My title is not the title the film is known by, but it is, with familiar strangeness, the title that we see, as the credits crawl “the wrong way” (in this film, the right way), imitating the unwinding of the road as seen from a speeding vehicle. In other words, the plane of the screen has become the plane of the highway, and the radio broadcast becomes the soundtrack of the film, as intoned by Nat “King” Cole. And the words and the music of that song, like the cinematographic aspect, have to be experienced to be apprehended in all their shocking fusion and confusion.

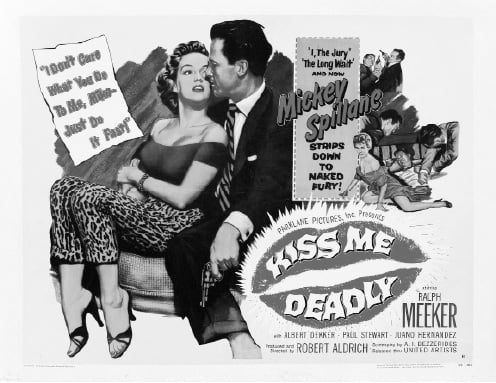

Kiss Me Deadly (produced and directed by Robert Aldrich, 1955) has enjoyed a cult reputation for over five decades, and as the years have gone by, our sense of the film has gone from strength to strength. It is quite possibly the greatest of all films noir, even one of the finest films ever made, of any kind. The bases of its appeal are many, and its aspects of repellence, not a few. But having been “done” as a Criterion DVD, it is literally an example of world cinema—a thriller as art film, a politically suggestive statement grounded in the repudiation of the detective myth. Kiss Me Deadly is, above all, an ironic and even grotesque rendition of contemporary awareness that has transcended its moment. It still speaks to us of a world of fear; of violence, mobility, and gadgets; and of secrets, cruelty, and abuse.

In the aspect of cinematography, the film scores many points with the harshness of its presentation, the unbalanced compositions, canted angles, and partial framings. The aspect of sound, both diegetic and nondiegetic, is equally remarkable: a babel of accents and tones, of clashing words and values, of contrapuntal episodes in which broadcasts of a horse race and a prizefight for the ear are juxtaposed with contrasted action for the eye—aural collage, as it were. And the mise en scène is the old Los Angeles before Bunker Hill was bulldozed and the Angel’s Flight was reconstructed. We must sense that Mike Hammer’s slick, sleek apartment is as repellent as Carmen Trivago’s sleazy one in this world of falsity, in which everything or even everyone is a trap, a distraction, or a threat.

A world of applied science (fast cars, radioactive material, and an automatic answering machine) is also a foregrounding of cultural references to the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament, to Greek and Roman mythology, to classical music and modern art. And just about all of that is over the head of the protagonist, Mike Hammer, though not of his nemesis, Dr. G.E. Soberin, who knows the lingo, if not the meaning, of traditional sanctions and warnings.

Such a complex presentation is populated with one of the most remarkable ensembles of character actors ever brought together. Not even John Ford or Preston Sturges could have excelled the gathering that includes Paul Stewart and Fortunio Bonanova (both from Citizen Kane), not to mention Percy Helton, Strother Martin, Jack Elam, Jack Lambert, Juano Hernandez, Wesley Addy, Nick Dennis, and so on. The three most prominent women of the cast I will address separately, as they are remarkable in their own ways, but Ralph Meeker as Mike Hammer, and Albert Dekker as Dr. Soberin, are distinctive and idiosyncratic performers, central to the film though not equally present on screen.

Kiss Me Deadly has a certain entertainment value, but it does not aim to please. It seeks rather to disturb and to disquiet the viewer as it follows an investigative line and episodic structure of frustration, leading to the revelation or discovery of an imponderable, dangerous something (the great “Whatsit”), an incendiary monster of radioactivity, the provoker of extravagant speculation and loose rhetoric ever since.

The reason for the oblique approach is that the film follows some of the plot of Mickey Spillane’s 1952 Kiss Me, Deadly (sic), a Mike Hammer pulp fiction. The film’s screenplay by A.I. Bezzerides is entangled with its own object of attack: At the end, Mike has to rescue his secretary, Velda, because that was the formulaic ending of the novel to be burlesqued or discredited. So the ending is no resolution—and the burlesque has shaded into the grotesque.

Not altogether coincidentally, at the moment of the film’s genesis, there was in the air a certain concentration of the imagination that defined film noir and its relation to the grotesque. After all, the very term film noir implies a relationship with the roman noir or gothic novel, and so we realize that even the hip or up-to-date aspects of Mike Hammer are brought into an orbit that Victor Hugo would well have understood. There is an affinity of noir with the horror film, for the roots are in early film and the appeal of the gothic mode. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari has become the box of the great Whatsit.

Raymond Borde and Étienne Chaumenton brought forth their Panorama du film noir américain (1941-1953) in 1955, wherein they ascribed to the distinctive type five qualities, as translated by Paul Hammond: “oneiric, strange, erotic, ambivalent, and cruel.” Kiss Me Deadly has all five qualities—and so do Hamlet, King Lear, and Macbeth. And I must point out as well that Robert Aldrich, the director, was photographed on the set of Attack! in 1956 with a copy of the Borde/Chaumenton book in his hand.

So before I assert that there is an antipattern in the exposition of Kiss Me Deadly, I must add that the opening scene, an outrageous complexity of sights, sounds, and sentiments, is at least one of the most striking beginnings in film history, and that the restored and correct ending that we see today is not only memorable and frightening, but also the cause of much overinterpretation. There is no question but that it is one of the most provocative endings ever beheld. Thus, Aldrich’s masterpiece has a powerful claim for the attention of anyone who does not know it.

For those who do know it, I have a particular suggestion of my own that, so far as I know, has not been voiced. My point is that there is a counterstatement within the movie of a narrative that has only fragmentary existence, yet is there. I want to point to the presence of Dr. Soberin throughout the film, not only at the end; to the presence of “the heavies” not once at the beginning, but three times in the film; and to the fraudulent presence of the pseudo-Lily Carver as an obvious ploy in her relationship with Mike. These three elements amount to a criminal conspiracy against Mike Hammer, and they are also an indictment of him as a detective, because he is a cognitive failure as a detective: He can’t detect, and for most of the film, he doesn’t know what he is after. This is in effect the meaning, not of atomic anxieties, but of the brute force of Spillane’s Mike Hammer: He’s too dumb to get the job done in a high-tech age. Much of the rest of the humanity presented in the film isn’t so brilliant either, as far as that goes.

The most impressive person on the other side is Dr. Soberin, though Mike never hears of him until most of the movie is gone. Yet the spectator feels he knows him. He is “the shoes” that are referred to as blue suede, though obviously they are leather wing tips. He is “the pinstriped trouser legs” known through parts only. And he is “the voice,” mellifluous and snobbish, the sound of what Mike is not. He says, “You are sitting on my coat,” as though Shakespeare had written it. He is the one who knows when Christina has been tortured to death and recommends that the unconscious Mike be put in the Jaguar with her corpse so that they will both be incinerated in the car crash he arranges with the assistance of the heavies, his goons. In a remarkable image, the black Cadillac of the gangsters is presented as a monster-face, with its grille as teeth, and lights as eyes, shoving the Jaguar XK120 to destruction. Later on, Mike’s Corvette (a booby-trapped gift from Dr. Soberin) will be similarly shown, and so will Mike’s reel-to-reel answering system. And also later on, Mike will be presented as “the shoes” himself, as he approaches William Mist’s apartment through his art gallery, terrorizing that worthy into swallowing a bottle of sleeping pills.

Now by “the heavies,” I mean simply the henchmen of the good doctor, but I also refer to the anonymous heavies of a thousand B-movies and a hundred serials. You know the look: They are so stout that they seem to be wearing bulletproof vests under their clunkily cut black suits. They usually are wearing dark fedoras, so they are generic, unrecognizable. They clumsily exert themselves in various ways, always uncredited and anonymous. They are bad. We get the picture. They are not important in the film, except insofar as they show the existence of another world, first with Dr. Soberin at the torture and death of Christina. Secondly, they are watching as Mike gets home from the hospital, so that his paranoia and fear is literally justified. And lastly, at the scene at the Pigalle, where Mike is passed-out drunk in a seizure of guilt over the murder of his friend Nick, it is a heavy who leaves the message that the bad guys have abducted Velda. This leads directly toward the end of the film. My point is that these types always know more than Mike does, and are organized and salaried. There’s not much mysterious about them except the ignorance of the protagonist.

The case of Christina’s roommate, Lily Carver, is something else again. For as we have already noted, Mike was known somehow from the highway, even when the police search could not find Christina. Mike was sent to die because Soberin assumed Mike knew something, though he did not. And then they knew where he lived, they knew his taste in cars, they knew where his office was, and they knew how he felt about Velda. They were always ahead of him. When he brazenly showed up at Carl Evello’s house, Evello recognized him—how? And discussed him over the phone with—Dr. Soberin, who else? But even so, the trump card in this game is “Lily Carver,” who points a gun at Mike, who is afraid, who let Christina’s bird die. Mike takes her at her word and says, “You want to get even for what happened to Christina, don’t you?” Sure she does! The next thing you know, Mike has to take her home to his pad because she is so afraid—all night they were trying to get in! So Mike put the fraudulent agent of the opposition—Gabrielle, Dr. Soberin’s mistress—into his retreat, where she can monitor him and report in. She is there when he finds the Whatsit in Raymondo’s locker, and disappears. The attendant is murdered, the mysterious box is stolen, and, at the end, the good doctor thanks Gabrielle for phoning him when she did. Mike betrayed himself for most of the film. So, there is some of the evidence that this grotesque burlesque of a detective story is an attack on its story, for the detective is dysfunctionally overmatched by a reality he can hardly comprehend.

In my focus on the protagonist, I have said little about the women of the narrative, yet I know very well how important they are. The most obviously striking one is Christina Bailey—the film debut of Cloris Leachman—who suffers and then dies, but not before she delivers a feminist diatribe that in the case of Mike Hammer is altogether warranted. There is nothing she says to Mike that he doesn’t need to know, and she even communicates to him from the land of the dead, as the character appears again as a corpse in a morgue. Even more important in her way is Velda Wickman (Maxine Cooper), another antimasculinist critic. This secretary is a virtual prostitute for Mike, but she loves him and she possibly redeems and saves him, as he weakly attempted to save her from the danger to which he had exposed her. The fraudulent Lily Carver, the mistress of Dr. Soberin, is really Gabrielle, as played by Gaby Rogers. No one who sees her will forget her simpering act or her incandescent demise. But not many know that this stage and television actress, who appeared in only one other film (also a noir), was a Jewish refugee from Germany, grandniece of the philosopher Edmund Husserl, and wife of one of the founders of rock music, Jerry Lieber. She introduced her husband to the works of Thomas Mann and helped with the lyrics of the song “Is That All There Is?”

Is that all there is? I should say not! Because the film is brimful of imagery, allusions, references, and ironies, it is a fountain of meanings. I haven’t undertaken here any comment on Mike’s Jaguar XK120 and its connection to the word jungle—to the suggestion that Mike Hammer is one predator among others. And this connects to the sign at the auto shop (where there are more Jaguar Mark Vs) that juxtaposes “Jaguar” with “Happy Holidays.” I haven’t undertaken any comment on the music that Mike hears but can’t respond to—the music of Schubert, Brahms, Strauss, and Chopin speaks of truth, beauty, and tragic awareness, but Mike, unlike Christina and even Velda, hears not, nor does he understand.

So finally, is that all there is? Not at all. I have only touched on the cinematographic experience, the grotesque, even hellish tour of the city, the alienation that oozes from every scene. But because Mike Hammer in Kiss Me Deadly is an antihero, a negative example, he has to be experienced to be known. Like Scarlett O’Hara, Charles Foster Kane, and Lawrence of Arabia, he spends a lot of time being wrong.

That’s why, somehow delighted by danger and disgust, we would be right to spend time with him.

Leave a Reply