Lately I’ve been hearing from colleagues and friends that Leo Strauss helped birth neoconservatism and that Straussianism and neoconservatism belong together rhetorically and conceptually. Supposedly neoconservatism would not have existed in the form in which it took over the conservative movement in the 1980s if Strauss had not provided its essential ideas. Thus, so goes the argument, neoconservatives and Straussians are so intertwined that it may be futile to distinguish between them.

This is an error which I fear my book, Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America, may have unintentionally nurtured. It’s time to set the record straight by restating my argument, which only partly overlaps the interpretation provided above.

It seems that Strauss, a Jewish refugee from Nazism, was driven by certain concerns that later resurfaced among neoconservatives. He was anxious about anti-Semitism, felt a deep attachment to the Jewish state of Israel, stressed Anglo-American friendship—which he associated with his hero Winston Churchill—and identified the American founding almost exclusively with Lockean natural right.

All these positions turn up among Strauss’s more prominent disciples and later in neoconservatism, which prominent East Coast Straussians like Walter Berns, Harvey Mansfield, Thomas Pangle, and Allan Bloom invested with intellectual respectability. Finally, many neoconservatives who went on to become policy advisors in the federal government, like Paul Wolfowitz, studied with Strauss or his students. The concerns and ideals of these foreign policy officials point back to Straussian sources.

Some overstate this linkage, however. Strauss was a respected figure among American conservatives even before neoconservatives discovered him. His Walgreen Lectures, which he delivered at the University of Chicago in 1949 and which were later incorporated into his book Natural Right and History, engaged key concerns of post-war conservatives about the twin threats of “relativism” and “historicism.” By the 1950s Strauss had become a reference point whom conservatives like Eliseo Vivas, John Hallowell, and Gerhart Niemeyer cited as a defender of moral values and a promoter of classical texts. Likewise, William F. Buckley, Jr. praised Strauss starting in the 1950s as a seminal conservative thinker; and Buckley’s former professor at Yale, Willmoore Kendall, was a correspondent of Strauss, who expressed deep respect for him as a critic of modernity. Furthermore, Strauss was admired for his scholarship by the Canadian Tory and High Church Anglican George Grant.

Although I differ with Strauss on his core assumptions—e.g., about the supposed evil of historicism, the value of Edmund Burke’s historical conservatism, on his almost exclusive focus on the natural rights founding of the American republic, and on the possibility of separating philosophy and political theory from theology—I would not deny that Strauss deeply influenced the American intellectual right even before the neoconservative ascent to power. His admirers took different ideas from his work at different times; and the neoconservatives celebrated Strauss differently from earlier enthusiasts.

Yet while the neoconservative appropriation of Strauss was the most conspicuous, it was not always the most faithful to the master’s views. For example, Irving Kristol repeatedly told his fans that, like Strauss, he preferred the political thought of Aristotle to that of Plato. Strauss’s actual position was exactly the opposite, which raises the question whether Kristol, the father of neoconservatism who claimed to be a Straussian, read his supposed teacher very deeply.

There have also been Straussians on different sides of the political fence. East Coast Straussians (who are really Chicago-based) have been politically well to the left of West Coast Straussians, whose citadels are Claremont and Hillsdale. When Cambridge University Press published my book on Strauss in 2012, this political split between the Western and Eastern camps was not yet obvious, but it has become unmistakable since then.

Today, East Coast Straussians are recognizably neoconservatives and in some cases Biden Democrats, while the West Coast followers of Harry Jaffa have joined the populist right. Although West Coast Straussians are theoretically closer to East Coast Straussians than they are to paleoconservatives, they are closer to the latter in their reaction to current events. I have also known students and followers of Strauss, like the late Stanley Rosen, who have no interest in the politics of their fellow-Straussians. Rosen was, however, methodologically a Straussian in how he read classical texts. The point to be made is that not all of Strauss’s disciples previewed what became neoconservative themes.

For those who think I have mellowed on this subject, let me stress that I stand by my earlier critical observations about Strauss’s work. But I wish to caution against the mistaken belief that Strauss first became part of the conservative conversation when neoconservatives took over the conservative movement. That longstanding connection dates back to the 1950s, as George Nash’s The Conservative Intellectual Movement Since 1945 abundantly documents. Further, Buckley turned decisively in the direction of Harry Jaffa and the West Coast Straussians by the early 1970s, an association that I clarify in my monograph, Conservatism in America: Making Sense of the American Right.

Southern conservatives and Straussians have long been at loggerheads on historical and political questions, and it’s doubtful they can be reconciled. But both have been forces in the conservative movement since the 1950s, although obviously not with equal power and resources. While Southern conservatives were expelled from the movement, starting in the 1980s East and West Coast Straussians prospered under neoconservative dominance. Still Southern conservatives and Straussians have both been in the conservative movement since its beginnings.

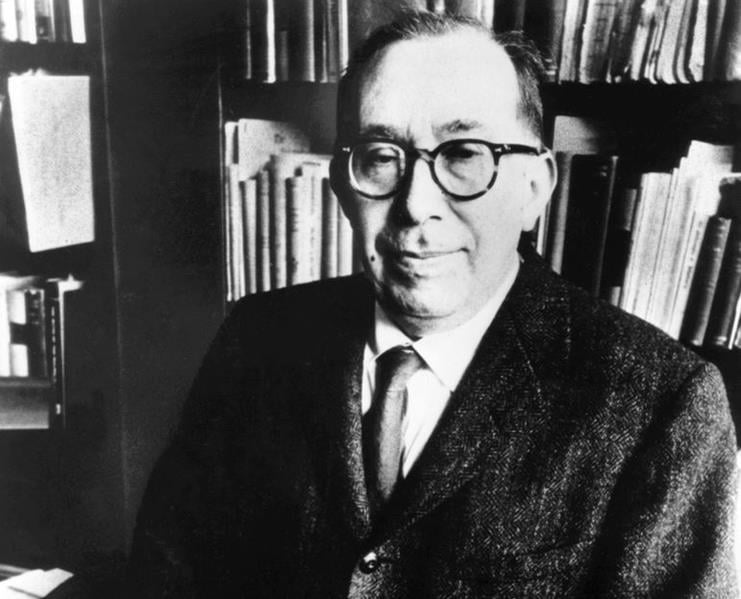

Image Credit:

Wikimedia Commons -University of Chicago, OR The New York Times , fair use

Leave a Reply