Appropriately, it was 1984. The Reagan-Bush ticket had won reelection. The U.S. Olympic team had destroyed everyone else at the Summer Games in Los Angeles. The HIV virus had been identified, and a cure for AIDS would surely follow. Hezbollah terrorists had bombed the U.S. embassy northeast of Beruit, and the CIA was busy training terrorists to carry out covert operations in Lebanon to stamp out terrorism. All was right with the world.

Except in Africa, where people were starving, while American yuppies sat at home in the lap of luxury. Fortunately, a collective of British pop stars decided to do something about it. Christmas was approaching, and American consumers were hitting the malls. Why not harness the horsepower of the American mallrat by letting him fill his stockings with cassette recordings of a new rock ‘n’ roll Christmas anthem and then send all of the profits to Africa to feed the hungry? Boy George, George Michael, Bono, and Simon le Bon—Christmas emissaries, one and all—joined hands, hearts, and voices under the name “Band-Aid” to produce “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” in which they chanted:

there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time

The greatest gift they’ll get this year is life

Where nothing ever grows

No rain or rivers flow

Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?

Seems kind of a shame, after all, for Americans to be sitting around at Midnight Masses or looking at manger scenes while heathens are starving in Africa—no yule log, no chestnuts. They do not even have snow.

Band-Aid, in all its glory, embodied the American Unitarian spirit of Christmas—a time to love, to laugh, to give. A time when, in the words of one Unitarian minister, “God does not put flesh on in the person of Jesus; God puts on my flesh. God is incarnate in my heart and acts in my life.” Sure, we believe in “incarnation,” but not the historic one in which God took on human flesh so that He might be born under the Law to redeem those born under the Law (heathen Africans and you and me). The Christmas myth teaches that each of us contains the spark of divinity, and that we—not as Christians or “little Christs,” but as little gods—are the Incarnation.

Much hay is made today among Christians regarding the commercialization of Christmas, but little is said about the Unitarianization of this, the “most wonderful time of the year”—maybe because most do not notice or mind. Yet the season of Christmas—especially Christmas Day, the Feast of the Nativity—is supposed to be a celebration of the central fact of the Christian faith. Take away the tinsel, the day-after-Thanksgiving sales, the Grinch, and folks dressed up like Eskimos, and what do you have left? Good, old-fashioned, American Unitarian Christmas, with “God bless us, every one,” and “every time a bell rings, an angel gets his wings,” and “angels bending near the earth to touch their harps of gold.”

Many, perhaps, do not realize that “It Came Upon a Midnight Clear” was penned by a Unitarian minister, Edmund Sears (1810-1876). This “Christmas carol” is sung in many Catholic, Lutheran, and Presbyterian churches, despite the fact that it does not even mention the “myth” of the birth of the Christ Child. Its message is frighteningly Unitarian:

But with the woes of sin and strife

The world has suffered long;

Beneath the angel-strain have rolled

Two thousand years of wrong;

And man, at war with man, hears not

The love-song which they bring; —

Oh hush the noise, ye men of strife,

And hear the angels sing!

The Christian era has been a mere “two thousand years of wrong?” What, then, is the purpose of Christmas? It is our opportunity to “hear the angels sing.” What do they sing? “Peace on the earth, goodwill to men from heav’n’s all-gracious King.” The final verse reflects the Unitarians’ intense post-millennial Utopian vision for America:

For lo! the days are hastening on

By prophet bards foretold.

When with the ever circling years

Comes round the age of gold;

When Peace shall over all the earth

Its ancient splendors fling,

And the whole world give back the song

Which now the angels sing.

If the deluge of worldwide bloodshed during the “Christian century” did not drown the manifest-destiny, Unitarian dreams of the unfolding “age of gold” in America, surely the World Trade Center bombing of September 11 did. Yet the gospel of American Unitarian Christianity and its Christmas remain the same. Figgy pudding in hand, Christmas is still a time of proclaiming saccharin peace and goodwill—not because of the birth of the Incarnate Son of God, who Himself “is our peace,” by virtue of the stripes He received at the hands of Roman soldiers. Just “peace and goodwill”—a mantra for postmodern, deracinated America.

It is odd that, of all people, Unitarians (such as the Reverend Sears) took to the robust celebration of “Christmas.” Unitarianism, after all, draws its very name from its denial of the Incarnation. Furthermore, the New England Puritans—that primordial soup from which Unitarians arise—loathed Christmas, calling it “diabolical.” In their minds, it was a shameful, “popish” innovation from which the Church must be purified. It was a crime to celebrate Christmas in Puritan Massachusetts until 1681. But the hyperrational, Socinian devolution of Puritanism that occurred in New England during the middle of the 18th century, which produced both evangelicalism (through the Great Awakening) and Unitarianism, also marks the beginning of the modem American incarnation of Christmas.

Today, American Christians lament the fact that, by and large, we have “taken Christ out of Christmas.” However, Christ has never really been part of Christmas in popular American culture, because the Incarnation has either been paid mere lip service (as is so often the case among evangelicals) or been completely rejected (as is the case with the “liberal churches” that later took the name “Unitarian”). This low regard for the Incarnation can, in fact, be traced back to the American Puritans.

That the Puritans had a low regard for the doctrine of the Incarnation may seem, on the surface, to be a scandalous charge. Indeed, when the “liberal churches” (as the Puritans dubbed them) began to declare openly that the idea that God became a Man was irrational, the few remaining churches in New England that held to the old ways broke fellowship with the liberals and refused to exchange pulpits with them. When the Puritans’ own Harvard College began teaching Arian Christology to its divinity students, the true Puritans left and formed a new school at Andover.

The Puritans who came to the shores of New England to form the Massachusetts Bay Colony in the 1630’s and 40’s believed that the work of the Reformation was left incomplete by Martin Luther, the Church of England, and even John Calvin, and they sought to purge the Church of the “leaven of Rome.” They also rejected the organic, incarnational understanding of the Church, declaring that neither apostolic succession nor the Sacraments (as genuine means of grace) are identifying marks of the Church but innovations added to the pure Christianity of apostolic times.

Unlike Catholics in Maryland, Lutherans in New York and Pennsylvania, and their own Anglican neighbors, the Puritans did not celebrate Christmas. Certainly, they did know how to celebrate: They were fond of commemorating everything (including the first Thanksgiving of their neighbors in the Plymouth Colony) with grand feasts and copious quantities of ale, brandy, and rum. But traditional Christian holidays were unacceptable, perverted, popish. Pure reason clearly perceives that the Bible never tells us to celebrate Christmas or any other Christian holiday—in fact (they pointed out), we are ordered not to respect times and seasons. (That St. Paul had Jewish festivals and Sabbaths in mind seems to have slipped past them.)

The Puritans thought they were restoring primitive Christianity. Instead, they were reviving old heresies while, at the same time, paying homage to pure human reason as the means by which man distills the truth of God both from the book of nature and biblical revelation. The New England divines were not the traditional curmudgeons they are now portrayed to be: They were young, innovative, and foolish, thinking that Christianity (unlike Christ) is not incarnational. In their brash austerity, they failed to learn the lesson of the central fact of Christianity: that God works through real, physical means.

Puritan sermons do include indirect references to the Incarnation, but little mention is made as to its importance in the grand scheme of salvation or its effect on the everyday life of the believer. What counts is an authentic conversion, followed by the living of a godly life. The Puritans eliminated the popish innovation of pericopal readings—the biblical lessons prescribed for each Sunday of the Church year. They also eliminated the Church year. In doing so, they removed the check and balance that kept the sermon focused on the events surrounding the life, death, and resurrection of the Incarnate Christ. Thus, they were free to preach abstractly, esoterically, and at length on Providence, the identifying marks of true believers, and “religious affections,” rather than, say, the significance of the Annunciation, the Nativity, or even the Cross of Christ.

While the Puritans spurned the writings of the medieval schoolmen, they were nonetheless obsessed with logic. As the monumental work of the late Perry Miller suggests, the Puritans traded what they perceived to be the syllogistic logic of Aristotle (and St. Thomas) for the aesthetic logic of Petrus Ramus. Ramus, a French humanist who converted to generic Protestantism in 1561, was a Platonist who believed that “science ought to study the lessons that are innate in select minds” and use them as a model to “formulate the rules for those who desire to reason well.” The incarnational philosophy of St. Thomas, whereby man builds his store of knowledge through real-world experience—founded on mankind’s historic encounter with the Incarnate Christ—is replaced by the inward-turning pursuit of innate ideas alongside the revealed truths of Scripture, under the alleged guidance of the Holy Ghost. For Aristotle, outward appearances were all we have to go by; for American Puritan divines such as Thomas Hooker, godly men are to judge truth based on the experience of “what is found and felt in the heart.” Hence, the Incarnation as a real-world event did not have a direct influence on the Puritan divines’ pursuit of truth.

Denying that regeneration is wrought by God through the Sacrament of Baptism, the Puritans insisted that God works directly on the mind and the heart, when man looks squarely on the biblical statements of “prophet bards” through the lens of human reason. Thus, they emphasized dramatic conversions, in which the light of God immediately penetrates the darkened mind of the sinner, and he is born from above, henceforth unable to do anything but follow God and obey His will.

Two strains of emphasis were commingled in Puritan thought (both were signs of the enlightened times): on the one hand, the direct, immediate divine working on the heart and mind of the individual to produce a radical conversion; on the other hand, the direct, immediate working of human reason on both nature and the Bible to produce or distill new theological truths. These two contradictory impulses parted company during the so-called Great Awakening of the mid-18th century.

Second-generation Puritan immigrants had failed to grasp the covenantal vision that had driven their parents to cross the Atlantic, and they had failed to catechize their children. Despite fiery jeremiads and annual Election Days, stalwart divines such as Increase Mather were incapable of motivating them to grasp hold of the ideology of the founders—John Cotton, Governor Winthrop—even though they were upheld before the people as icons almost on par with the Church Fathers. New England was prepared for nonconformist, itinerant preachers such as George Whitefield and John and Charles Wesley to sweep through the towns, preaching the “Gospel” of the conversion experience—without the cumbersome Ramist logic and covenant theology of the Puritans—to disaffected yeomen on the frontier along the Connecticut River Valley, as well as those less fortunate in the Eastern cities. Masses of unconverted, third-generation Puritans flocked to the fields (Whitefield was banned by many of the New England churches) to be born again or to rededicate themselves to God. Soon, great numbers of Yankee colonists had become “Christians” independent of any church and were setting out to find churches that catered to their need for exciting preaching and lively music. Evangelicalism—emphasizing the conversion experience and the moral life of believers—was born.

Upper-class professionals in eastern Massachusetts (especially Boston) and their rationalist Puritan ministers were shocked and dismayed at the news from the West that business was being neglected as folks dropped everything to partake of the “excitements” of the “new way.” In the words of the Rev. Charles Chauncy, some were

exhorting, some singing, some clapping their hands, some laughing, some crying, some shrieking and roaring out; and so invincibly set were they in these ways, especially when encouraged by any ministers (as was too often the case, that it was a vain thing to argue with them to show them the indecency of such behavior).

Such behavior was incongruous with the moral austerity of the urban East. Partly as a reaction to the “excitements” of “women, children, negroes, and ignorant men,” and partly because of the rationalism that had been transmitted to them from their forebears, the ground had been prepared for the freethinking, Socinian liberalism that was sweeping Scotland and England to take root in the established churches of urban New England. During the latter half of the 18th century, scholarly ministers began to apply the light of pure reason to the Incarnation itself, and the suprarational notion that God became Man in the Person of Jesus Christ seemed less and less tenable. The Gospel, they determined, means the transformation of the character of the individual by following the examples set forth in the Bible. American Unitarianism—emphasizing reason and the moral life of believers—was born.

Modern religious observers often note that evangelicalism is virtually the same as liberalism, just 50 years behind. That is because, by and large, they share many core principles, as well as a common origin in the Puritans. What distinguishes evangelicalism from Unitarianism is an intellectual commitment to what came to be known as the “fundamentals” in the early 20th century. Evangelicals retain a belief in the transcendent, supernatural characteristics of orthodox Christianity: the Virgin Birth of Christ, His substitutionary atonement for the sins of the world, His resurrection from the dead, and even His Incarnation in the womb of the Virgin Mary. ‘These core commitments cause evangelicals to follow the Puritans in emphasizing a dramatic, supernaturally enabled and inspired conversion experience. But for those already converted, the pursuit of individual piety is much the same as the liberals’—devoid of Sacraments and the “working out of salvation” that accompanies them. Since salvation comes through the instant conversion of the mind and heart, the Incarnation plays little part in the process of creating or maintaining faith and its goal, the forgiveness of sins. The Incarnation merely makes it possible, in the divine scheme of redemption, for the individual to receive Christ “in the heart,” whether that means the historic Jesus (as evangelicals hold) or the Jesus of myth (as the Unitarians hold). Personal (and social) moral betterment thus becomes the emphasis of Christian piety, since “salvation” is either something you have already got out of the way, or it is unnecessary. Thus, the meaning and use of Scripture, in sermons and Bible studies, is found in following the example of Jesus—or David, or Paul, or John the Baptist. Unitarians may not have invented the bracelet, but they have been asking “What would Jesus do?” since the dawn of the 19th century. A Yankee coalition of evangelicals and Unitarians answered that question by marching from one cause to another during the 19th and 20th centuries—from Abolitionism, to Prohibitionism, to suffrage, to the “war to end all wars.”

And it was on this basis that the Unitarians transformed Christmas into something that both liberals and evangelicals could enjoy—a clear departure from the Puritan past. By 1842, a new interpretation of the holiday was already in place:

I have always thought of Christmas time, when it has come round—apart from the veneration due to its sacred name and origin, if anything belonging to it can be apart from that—as a good time: a kind, forgiving, charitable, pleasant time: the only time I know of, in the long calendar of the year, when men and women seem by one consent to open their shut-up hearts freely, and to think of people below them as if they really were fellow-passengers to the grave, and not another race of creatures bound on other journeys. And therefore, uncle, though it has never put a scrap of gold or silver in my pocket, I believe that it has done me good, and will do me good; and I say, God bless it!

By the time that Charles Dickens, a Unitarian, put these words into the mouth of the nephew of Ebeneezer Scrooge, they rang true in the minds of his readers. It is “salvation by character”—one of James Freeman Clarke’s “Five Points of Unitarianism penned”—that both saves Scrooge and transforms Christmas.

Unitarians of Clarke’s ilk taught that man needs religion to inspire faith in “things unseen and eternal, to give him the hope of continued existence.” The new architects of Christmas borrowed images from Catholic, Lutheran, and Anglican traditions and stripped them of their incarnational value: candles, bells, even the Christmas tree. Though German Lutherans and Catholics had been decorating Christmas trees in New York and Pennsylvania since they first arrived in the colonies, it was Charles Follen, a German immigrant who became both a Unitarian and the first professor of German at Harvard, who actively popularized the Christmas tree in 1832 among Unitarians in New England. “It really looked beautiful,” one guest observed. “The room seemed in a blaze, and the ornaments were so well hung on that no accident happened, except that one doll’s petticoat caught fire.” Follen, an ardent abolitionist, liked the idea of the tree, because it inspired wonder, while its incarnational symbolism—the evergreen, representing eternal life; the lights pointing to the Light of the World; the tree itself, reminding us of the Tree on which the Christ Child would ultimately hang—is evident only to those who are taught.

Clement Moore, an Anglican convert to Unitarianism, penned the poem “A Visit From St. Nicholas” in 1822, transforming the memory of the charitable bishop from Asia Minor into the myth of an old man who works his elfen magic every Christmas Eve, bringing gifts to good boys and girls. Whatever his intentions, the effect has been long-lasting in America: What once was a real person who performed acts of charity as a response to the redemptive work of Christ (someone genuinely worth imitating) became an unreal, mythic figure, who inspires us to be nice to one another.

Unitarians quickly created a corpus of Christmas carols that replaced the rich, incarnational hymnody of Christmas past. They were uncomfortable with the bold lines of Charles Wesley: “Veiled in flesh, the Godhead see / Hail the Incarnate Deity” (“Hark! The Herald Angels Sing”). Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “I Heard the Bells on Christmas Day” echoed the sterile line “Peace on earth, goodwill to men” in the ears of his Unitarian brothers fighting amidst “the canons thund’ring in the South.” In 1857, John Pierpont, a Unitarian minister, wrote the delightful “Jingle Bells” as a Christmas carol, celebrating the joys of the one-horse open sleigh and laughter, minus the greatest motivation for joy and revelry. And the Reverend Sears painted Christmas using gnostic imagery of “angels bending near the earth to touch their harps of gold” and singing about “peace.”

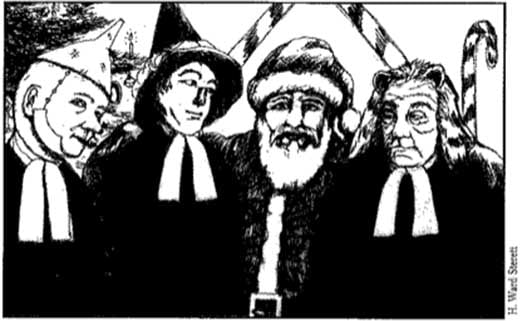

These Unitarian linages of Christmas cheer, transmitted to the 20th century by evangelicals and liberals—and Lutherans, Catholics, Presbyterians, and Anglicans under their influence (as well as the likes of Perry Como, Bing Crosby, and Bob Hope)—are at best sentimental, and at worst, anti-incarnational, which makes it interesting to ponder why the promoters of Kwanza, Hanukkah, and Ramadan are so put off by the remaining Christmas symbols in popular American culture. Others have reacted to the Unitarianization of Christmas in different ways. Some modern liberals invoke the spirit of “Band-Aid” and transform Christmas into a time to focus on solving world hunger, giving to charity, and working in soup kitchens. Some evangelicals emphasize the birth of Christ insofar as it provides an opportunity to evoke more conversion experiences. One local megachurch here in Rockford produced its own version of A Christmas Carol, in which Scrooge is taken on a journey into the past to see all of the opportunities he had to accept Christ as his personal savior. Some conservatives have returned to the rigorous hatred of Christmas that was once unique to the Puritans, only they call it “pagan” instead of “popish,” pointing out the origins of Saturnalia and the yule log.

More emphasis on generic “peace and goodwill” will, no doubt, flood the culture at Christmas during this, the real 1984, as images of the World Trade Center bombing are commingled with shots of bombs dropping on Kabul and star-studded galas with, perhaps, the Backstreet Boys singing “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” (Osama bin Laden makes a very nice Goldstein.) But a grave danger lies in absorbing Christmas symbols while ignoring that which is signified by them. Campaigns to “put Christ back into Christmas” are not only vain, they are destructive—if we leave out the Incarnation. When we celebrate the coming of Christ-the-mere-moral-example, we are (according to St. John’s First Epistle) celebrating the spirit of Antichrist. When we celebrate the Christ-who-enables-our-conversion-experience, ignoring the Incarnation, we also ignore the very means by which genuine Christian conversion occurs: through the infinite merits and suffering of the One who must needs be fully God and fully Man.

The antidote for the American Unitarian Christmas is not, as some suggest, to do away with Christmas altogether. America needs to rediscover the mystery of the Incarnation and incarnational, sacramental Christianity—a robust return to the collective wisdom of Christianity past. Unitarians and evangelicals (as well as the older traditions, which are so much under the sway of both) must look for inspiration beyond the American Puritan experience if they are to survive at all during these troubled times. There, they will also rediscover the true inspiration for Christmas and its crèches, trees, and bells. They will understand why we should kill the fatted calf and work in a soup kitchen. They will once again sing “Hodie Christus natus est” and “In dulci jubilo.” They might even sing “Jingle Bells” for the right reasons. And, facing the possibility of terrorist attacks, anthrax, or even World War III, they can, thanks to the incarnational hope offered by Christmas, “sleep in heavenly peace.”

Leave a Reply