In the early 1900’s, Reconstruction studies (excluding the work of W.E.B. DuBois) approved quick restoration of states, Andrew Johnson’s strict constitutionalism, and white Southerners’ revolt against military and Republican rule (which consisted of carpetbaggers, scalawags, and freedmen). These studies—named the “Dunning School” for historian William A. Dunning, whose students applied his interpretation to individual Southern states—were “pro-Southern,” writes Eric Foner in Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution (1988), and portrayed black suffrage as the “gravest error” of the period. They are charged with glossing over what has been labeled “unreconstructed sordidness.”

By the 1950’s, historians did an about-face. The Revisionist school considered Johnson’s constitutionalism a veneer for racism and labeled the Ku Klux Klan terrorists, instead of freedom fighters. Revisionists also argued that Reconstruction was not a time of black supremacy and that Republicans were humanitarians, not vindictive opportunists.

By the 1970’s, a Post-Revisionist school considered Reconstruction a “tragic era” for reasons different from those of the Dunning School: Government intervention had been too limited, and the United States had abandoned the freedmen. Interestingly, many Post-Revisionists’ interpretations inadvertently support much of what the Dunning School found—for example, that U.S. soldiers mistreated the freedmen.

On today’s American campuses, Eric Foner’s interpretation of Reconstruction reigns supreme. Undergraduates not only learn about a Southern subregionalism and the freedmen’s experience but are indoctrinated with concepts of positive liberty and the supposed inseparability of race and class. Reconstruction was an effort, argues Foner, to live up to a noble creed. But then localism, laissez-faire principles, and racism “rearrested themselves,” and “the federal government progressively abandoned efforts to enforce civil rights in the South.” Reconstruction would have to wait a century before it was fully accomplished.

In the last two decades, Reconstruction historiography has emphasized black agency and fostered an awkward alliance among Dunning, Revisionist, and Post-Revisionist advocates. For example, a 2005 work asserts that blacks “transformed public education in the American South, to the great benefit of both black and white people.” Although such studies reflect a multicultural mind-set and frequently exaggerate black agency, they do reveal how black Southerners sometimes clashed with Northern missionaries and Freedman’s Bureau agents.

The historiography of education during Reconstruction has somewhat mirrored general interpretations of the period. Unfairly criticized and dismissed today for ignoring blacks, Henry L. Swint, in The Northern Teacher in the South (1941), argues that white Southerners did not oppose the education of freedmen but resented zealous missionary and Bureau teachers indoctrinating children. In the 1980’s, Jacqueline Jones’ Soldiers of Light and Love; Robert C. Morris’s Reading, ’Riting, and Reconstruction; and Ronald E. Butchart’s Northern Schools, Southern Blacks, and Reconstruction were the authoritative sources on Reconstruction education. They contended that paternalistic Northerners believed education solved all societal problems and formed an educational “army of civilization” to “Yankeeize” the South. However, according to Morris, blacks “needed land, protection, and a stake in society” more than they needed schooling, and Reconstruction’s “most durable myth” was the “stereotypical Yankee schoolmarm.”

Recent scholarship ignores the attitudes and experience of average white Southerners and considers Northern educators, at worst, as paternalists misguided by evangelical fervor. Rarely do modern studies investigate the mind of the white South during the turbulent days of Reconstruction, for historians are convinced that they already have it figured out. Influenced by postmodernism and multiculturalism, social historians examine only the gritty details of freedmen’s lives. And influenced by historical materialism, few wonder how ideas and worldviews affected Northerners’ and Southerners’ behavior or remember that ideological warfare raged across a war-devastated South.

One notable exception is historian John Chodes, whose Destroying the Republic: Jabez Curry and the Re-education of the Old South, uncovers what many modern historians have overlooked: an ideological war to redefine America.

As an Alabama politician before the War Between the States, Jabez Curry championed state sovereignty and limited government. After the war, however, Curry took the helm of the Peabody Education Fund. Chodes argues that this organization worked with authorities and public educators to eradicate secessionist thought and convince Americans to support a centralist regime. To Chodes, Reconstruction was a violent effort to redefine the United States, and the destruction wrought by this ideological war can still be seen today every time Americans unquestionably support government intervention.

In particular, Radical Republicans considered the War Between the States a “purifying act of God” and a means of retribution and collective salvation. According to Presbyterian Samuel T. Spear of Brooklyn, New York, in 1863, the United States must connect “the destinies of Christianity and civilization on this continent with one permanent, indivisible, powerful, progressive nationality,” because the nation was “made for growth, for increase of population, for the organization and addition of new States, for an indefinite augmentation of the States that glitter on its flag.” Southern secession, believed Charles Sumner, would divide and weaken the country, thereby preventing the establishment of a “national example” more “puissant than army or navy for the conquest of the world.” So, national strength had to be exercised, and secession made forever odious. Aaron F. Stevens of New Hampshire exclaimed, “The irresistible power of the nation . . . under Abraham Lincoln, was its strength, its glory, and its salvation, for no government can be respectable or respected unless it possesses and exercises sufficient power to crush out and place under its foot its enemies.” Stevens found allies among many Southern Unionists, who were, at times, every bit as nationalistic. A rag of vitriolic Methodist minister and Tennessee governor William G. Brownlow, the Knoxville Whig, read thus on March 28, 1866: “The endless perpetuation of the Federal Union is the gist of radicalism. Everything must be subordinate to that.”

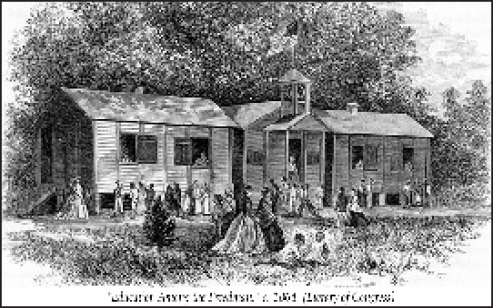

Education was the key to Reconstruction success and nation building. On the heels of the soldier came the Yankee teacher, who used, according to Henry Highland Garrett, “the spelling book, the Bible, and the implements of industry” as weapons of ideological war, and “schoolhouses and the Church of Christ” as forts. It is no surprise that Radicals such as O.O. Howard (known as the “Christian Soldier”), national superintendent of the Freedmen’s Bureau and author of Our Christian Duty to the South (1866), and Superintendent of Bureau Education John W. Alvord, in his biannual reports, considered education as the cornerstone of Reconstruction and recommended compulsory attendance. John Eaton, superintendent of Tennessee public schools (1867-69), agreed: “the State [of Tennessee] protects itself” when demanding school attendance.

The soldiers in this ideological war came from various backgrounds and had various levels of commitment. Many blacks did indeed establish schools, especially in the rural areas, and sought small donations from northern missionaries and local Bureau agencies. Some former Confederates even taught in public and Bureau schools, and more than a few white Southerners supported public education. (Granted, there was more local control of schools at the time.) Still, most educators hailed from above the Mason-Dixon line. Of the 9,503 teachers in Southern freedmen schools in 1869, approximately 5,000 left family and friends in the North and traveled south mainly to be missionaries in what many believed to be a pagan land. Many were Radicals, militantly devoted to abstract ideas such as positive liberty, and worked to establish a Republican Party in the South. Their numbers, as Revisionists argue, were much larger than previously thought.

Although concerned with teaching numbers and letters, Radical educators considered socialization and civic instruction most important. “Teachers . . . should not drill in mere technical scholarship,” wrote John W. Alvord. For what America most needed, argued Reuben Tomlinson, the superintendent of the South Carolina Bureau, was an “intelligent and loyal population.” A “proper education” eliminated a need for martial law and judicial activism, for children would be molded into Puritans, whom Henry Ward Beecher defined as promoting “the welfare of the state and want[ing] public affairs conducted in accordance to morals and religion.” A “proper education” also incorporated the Republican emphasis on free labor and ensured that freedmen evinced “Christian virtues” and demonstrated an ability to make a profit. Therefore, missionaries chose textbooks to inculcate “patriotic character” and create a “moral, virtuous, and Christian people” that served “the purposes of truth and progress.” To accomplish their goals, educators taught not only thriftiness, punctuality, temperance, industry, and sexual purity but “proper” manliness and domesticity, cleanliness and dress, and food preparation and house construction. For a while, individual instructors chose their own texts. But the decentralization of curriculum contributed to conflicting interpretations of American and Christian values, so, in some states and localities, the standardization of texts was encouraged.

Sometimes curricula included a conspicuous partisan import. Radical Republicans worked to establish their party in the South and considered freedmen, according to historian John Hope Franklin, to be the “best hope for building and maintaining a strong political organization that would keep the Radical in power.” In freedmen’s schools, children commonly learned to venerate Abraham Lincoln and occasionally made resolutions that endorsed Republican candidates for local and state offices. As John W. Alvord writes, the purpose of schools was to “produce a fraternity of feeling with us among the people, especially the common classes.” What they seemed to have wanted, however, was a republicanism that demanded obedience instead of participation.

When Northerners arrived in the South, they met freedmen who exhibited an intense desire to learn and to educate their children. Traveling across the South, J.T. Trowbridge saw freedmen “starv[ing] themselves and go[ing] without clothes” so that their children might attend school, and Bureau agents were impressed by large classes (sometimes nearing 300 students) working quietly and diligently. In well-run schools, many children appreciated their teachers for their labors and for being “true, earnest, and consistent friend[s].” Many blacks traveled for miles each day to attend school, and more than a few adults attended night school after a hard day’s work. Some isolated communities hired teachers, black and white, with only rudimentary knowledge. Financial circumstances, however, dictated that many freedmen attend only Sabbath schools, where Northern missionaries taught them the same Christian duties and American values that they would have learned in Bureau and missionary day and public schools.

In these schools, black students were told that their parents still succumbed to vices acquired during bondage; therefore, they should be beacons in a spiritual world of darkness and shun not only alcohol and tobacco but exuberant worship and incorrect parental instruction (in other words, whatever contradicted Radical Republicanism). In large numbers, younger children joined such clubs as the Vanguard of Freedom and the Band of Hope and pledged to resist all manner of temptation while holding their peers accountable. For not smoking, drinking, or gambling, young members earned certificates and ribbons and, most of all, the teacher’s praise. (It is not surprising that young black ministers during the 1880’s fervently promoted temperance.) Still, continued alcohol use particularly troubled missionaries. Some children saw and heard their parents laugh when Bureau agents asked them to sign O.O. Howard’s temperance pledges.

On the other hand, white Southerners were more ambivalent toward freedmen and public schools. Believing that they would personally benefit from the fruits of public education, more than a few whites supported it. Some were even on its payroll. In 1866, many white North Carolinians taught rural black schools, and a former Confederate lieutenant taught a Fayetteville school, to name just two examples. Other whites reacted violently. Although congressional committees never found firsthand evidence, it is not unreasonable to deduce that unreconstructed Southerners were responsible for the torching of schoolhouses and assaults on male teachers. Not coincidentally, many of the arsons and beatings occurred in predominantly Unionist areas, where antiblack rhetoric abounded.

The number of school arsons and assaults increased dramatically in 1868. Before then, far less violent opposition to freedmen’s education existed. Indeed, many whites, as DuBois writes, harshly criticized the establishment of freedmen schools. But disapproval does not mean violence. The worst a superintendent in Florida could report in 1866, for example, was that “in no case have the people shown a willingness to render us any assistance.” It must be remembered, too, that Bureau agents were required to report “outrages”—and did so in great detail. Many times, however, agents recorded that “Harmony and quiet prevail.” Good reports (or the lack of bad ones) indicate that freedmen in many places attended school without fear or interruption. In the fall of 1867, sentiments started changing, and, in the election year of 1868, violence abounded. After the election, violence subsided, and, following 1870, sources record even fewer “manifestations of opposition.”

So, why the sudden increase in violence? Chiefly, it was because white Southerners by and large opposed the use of schools as an arm of the Republican Party. U.S. Gen. John Tarbell testified to Congress in 1866 that Southern whites were not, by and large, “bitter against individual Northerners.” They even welcomed Northern businessmen who assimilated into local communities. They were not necessarily against freedmen education—or segregated public education, for that matter. They did, however, despise educators and missionaries instilling a Puritan mind-set in their children or turning schools into young-Republican clubs. They also condemned the Radical Republicans’ conflation of the state and Christianity and its influence on the schools and public life. The editors of the conservative Memphis Appeal, for instance, called Northern religious leaders “unchristian” for fomenting revenge even while Union and Confederate generals had let “by gones be by gones.” “We neither want clergy to act as our law-givers,” the editors continued, “nor the Statesman to give lectures in theology. It is a remarkable fact that the more sanctimonious the man, the more devilish the tyrant.”

Education reform involved more than schoolhouse construction and instruction, however. Labor and apprenticeship contracts reinforced what educators taught and ensured that those unable to attend school learned the American values of hard work and thrift. Bureau agents looked for employers who could foster “the moral and mental improvement” of the apprentices—that is, conformity to Northern values. Above all, agents wanted to find masters who taught children to be good citizens. Frustrated with unsuccessful searches for masters able to teach a “profitable trade,” many agents resorted to placing children with farmers. Children pledged to “faithfully serve” their Bureau-approved masters and subjected themselves to their “authority and control” in “all respects.” Employers, in turn, pledged to provide for apprentices and teach them “proper morality.”

Bureau agents and missionaries worked to redefine the family, too. The Radicals never passed opportunities in churches and schools or during home visits to tell freedmen how to live. Parents were urged to avoid adultery and provide for their children—good values, no doubt—but disagreements emerged concerning such activities as playing cards, or regarding compulsory school attendance. Many freedmen dismissed this condescending paternalism, and rural parents in particular preferred children to help out on the farm during August and September. Black parents were encouraged to instruct children to work hard, deposit savings into the Freedmen’s Bank, or donate to the missionary-outreach programs of their teacher’s denomination. Economic progress, parents learned, was possible because the Great Emancipator, who had preserved the Union, had given them opportunity.

In the Reconstruction South, Radical missionaries worked with the Freedmen’s Bureau in various efforts to teach black and white children not only the three r’s but a new definition of a “good American,” one that was an unnatural hybrid of statism and Christianity. The Yankees had come to rescue a region from its backwardness and heathenism. This included eradicating secessionist thought and steering black and white Southerners on the trajectory toward Progress—a world where freedom was to be made universal by an American, humanitarian empire, revolving for the glory of God. However, as historian Susan Mary-Grant observes, the belief in a pagan or blighted Dixie says more about “the North’s self-image than it did about the reality of the South.”

Leave a Reply