Under our first president, the value of the Second Amendment was tested when George Washington faced the possibility of confronting armed citizens of the United States.

During Washington’s first term, a federal excise (commodities) tax became necessary just to run the federal government and fight Indian depredations. Congress placed the fully constitutional tax on distilled liquors throughout the United States.

It did not turn out to be an equal burden.

Farmers near the eastern seaboard sold their corn and grains profitably, for feeding people and livestock. But in frontier areas, such as Western Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina, the cost of transporting these crops to their seaboard markets would have destroyed the farmers’ livelihoods. So for years their crops had been lawfully converted to distilled liquors (“whiskey”) for ease and economy of wagon transport.

President Washington and his secretary of the treasury, Alexander Hamilton, were unaware that such a tax would crush the West. Furthermore, those farmers agreed with Samuel Johnson’s dictionary that an excise was a “hateful” tax. The British had imposed it on the colonies before the American Revolution.

Though the law was carefully amended and received almost universal approval, federal officers were boycotted, and armed resistance was threatened in the West. The farmers’ weapons, the famous Pennsylvania-German rifles later known as “Kentucky Rifles,” were better than military muskets. The rifles were grooved spirally for greater accuracy and range, and much lighter to carry.

In 1792, President Washington wrote to Hamilton,

If, after these regulations are in operation, opposition to the due exercise of the [tax] collection is still experienced, and peaceable procedure is no longer effectual, the public interests and my duty will make it necessary to enforce the laws respecting this matter; and however disagreeable this would be to me, it must nevertheless take place.

This would be the first test of the federal powers granted by the Constitution—and the right to keep and bear arms.

After three years of threats by the Westerners, Washington issued a proclamation warning those people engaged in resistance that the law would be enforced. He exhorted them to desist in harassing his officers. The President’s action was effective in the South, where opposition died out. But not so in Western Pennsylvania.

There, the Scotch-Irish borderers were bent on having their way. They were “a brave, self-willed, hot-headed, turbulent people,” in the words of Boston’s Henry Cabot Lodge, the President’s most famous biographer, and a supporter of a strong central government.

After the proclamation, the disturbances in the West increased for two more years, while “the mails were stopped and robbed, there were violence, blood-shed, rioting, attacks on U.S. Officials, and threats of worse.” President Washington finally concluded to a friend that “actual rebellion exists against the laws of the United States.”

By contrast, Hamilton’s enemy in Washington’s cabinet, Thomas Jefferson, in a 1794 private letter to James Madison, dismissed the “Whiskey Rebellion” as “anything more than riotous”—a matter for local police. “There was, indeed, a meeting to consult about a separation.” But to consult does not necessarily amount to separation or rebellion. He then went on to call the excise an “infernal” law, and declared that it had been wrong to permit it in the Constitution, as it also would be “to make it the instrument of dismembering the Union”—which the Westerners might attempt, if suppressed. However, Jefferson chose not to take a public position on the matter.

Jefferson had long established himself as highly suspicious of central power and all governments. Almost a decade earlier, when the states were under the looser Articles of Confederation, Jefferson had written to Edward Carrington about Shays’ Rebellion in Massachusetts that “ To punish these errors too severely would be to suppress the only safeguard of the public liberty.” And in a letter to James Madison, he noted that “A little rebellion now and then is a good thing . . . An observation of this truth should render honest republican governors so mild in their punishment of rebellions as not to discourage them too much.” In a letter to David Hartley, he reasoned that “[One] insurrection in one of thirteen States in the course of eleven years . . . amounts to one in any particular State, in one hundred and forty-three years . . . ” And to William Stephens Smith, he observed, “The tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants. It is its natural manure.”

Nevertheless, Jefferson later came to approve ratification of the new, stronger, Constitution. He especially approved of Madison’s Bill of Rights, with its Second Amendment, and the Tenth Amendment, which would reserve all powers not granted the federal government to the states and their people.

A delegate to the Constitutional Convention, Pennsylvanian Tench Coxe, had praised the proposed Second Amendment for allowing citizens to keep and bear arms against civil rulers and military forces that “might pervert their power” over the people. Coxe published this in his “Remarks on the First Part of the Amendments to the Federal Constitution” in the Federal Gazette in 1789, and received a thank-you letter from James Madison, who declared himself “indebted to the co-operation of your pen.” Madison went on to state that governments in Europe were afraid to trust the people with arms. The first American edition of Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England stated that Britain had outlawed private arms among people that they mistrusted, such as the Scots and Roman Catholics (until 1832). The Bill of Rights prohibited such actions.

An Englishman later praised his country’s unwritten constitution because a written one could simply be torn up, which prompted one wag to respond, “not if it is widely distributed to the people and backed with their firearms.”

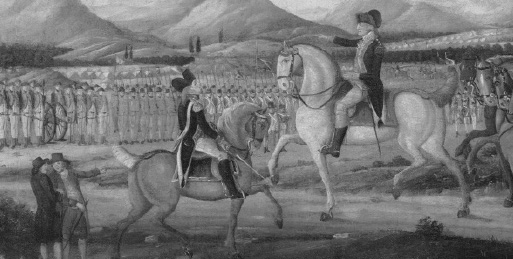

Eventually, President Washington called on the militias in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia to enforce the excise tax. The states all responded. Governor Lee of Virginia (Robert E. Lee’s father) was in command of 15,000 men, a large and overwhelming army at that time designed to serve as “a show of force.” It worked.

Lodge wrote of the outcome of the government’s approach, “The Scotch-Irish of the borders, with all their love of fighting, found too late that they were dealing with a [true] power.” The ringleaders were arrested and tried civilly, and the disorders ceased, permanently.

Washington used only state militias (armed private citizens), which had the right to refuse to serve, and there was no effort to disarm the “rebel” unorganized militias or any other Americans afterward. Indeed, the Western private militias were respected henceforth.

Today, the U.S. Code establishes “the Militia” in two categories: organized and unorganized. The latter consists of all able-bodied male citizens between the ages of 17 and 45; the former, the National Guard. Most state constitutions have almost identical provisions, though the current constitution of Texas also retains a third category, the active Texas State Militia, with the governor as its commander in chief, and it cannot be nationalized.

George Washington, America’s greatest and most revered president, felt it prudent and necessary to make sure of his rightness and public and constitutional support, and his probable success, before acting against well-armed insurgents, in part because of his knowledge that the protestors were armed with the same firearms he had—or even, in many cases, more lethal ones. Through his handling of the Whiskey Rebellion, the value of the Second Amendment was established without serious bloodletting. Anarchy was avoided, as was tyranny by the federal government, which the Second Amendment was designed to discourage.

If George Washington refused to violate the Second Amendment in his administration’s hour of greatest peril, how dare President Obama try to tinker with it now, when his administration has faced no armed opposition, and after his own civilian agencies just demanded more than a billion rounds of ammunition for fully automatic weapons.

Leave a Reply