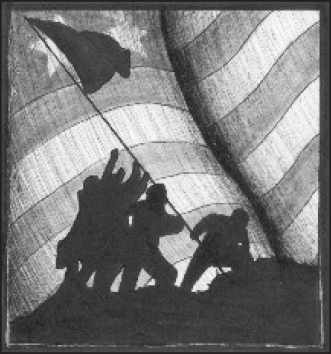

Flags of Our Fathers

Produced by Clint Eastwood, Robert Lorenz, and Steven Spielberg

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Screenplay by William Broyles, Jr., and Paul Haggis, from the book by James Bradley and Ron Powers

Distributed by DreamWorks Pictures and Warner Bros. Pictures

Because I thoroughly enjoyed the book, because Clint Eastwood is the director, and because Marines crave movies about Marines, I had high hopes for the movie Flags of Our Fathers. I was largely disappointed. The screenplay is terribly uneven; so, too, is the direction. Clint Eastwood is solely credited as director, but there are scenes so puerile and caricatured in nature that I would have sworn they had been directed by Steven Spielberg, the movie’s producer. William Broyles, Jr., and Paul Haggis are credited with writing the screenplay. This may explain much of the movie’s swings from good, to bad, to ugly. I would like to think that the good is the product of Broyles, a Texan, a Marine veteran, and a regular guy; and the bad and ugly, of Haggis, a Canadian who describes himself as a daring artist who breaks all the rules. I suspect Haggis takes himself a bit too seriously and forgets that his first duty is to tell a good story. Someone did break all the rules in Flags: The story swings from the present to flashbacks to the future to reminiscences to the present. About all that is left out is past perfect and subjunctive. Perhaps this is modern movie making, but it is not good storytelling. Every few minutes, we are reminded that we are watching a movie.

Having read the book, I thought that the movie would be about the battle for Iwo Jima and the six Marines—especially Navy corpsman Jack Bradley—who participated in the second flag raising on Mt. Suribachi, immortalized by Joe Rosenthal’s famous photograph. Much to my disappointment, Flags spends a wildly disproportionate amount of time on the War Bond Drive that the three surviving flag raisers were ordered to go on during the spring of 1945—and the greatest focus is on Ira Hayes, the American Indian Marine. I felt that I had been lured into the theater under false pretenses. Ira Hayes and the War Bond Drive would have been a more fitting title for the movie. Adam Beach, who plays Hayes, has the meatiest role, and he does an outstanding job. An Ojibwa Indian from Canada, Beach looks nothing like the real Ira Hayes, a Pima from Arizona. Beach is lean and nearly six-feet tall, a half-foot taller than the chunky Hayes. Beach could almost be a collar model.

More important than these physical discrepancies, though, are the suggestions in the movie that Hayes’ alcoholism was a consequence of the war. Actually, Hayes had been arrested for drunk and disorderly conduct on several occasions before he enlisted in the Marines. Then, too, the movie has Hayes talking a lot more than he ever did in real life—before, during, or after the Corps. Those who knew him growing up on the Pima reservation during the 1930’s consistently describe him as shy, withdrawn, and uncommunicative. He was like his father, who never spoke unless spoken to. Nonetheless, Hayes’ character in the movie generally reflects the real-life Hayes and is more fully developed than any other character, except possibly Bradley’s. The focus on Hayes is not long overdue—he was portrayed by Lee Marvin in The American (1960) and by Tony Curtis in The Outsider (1961). At least they got an Indian to portray him this time. Although not many know it, Hayes played himself in Sands of Iwo Jima (1949).

Also playing themselves in Sands of Iwo Jima were Jack Bradley and Rene Gagnon, the two other flag-raising survivors who pounded the War Bond trail. Ryan Phillippe does a good job working with what he is given portraying Doc Bradley. Nonetheless, the character is only thinly developed. To compensate for this, and for the underdevelopment of other characters as well, the movie has several History Channel moments with actors playing old vets recalling Bradley and others on Iwo. The interviews with the putative vets are some of the most awkward and jarring juxtapositions I have ever seen in a movie. Is this suddenly a documentary made for cable television? But not to worry. We are soon yanked out of the documentary and back to the movie. How many times are we supposed to suspend disbelief? All these devices ultimately make Bradley, a typical American boy caught up in a godawful battle, more an abstraction than a flesh-and-blood figure with whom we can empathize. Too bad, because the book has the reader feeling Bradley’s pride, strength, horror, and agony.

At the same time, the movie’s depiction of the grisly carnage and death that was Iwo is light years beyond what is done in Sands of Iwo Jima or any of the other good, old war movies. The old movies, far better in nearly every other way, are sadly lacking in blood and gore, which is a necessary reality check. As Robert E. Lee put it, “It is well that war is so terrible—lest we should grow too fond of it.” On Iwo, the Japanese rained artillery, mortar, and machine-gun fire down on the Marines landing on Green Beach from the heights of Suribachi. Hundreds of Marines were killed on D-Day, and hundreds more wounded. D+1 wasn’t much better. Most of the Marines killed did not have neat little bullet holes in them as John Wayne’s character, Sergeant Stry-ker, did in Sands but were blown apart by exploding shells. Torsos, limbs, and heads were scattered across the volcanic sands in a manner that made the beach look like a slaughterhouse. Doc Bradley’s role in treating wounded Marines is heart-rending and poignant—he saves some but loses many. He is scarred for life.

Stunningly, the movie makes nothing of the action for which Bradley was awarded the Navy Cross, second only to the Medal of Honor. Sprinting through 30 yards of withering Japanese fire, the brave corpsman threw himself between the flying lead and the body of a wounded Marine. With other Marines watching from foxholes, Bradley signaled them to stay put. He then stabilized the wounded Marine’s condition and carried him through the same wall of lead to safety. Those watching had no explanation for why he was not sliced to ribbons by the hundreds of machine-gun bullets that filled the air. Is not developing such a heroic scene this movie’s way of saying that everyone is equally a hero just for being there—or that there are no heroes? That is not the case in battle. Some men perform acts that leave others, with more practical attitudes about self-preservation, in awe.

Rene Gagnon is well played by Jesse Bradford, but Bradford is no Gagnon in what was most distinctive about Gagnon. The Marines of the 2nd Battalion, 28th Regiment, said, “We have our own Tyrone Power.” Gagnon was strikingly handsome and a dead ringer for the dashing movie star. Photographs of Gagnon are indistinguishable from those of Power. I suppose it is too much to expect a casting director to find another Tyrone Power, but Bradford, while a handsome actor, simply does not have the exceptional good looks necessary for the part. Coincidentally, the real Tyrone Power, a Marine pilot, made numerous landings on the island during the height of the battle, ferrying in supplies and hauling out wounded men in a C-46. Although he was one of the top stars in Hollywood and a civilian pilot, Power had enlisted in the Corps in 1942 as a private and went through boot camp at MCRD, San Diego, before going to officer’s school and flight training. Unfortunately, the movie misses a great opportunity to develop the multiple coincidences that connected Rene Gagnon and Tyrone Power.

The movie also misses a great opportunity to develop Mike Strank, Franklin Sousley, and Harlon Block as characters on screen. My wife, who had not read the book, had to ask me about the characters—the other three flag raisers in the photo. Sgt. Mike Strank was the squad leader and “a Marine’s Marine.” The son of an immigrant Pennsylvania coal miner, he was a physical specimen who inspired his men through example, leading from the front. He had been in the Corps since the late 1930’s and had fought on Bougainville before Iwo. Lanky Franklin Sousley was a red-haired and freckled-faced, smiling hillbilly from eastern Kentucky with, as a boyhood friend described, “the biggest hands I ever saw on a human—like two big hams hanging there.” Harlon Block was a powerfully built high-school football star from Texas. He and all the seniors on the football squad joined the Marines together. He is the Marine, back to the camera, planting the pipe flagpole into the top of Suribachi.

One movie cannot cover everything, of course, but Strank, Sousley, and Block loomed large in the book and seem to have been sacrificed for a focus on the War Bond Drive. Moreover, the movie is nearly two-and-a-half hours long, more than enough time for these essential characters to have been well developed. Take a look at what John Ford did with a war movie from an earlier era, Fort Apache. In two hours of screen time, more than a half-dozen characters are exquisitely developed. Clint Eastwood is purportedly a student of John Ford. I just cannot understand it.

Nor can I understand why Flags of Our Fathers does not properly introduce Iwo Jima: the nature of the conflict and the nature of the enemy in the Pacific; the reason for not leapfrogging the flyspeck of an island; the different type of defense the Japanese employed on Iwo; just what the Marines were expected to do. This could all have been done easily and quickly. A scene with intelligence officers briefing the men could have accomplished most of it. Moreover, I suspect most Marines will find it particularly irksome that the Marines are not particularly Marine. They could very well be soldiers. Yes, of course, we know they are Marines because history and the movie say so. However, the men do not act or speak like Marines. I asked a Marine buddy of mine, “How did you know they are Marines?” He was stumped other than to say that everybody knows that the Marines took Iwo. The Marines have their own particular argot—which, at times, can be almost a foreign language—and ways of issuing commands and answering those commands. NCOs and officers do things the Marine way, which is different from the Army way. This was all missing. So, too, was the special esprit de corps of the Corps, which is no romantic myth.

Also missing was the anger, the rage, that nearly everyone felt toward the “Japs,” the “Nips,” the “yellow bastards”—words never spoken in the movie. “Remember Pearl Harbor” and “Remember Bataan” were on everyone’s lips, in their thoughts. The Japanese bombed us in a dastardly sneak attack while we were at war with no one! Moreover, after the mind-boggling atrocities the Japanese committed on Guadalcanal, the Marines fought with a ferocity and a vengeance that was awesome. Intelligence officers begged that captured Japanese be brought in alive, but the Marines, by God, would have none of it.

Sgt. Ralph Walker Willis, who has written for Chronicles and who landed on D-day on Iwo and fought through to the end of the campaign, described to me how he and a buddy cleaned out one of the final pockets of Japanese resistance on Iwo. He, the buddy, and several other Marines, some with flamethrowers, worked their way down a rocky gully. On either side were caves and crevices that held Japanese. Flames were used to drive the Japanese from their lairs, and Willis and his buddy shot them down. Other Marines followed and emptied clips into the bodies of the Japanese, as if one killing were not enough. Finally, Ralph and his buddy reached a bluff overlooking the ocean at the other end of the island. The buddy sat down on the bluff, looked out into the ocean, and casually pegged a rock into the sea. Looking terribly forlorn, he turned to Willis and said dejectedly, “Shit, Ralph, we’re out of Japs.” For what the Japanese had done from Pearl Harbor forward, the Marines could not kill enough of them. The great Adm. Bull Halsey, just days before the atomic bombs, sent emergency requests throughout the Pacific for fuel and ammunition for his fleet. When asked what he intended to do, the Bull replied, “I want to hit the Japs one more time—before they quit.”

Perhaps a more egregious misrepresentation of history is the movie’s claim, spoken dramatically by a narrator, that, by the time of the invasion of Iwo Jima, the war had gone on for too long, people were demoralized, the nation was bankrupt. I cannot help but think that this is an allusion to the conflict in Iraq superimposed over the war in the Pacific. For the record, by the late winter and early spring of 1945, every American knew that Germany was on the verge of collapse and that we were one or two islands from Japan herself. American morale was sky high, the economy was booming, and rationing was ending. War bonds were still selling like hotcakes.

For those of you who have not read Flags of Our Fathers, do so immediately. You will want to keep it on your library shelf and read it again at a later date. For those of you who did not seen the movie, wait for the DVD and rent it. Problems aside, it is worth seeing once.

Leave a Reply