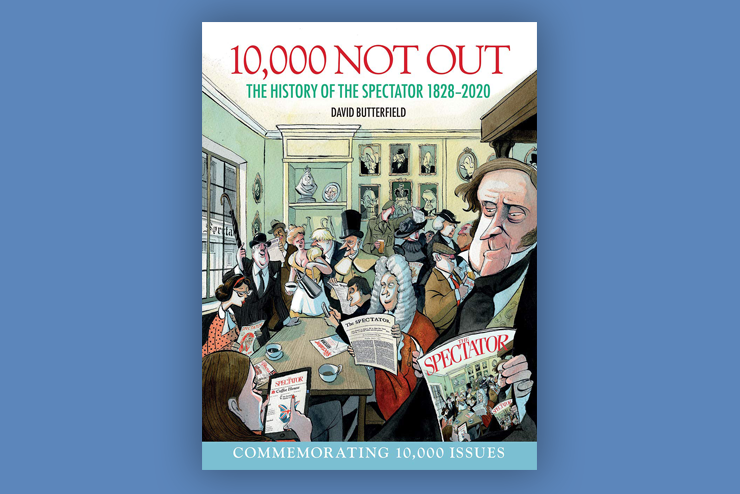

10,000 Not Out: The History of The Spectator 1828-2020, by David Butterfield (Unicorn; 224 pp., $30.00). Few journals have cut such a dash through history and culture as The Spectator, and none have lasted as long. David Butterfield has immersed himself to excellent effect in the British magazine’s billion-word digitized archives, paying tribute to a unique institution as influential now as at any time in its 10,000 issue history, and one miraculously still commercially viable.

His main aim is to show continuities of feeling and thought across all the incarnations of the magazine over 192 years and under 29 editors. The Spectator is sometimes dismissed as Tory press, but even when the journal has been edited by Conservative politicians, it has allowed contrarian views that have angered or embarrassed Conservative administrations. The Spectator’s co-editors between 1861 and 1897 said their object was to protect “the right of free thought, free speech, and free action, within the limits of law, under every form of government.”

Robert Rintoul started the magazine as a means to numerous liberal ends, naming it after Joseph Addison and Richard Steele’s eponymous earlier journal. It soon became a formidable champion of causes from abolitionism to electoral reform. Later editors were less obvious crusaders, but Rintoul would probably have approved of their generic dislike of “the Establishment” and the “nanny state,” which are common phrases that originated in Spectator articles.

Its best-known contemporary contributor is the irrepressible Taki Theodoracopulos (also of this parish), who has been delighting readers, appalling prudes, and causing awkwardness for editors since 1977 with his inimitable blend of high-society anecdotes, humorous insights, and outspokenness. It published right-wingers such as Enoch Powell, Roger Scruton, and Oswald Mosley, but also disparate personalities on the left, such as art critic Anthony Blunt, literature critic Terry Eagleton, and the double-agent spy Kim Philby.

But politics is only part of The Spectator, and maybe not even the most durable part. From the outset it gave generous space to the arts, carrying a glittering array of writers from Auden to Waugh, by way of Conrad, Eliot, Forster, Greene, Hardy, Lawrence, Nabokov, and Sartre—not to mention passionate arguments over apostrophes, etiquette, classical learning, clubmen’s gossip, nostalgia, bridge, and chess.

If sometimes narrow-minded and nepotistic, overall The Spectator has shown a rare openness to new ideas and talents. Butterfield’s book demonstrates that it has simultaneously helped make and mirror the British psyche, and to read it is not just to read the mind of the British right, but also the heart of a complex country.

Leave a Reply