In a rambling performance taking three-quarters of an hour, President Joe Biden spoke at Tulsa on the anniversary of the murderous events of 1921. He subjected his audience to his usual mangled sentences, omitting key words or parts of speech, sometimes to the point of total incomprehensibility. In fairness it should be noted that he is hardly worse in this respect than some of our other recent presidents; Bush II and Trump also had trouble constructing intelligible English sentences.

Yet despite the rambling, Biden’s speech offers some interesting insights into his thinking, or, perhaps, the contemporary cliches that he parrots.

In common with many recent commentators, Biden described what happened at Tulsa as a “race massacre.” This is accurate but abstracts it from the many other race (and other) riots particularly common in the era of 1917-1923, some of which can also be described as massacres, although none seem to have been as bad as Tulsa.

Like many others, Biden also described the Tulsa incident as among the worst massacres in our history, congratulating himself, and perhaps the rest of us, for finally discovering the event. “For much too long, the history of what took place was told in silence, cloaked in darkness. But just because history is silent, it doesn’t mean that it did not take place.”

After wallowing at length on the details of some of the disgusting murders, he then curiously rambled on about the destruction of property involved, as though that was practically as significant. After all the blather about “history” he linked Tulsa to the allegedly comparable violence against and oppression of other non-white groups. He took a break from the race obsession to note that the second Ku Klux Klan, founded in 1915, was hostile to others, notably his fellow Catholics, “who came to the United States after World War I.”

As so often happens, “history” has been turned into a prop for current obsessions. Hence Tulsa becomes a case of “domestic terrorism,” curiously bracketed with what happened a few years ago in Charlottesville—where just one person was killed!—and contemporary hate crimes against Asians and Jews, even though many of those have been committed by other minority groups, or mentally ill people who we have so humanely turned out into our streets. But all of this is the fault of white supremacists, who, Biden assured us, are the “most lethal threat” to America, not, Biden tells us, Islamic terrorists.

The relative casualty lists of 2001 and the deeds of white racist fanatics suggest otherwise.

Now, we can’t be sure just how many people were killed at Tulsa. We may have a better idea when the mass graves are exhumed, but it was certainly at least 40 and may have been as many as 300, although that last number is often misreported as an established fact in the media.

Uncertainty about the number of deaths, by the way, is also common in other riots and massacres of the era. It is a curious point, not often discussed, much less explained, that race riots and antilabor violence, sometimes incredibly bloody, were quite common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, although crime rates otherwise seem to have been rather low by later standards. Whatever remains to be found out about Tulsa, it almost certainly was not the biggest massacre in American history, as some suggest. That dubious honor belongs to the killings of at least 500 white civiliansin Minnesota by the Santee Sioux in the Dakota war of 1862.

Contrary to what Biden suggests, Tulsa was not a big secret—nor could it have been. The news media in 1921 was, by our standards, amazingly decentralized. It consisted of several hundred major newspapers; any decent-sized city in those days had several papers of differing political allegiances. The New York Times, on June 2, 1921, dedicated a page one headline story to Tulsa, estimating that 85 people had been killed at that point. An event given this treatment by the nation’s greatest newspaper was hardly a secret.

Nor was Tulsa forgotten by “history” any more than the second Ku Klux Klan. Practically any work about the period between the World Wars mentions the wave of race riots. The most famous book ever written about the era between the end of World War I and the beginning of the Great Depression, Frederick Lewis Allen’s Only Yesterday, a huge bestseller in the 1930s and often reprinted since, did not devote much space to race riots because that sort of thing was not Allen’s cup of tea. Yet despite this, Allen, after describing Chicago in 1919 as “virtually in a state of civil war,” mentioned Tulsa as a “another riot of major proportions.”

So much for “silence” and “cloaking in darkness!”

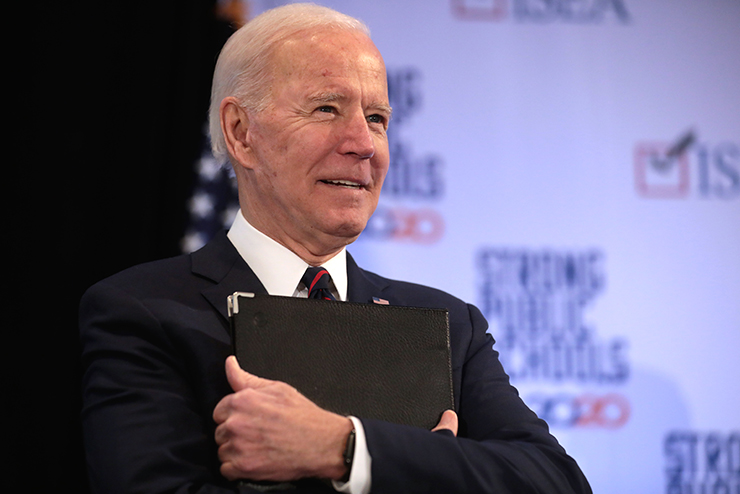

Image Credit:

Flickr-Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0

Leave a Reply