Few decisions require more prudence and judiciousness than when a country’s leaders determine whether to go to war. They must weigh the cost in lives, national treasure, and security against the price of inaction. Morality may enter their calculations through the application of just-war theory. They will listen to, if not necessarily heed, diverse voices from the media, religious factions and ethnic constituencies, and assorted interest groups.

These interest groups often accuse one another of untoward behavior: Lack of patriotism is frequently the charge against those who resist America’s entry into war, while popular epithets for those who favor intervention have included “merchants of death,” “masters of war,” and “blood-thirsty warmongers.” While these debates normally begin with a reasonable amount of mutual respect and fair argumentation between the parties, history shows that, eventually, ad hominem attacks, demagoguery, and extralegal measures become the preferred weapons. The period leading up to our entry into World War II is a typical example of this pattern. Unfortunately, historians have recorded this period’s exchange of ideas using much of the same vituperative language and demagogic indictments as did the participants.

By late 1940, proponents of American entry into World War II were denouncing their anti-intervention interlocutors as, among other things, unpatriotic, fascist, right-wing, anti-American, pro-German, Anglophobic appeasers. Americans who thought twice about the wisdom of going to war were dismissed as “isolationists,” a word that elicited fears of a reemergence of nativism, xenophobia, and the anti-immigrant sentiments that had permeated the country in the first half of the 20th century. While not normally the best example of reasoned debate, political discourse in 1940-41 deteriorated into name-calling designed to vitiate the views of the anti-interventionists. Nonetheless, public-opinion polls consistently revealed that three fourths of Americans opposed entry into the European war. The America First Committee, the primary antiwar lobby, boasted 800,000 paying members, making it the largest antiwar organization in American history.

One prominent anti-interventionist was Garet Garrett, an editorial writer for the Saturday Evening Post from 1922 to 1942. Born in Pana, Illinois, in 1878 and armed with a third-grade education, Edward Peter Garrett eventually became an avatar of the Old Right with his critical musings on American involvement in World War II. For two years preceding our declaration of war against the Axis powers, Garrett inveighed against “the intellectual cult of interventionists.” In fact, some of Garrett’s fears, including worries of incipient imperialist ambitions, the destruction of the domestic economy through governmental interference, and a complete disregard for the Constitution and the rule of law, turned out to be prescient.

For years, historians have accused Charles Lindbergh of antisemitism for his Des Moines, Iowa, speech in which he identified “the British, the Jewish and the Roosevelt Administration” as the forces pushing our entry into the war. They have largely ignored the grassroots America First Committee, given disproportionate attention to the small and pathetic German-American Bund, and have pathologized almost all anti-interventionist dissent. Few of these same historians have tackled Garrett’s arguments, and even fewer have taken to smearing Garrett. The cogency of his arguments prevents such vilification.

As a proponent of laissez-faire economics, minimal taxation, and hard currency, Garrett fervently opposed Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. In a July 6, 1940, editorial, he mocked Roosevelt and his Cabinet as the “magicians who said there was an easy way out of depression” by following an economic program that he abhorred: inflation, confiscatory taxation, and wage and price fixing. Garrett saw all this governmental interference in the market as a truly ominous turn of events that would wreak havoc not just on the domestic economy but on the nation as a whole, as the transformation to a totalitarian state would be inevitable. He foresaw the military draft leading to the “total compulsion first of capital and then of labor.” If Washington could conscript young men, why should it not also conscript the capital of the wealthy? Roosevelt’s fireside chat of May 26, 1940, was further proof to Garrett that, since the government had tried unsuccessfully to enlist the business sector’s support for the war, the President was now trying the nefarious method of “suspicion implanted beforehand” in starting to nationalize the economy.

Garrett’s warnings in the economic realm have proved accurate. The payroll-withholding mechanism, designed by Milton Friedman and initially proposed as a temporary measure to fund our involvement in World War II, is still with us today, while the military-industrial complex, against which Eisenhower warned in his farewell address, is still going strong. Garrett was not a perfect prognosticator: His ultimate nightmare of a totalitarian state never occurred, as long as you exclude the TSA and certain elements of the PATRIOT Act.

Predictions of a global American empire fostered by the Roosevelt administration’s latent imperial ambitions also appeared in Garrett’s editorials. Before his appointment as an editorial writer, the Saturday Evening Post had taken a fairly unambiguous stance against all foreign interventions. America had been, in the opinion of the editorialists preceding Garrett, distinct from the other nations of the world for several reasons, including lack of the internecine conflict that had plagued Europe for centuries as well as the impenetrable geographic buffer of two oceans coupled with relatively friendly neighbors to the north and south. Despite the geographic expansion that followed the Spanish-American War and, later, President Wilson’s utopian desire to “make the world safe for democracy,” considerable anti-imperial sentiment still existed within the intelligentsia, especially at Middle American publications such as the Saturday Evening Post. However, even writers at the Post harbored no delusions that their admonitions against imperial expansion would get a fair hearing. By 1940, the Post editorialists declared that the “sense of separate destiny on which we had been building departed from us, and we have never since recovered it.”

Garrett refused to concede defeat. Sarcastically employing the language of his opponents, he saw entry into World War II as just the first in an unending chain of involvements to ensure global peace:

But before going to war in Europe, actually, the American spirit demands above all a crusading theme. Defense is not a crusade. The thought alone of crushing Hitler is not enough. What would come after that? There might be another Hitler.

Imperial overstretch had eventually destroyed all empires to date, and Garrett’s March 29, 1941, editorial, “Toward the Unknown,” perfectly encapsulated his concern that the United States was following the same path. He cites the break with our historical avoidance of entangling alliances (World War I notwithstanding), the discarding of the Monroe Doctrine, and the erosion of a unique American political culture and philosophy as evidence that we were starting a new imperial crusade:

We quarrel with the interventionists still, on the grounds that they conceal, or have not themselves the courage to face, what it means to this country, not merely to take over the war, but in doing that to assume a role in which it must either go on and on until it has gained moral hegemony of the whole world—or fail.

Garrett’s strongest arguments, and the bulk of his anti-intervention writings, focus on the constitutional impropriety of American involvement in a foreign war. By June 1940, Garrett was arguing that the United States had already entered the war when Roosevelt declared, with no help from Congress, that the Navy had a surplus of airplanes. The Navy would return these planes to the manufacturer, who could then sell them, with Roosevelt’s tacit approval and encouragement, to the Allies. In this way, the United States would obviate Article VI of the Hague Convention of 1907, which prohibited the sale of arms from any neutral power to a belligerent power, but which allowed such sales by individuals or private parties. Sounding as though the end of the republic was imminent, Garrett wrote, “So now be it said that in the one hundred and fifty years of its existence the house of constitutional republican government was betrayed, even as the builders feared.”

Garrett remarked that the United States had already gone a long way toward discarding the Constitution in favor of “unlimited democracy,” as evidenced by universal suffrage (which supplanted state laws in determining voter eligibility), the increasingly popular nature of presidential elections (in contravention of the constitutionally mandated Electoral College), and the direct election of senators. Garrett concluded his August 24, 1940, editorial (“This Was Foretold”) by stating that FDR “is the one whom the founders feared and partly foretold—I, Roosevelt.” In this same piece, Garrett gives a brief but thorough history of the Constitution and explains the Framers’ rationale for limiting the president’s power. Then, he fixates on Roosevelt’s “measures short of war,” which he viewed as sufficient to convict the President of abrogating the Constitution: supplying arms and munitions to the British through Lend-Lease; pledging support to the French; and entering into a military alliance with Canada, then a belligerent country. Roosevelt subsequently made a statement that would underscore his own duplicity: “Our national policy is not directed toward war. Its sole purpose is to keep war away from our country and people.”

America did enter the war in December 1941, and the editors of the Post punished Garrett for his dissent by arranging his departure on March 12, 1942. His actions after leaving were clearly those of an American patriot; even though he had argued vehemently against intervention, once we entered the war, his national pride shone brightly. In a letter to Donald Nelson, the chairman of the War Production Board, Garrett volunteered, “I am entirely at the disposal of the government, for anything it may wish me to do, for the duration of the war.” In a subsequent article in the Chicago Tribune (September 19, 1943), Garrett reiterated many of his themes, citing both Washington and Jefferson as support for his doctrine of nonintervention.

Garrett’s lone vocal defender today, Justin Raimondo of Antiwar.com, is doing yeoman’s work in keeping both Garrett’s message and works in the public domain. Raimondo’s sagacious reviews of Garrett’s books, as well as his ceaseless efforts to revive Garrett’s patriotic call, fall on deaf ears in a nation where our invasion of Iraq, though shown in countless ways to be unconstitutional, immoral, and a sheer waste of American life and limb, impels us full throttle down the path to imperial ruin. Garet Garrett, the anti-interventionist predecessor of the indefatigable Raimondo, provides many of the first principles for those patriotic Americans who refuse to condone or even accept the United States’ imperial overstretch. As in Garrett’s case, few of Raimondo’s critics have taken up the task of dissecting his anti-interventionist stance on the latest American incursion in the Middle East; it is easier to slander him and hope he eventually goes away.

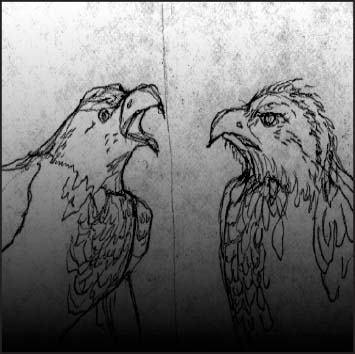

As to whether American foreign policy would be “that of the turtle or the bald eagle,” Garrett was unequivocal. Although he ostensibly contradicted his whole non-intervention thesis, Garrett proposed a patriotic definition of the terms appropriate to his philosophy: “The eagle is our symbol. A solitary people, devoted to peace, yet dangerous to any degree. Not an isolated people. A hemisphere people.”

As many students of history have concluded, it is easier to take on a turtle than an eagle.

Leave a Reply