community.

The best evidence shows that Lincoln did not believe Christ died to save the sins of the world or that He was the Son of God. On rare occasions, he accompanied Mrs. Lincoln to the Presbyterian Church; but, in an era where membership in a Christian denomination was de rigueur for politicians, he never joined. The people who knew him best said he was a freethinker, a scoffer, a man who looked on the New Testament as a crazy collection of stories and homilies that at best bewildered him.

Whether sincere or insincere, Lincoln, in his First Inaugural Address, said merely that “Intelligence, patriotism, Christianity, and a firm reliance on Him who has never yet forsaken this favored land are still competent to adjust in the best way all our present difficulty.”

Note that Lincoln first cited “intelligence,” then “patriotism,” both of which he addressed in the body of his speech. As for “Christianity,” he allowed the word to lie in its crib—unfed, unloved. It carried almost no rhetorical weight in this single sentence, which itself is no more than 30 words pasted near the end of a 3,633-word text. Like other presidents, he was following Washington’s prescription for an inaugural address, but he did not waste more than a single word on a religion for which he had little use, either as a practicing politician or as a man.

Lincoln spent most of the other 3,603 words appealing to “intelligence”—reasoning with those Southerners who had left the Union and those who were poised to do so. In these passages, he mustered his evidence like the good lawyer he was. First, he stated in clear, unambiguous language his position on the future of slavery, by quoting from one of his earlier speeches: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”

As for the so-called fugitive-slave controversy, he quoted the very passage in the Constitution that mandated return of escaped slaves, said the Constitution must be obeyed, and pointed out that “[a]ll members of Congress swear their support to the whole Constitution—to this provision as much as to any other.”

Having attempted to reassure Southerners that he was not to be confused with New England abolitionists, he told them in lawyerly language that the Union was a contract entered into by all parties and could not be rescinded unilaterally: “no State upon its own mere motion can lawfully get out of the Union; that resolves and ordinances to that effect are legally void, and that acts of violence within any State or States against the authority of the United States are insurrectionary or revolutionary, according to circumstances.”

In his two-paragraph peroration, he appealed, not to God or to the Southerners’ Christian beliefs, but to their “patriotism.”

I am loath to close. We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.

It is an eloquent conclusion to a well-reasoned argument obviously crafted to persuade Southerners rather than to inflame Northerners. One has to understand the highly complicated circumstances surrounding secession not to wonder why it did not motivate at least some Southern politicians to patch up the quarrel and remain in the Union.

Four years later—after hundreds of thousands of men had been killed on both sides (more Northern troops than Southern troops), Lincoln had won another election, and antiwar sentiment had boiled over in New York City and elsewhere. When Lincoln composed his Second Inaugural Address, he had seen his hope of a quick victory turn to ashes and his tenuous popularity turn to widespread animosity.

Unlike his perfunctory nod to Christianity and the “Him” in his First Inaugural, Lincoln relied heavily on biblical language in his Second Inaugural, quoting from the Bible, rhetorically clenching his teeth and pounding the pulpit like an Old Testament prophet, wagging a reproving finger at the sins of an entire nation, while specifically directing his fury (and God’s) at the people of the South.

He begins this sermonic address by reminding his audience of an ironic fact: Both sides in the war worshiped the same God, with each asking for help to prevail against the other. But he left no doubt as to which side had earned God’s wrath. The slaveholding South was unworthy to ask anything from God: “It may seem strange that any men should dare to ask a just God’s assistance in wringing their bread from the sweat of other men’s faces.”

Was he talking about Northern factory owners as well as Southern slaveholders? And about those who were living off dividends from industrial stocks? They, too, profited from the product of other people’s manual labor. However, as he developed his jeremiad, he made it clear: He was talking only about slavery. The ensuing paraphrase of words spoken by Jesus—“but let us judge not, that we be not judged” (Matthew 7:1)—was ironically, unintentionally self-mocking, since Lincoln had already passed severe judgment in the front part of the very same sentence.

Then—in a cleverly wrought passage that discussed God’s role in merely hypothetical terms—he suggested that the war, brought on by slavery, was the Divine Will intervening in history to punish the nation for the South’s sin.

The Almighty has His own purposes. “Woe unto the world because of offenses; for it must needs be that offenses come, but woe to that man by whom the offense cometh.” If we shall suppose that American slavery is one of those offenses which, in the providence of God, must needs come, but which, having continued through His appointed time, He now wills to remove, and that He gives to both North and South this terrible war as the woe due to those by whom the offense came, shall we discern therein any departure from those divine attributes which the believers in a living God always ascribe to Him? Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray, that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away.

This is a curious passage. In it, Lincoln spoke of the “Almighty” having “His own purposes.” Yet the quotation was taken from the words of Jesus, in a speech to His disciples (Matthew 18:7). Why not come right out and use the J-word? To be sure, orthodox Christians believed, then as now, that Jesus is God. But Lincoln did not. It is barely possible that he saw the quote somewhere and did not verify its source. However, it is highly likely that he used “Almighty” because it sounded more like the Old Testament God, Who was forever visiting disaster on those who disobeyed His commands, rather than Jesus, who tended to stress mercy and forgiveness. It was certainly a good quote for what Lincoln wished to say: that North and South alike had suffered because of the sin of slavery, but that the South (“by whom the offense cometh”) had incurred the greater punishment.

Yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said “the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.”

This address was delivered on March 4, 1865. In just over a month, Lee would surrender at Appomattox. The war was all but over, and Lincoln well knew the price Southerners had already paid for their attempt to leave the Union. Sherman and Sheridan—with Lincoln’s approval—had made war against civilians; burned their houses and crops; slaughtered their animals; and ordered troops to shoot men, women, and children at random. Yet in the Second Inaugural, Lincoln suggested that these war crimes were somehow ordained by the providence of God.

As the Gettysburg Address illustrates, Lincoln knew how to use biblical rhetoric to justify his own political choices and their catastrophic consequences. For a man who thought as little of Jesus as Lincoln did, in this address, he made mighty good use of the red-letter sections of the Bible—to curse his enemies and to picture himself as the instrument of God’s true and righteous judgment. In so doing, he stood Washington’s precedent on its head and once again revealed himself as the master manipulator of rhetoric.

Yet his ultimate affront to religious sensibilities occurred in his peroration, when—after using Scripture to scourge his enemies—he donned a cassock and became, in that white space between paragraphs, the benevolent dispenser of Christian grace, the peacemaker, the nurse of the nation that God had so sorely afflicted.

With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle and for his widow and his orphan, to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves and with all nations.

Small wonder he is regarded as our greatest president. You can fool most of the people all of the time.

Leave a Reply