“Behold,” said the Lord, “I send you forth as sheep in the midst of wolves.” With this statement and by the Testament of His Own Blood, Christ inaugurated the Age of Martyrs—the first 300 years of the Christian era during which, in Jesus’s words, “They will deliver you up to the councils, and they will scourge you in their synagogues; and ye shall be brought before governors and kings for My sake, for a testimony against them and the Gentiles” (Matthew 10; 17-18).

Christianity had enjoyed an initial status of religiu licita in the eyes of the Roman government, during the reigns of Tiberius (under which our Lord was crucified), Gaius Caligula, and Claudius. The Romans, as conquerors, largely followed a policy of toleration when it came to conquered peoples and their religious cults, requiring only that their subjects admit the Roman gods—including (eventually) the emperors—into their local pantheons. This bit of ingenuity defused the potential conflict that could result from a forced breech of local tradition. Ancient Judaism (before A.D. 70) was among the sanctioned religions, and Roman officials regarded Christianity as a sect of Judaism.

No Roman citizen had greater hatred for this heretical sect than Saul of Tarsus. Before his conversion, Saul, “breathing out threatenings and slaughter,” led the angry mob in Jerusalem against St. Stephen, and, after his conversation, St. Paul’s efforts in Asia Minor and Greece helped to “draw a line of demarcation between Christianity and the Judaism of the synagogue.” Public hostility toward the new sect stemmed from what Edward Gibbon condescendingly referred to as “the first but arduous duty of a Christian to preserve himself pure and undefiled by the practice of idolatry.” In segregating themselves from the rituals of everyday life, gentile Christians become nuisances to their fellow citizens. In addition, their message—their “good news”—demanded the bold proselytization of their pagan neighbors. Ultimately their condemnation of paganism, no matter how discreetly expressed, aroused a public hatred that later made Christians fodder for the Circus. The first expression of this hatred, however, came in the form of rumors about the practices of the Christians, whose Holy Eucharist was misinterpreted as cannibalism.

Bv the time SS. Peter and Paul were in Rome in the early 60’s A.D., public sentiment toward Christians was so negative that the “fiery trial” predicted by St. Peter seemed inevitable. The great fire of Rome in A.D. 64 ignited this ideological powder keg. Contrary to popular belief, the Emperor Nero probably did not set the fire. However, when that rumor began to spread among the public, Nero needed someone to finger. According to Tacitus,

Nero substituted as culprits and punished with the utmost refinements of cruelty, a class of men loathed for their vices, whom the crowd styled “Christians” . . . First, then, those who confessed themselves Christians were arrested; next, on their disclosures, a vast multitude were convicted, not so much on the charge of arson as for hatred of the human race. And their death was made a matter of sport: they were covered in wild beasts’ skins and torn to pieces by dogs; or were fastened to crosses and set fire in order to sen’c as torches by night when daylight failed.

St. Clement, the bishop of Rome in the 90’s, records that it was near this time that St. Peter “went to the place of glory appointed for him,” while St. Paul endured for but a little while longer, before “departing thus from this world.” Peter was crucified upside down on Vatican Hill, where his bones now rest—the place where Constantine located his “trophy.” St. Paul was beheaded—”poured out like a drink offering”—having “finished the course” and “kept the faith.”

The early success of Christianity seems to have caused an increase in persecution. Domitian (AD. 81-96) smelled insurrection when his cousin, Flavius Clemens, and his wife, Domitilla, refused to burn incense to him and acknowledge his title—dominus et deus noster—which he had taken to himself out of jealously for his deified father and brother. This action led to Domitian’s identification of Christianity with “atheism”—a charge that would stick throughout the Age of Martyrs. Flavius Clemens—also a consul—was one of many that Domitian executed for “crimes against the state,” and Domitilla was exiled.

The greatest of Roman emperors, Trajan, set the first official policy of persecution for Christianity, although during his reign (A.D. 98-117) this policy was only sporadically enforced.

Christianity had become a problem in Bithynia, and the governor Pliny, who was also Trajan’s friend, asked for a ruling on different aspects of the problem. Should women and the aged be executed alongside the young men? Should a person’s mere embrace of the name “Christian” be enough to warrant a death sentence, or must he be guilty of a legal violation—say, refusing to burn incense to the Roman gods? These were questions only the Augustus could answer.

Trajan’s answer was conservative, balancing the law against equity and common sense. “No universal rule,” he said, “to be applied to all eases, can be laid down in this matter.” Trajan speaks with administrative indifference: “They should not be searched for; but when accused and convicted, they should be punished; yet if any one denies that he has been a Christian, and proves it by action, namely, by worshipping our gods, he is to be pardoned upon his repentance.” He goes on to say that anonymous accusations against Christians are to be deemed inadmissible in court because “they are contrary to our age.”

One effect of Trajan’s ruling was to define the assembly of the Church as an illegal club, one of the forbidden collegia or sodalitas that threatened imperial solidarity. Churches erected buildings, and Christians enjoyed a certain level of freedom in their worship, but they were subjected to molestation whenever a natural calamity, border strife, or petty bickering occurred. Tertullian, in his Apologiae, described this policy as both “lenient and cruel.”

The persecutions continued under Hadrian (A.D. 117-n8), though with less fanfare and fury. Hadrian seemed to hate Judaism—with which he was more familiar—more than Christianity. In Jerusalem, he built temples of Jupiter and Venus over the site of the Temple and at the place of the Crucifixion. A man of scholarship and reason, Hadrian was the recipient of some of the first Christian apologetic writings—those of Quadratus and Aristides—though it is doubtful he ever read them.

Under his successor, Antoninus Pius (A.D. 138-161), who served as high priest in the Roman temples, the Church of Smyrna and its great bishop, St. John’s beloved disciple Polycarp, were persecuted. It was Smyrna that St. John admonished, “Be faithful unto death.” When faced with the stake at age 86, he refused to avail himself of clemency: “Eighty and six years have I served Christ, nor has he done me any harm. How, then, should I blaspheme my King who saved me?”

Marcus Aurelius, the Stoic emperor (A.D. 161-180), might have been more sympathetic toward the Christian faith, since the Christians exhibited the muted calm in the face of death that was so prized by the Stoics. However, Toronto, Marcus’s tutor, had taught him to despise this bravely, since it was based upon a hope of future personal reward in the heavenly kingdom. The philosopher-emperor believed that Christians were acting irrationally by boldly confessing their faith in the hour of trial. Marcus even issued an edict forbidding the promotion of any philosophy that sought to change the moral actions of individuals based on fear of a deity.

A.D. 166 marks the beginning of the greatest terrors under Marcus Aurelius. It was called an annus calamitosus: The Tiber flooded, and there were several earthquakes in the western portion of the empire. Crop failures and plague in Gaul, coupled with raids from barbarians, caused great anxiety, and Marcus allowed his governors to quell the superstitions of their subjects by slaughtering Christians.

In Rome, the greatest of the early apologists, Justin, was beheaded, along with six others, in the year of calamity. His immeasurable contributions to the Church include his Dialogue with Trypho the Jew, in which he explains Christ’s presence on every page of the Law and Prophets, and the records of his public trial and debate with the cynic Crescens. Standing before the tribunal of Rusticus, he refused to talk his way out of his sentence, saving only that he desired “nothing more than to suffer for the Lord Jesus Christ: for this gives us salvation and joyfulness before his dreadful judgment seat, at which all the world must appear.”

Septimius Severus (A.D. 193-211) restored order after the follies of Marcus’s son Commodus and the civil wars that followed his murder. Severus issued the first edict that actually forbade conversion to Christianity”. Leonidas, the father of Origen, was beheaded as a result of the dissemination of the edict in Alexandria. Tertullian wrote his Defense of Christianity in Carthage at about this time, in which he lamented: “If the Tiber rises to the walls or if the Nile fails to rise, straightway the cry arises: ‘The Christians to the lions!'”

A quarter-century of peace under Alexander Severus (whose mother was taught by Origen) and Philip the Arab had only been interrupted by the brief reign of Maximin the Thracian, who in a frenzy had executed a handful of clergymen in the vicinity of Rome. During this calm, thousands throughout the empire converted, and popular myths about cannibalistic, seditious Christians began to fade. However, the great tribulation was at hand, as barbarians from the north and Persians from the east would force the emperors in Rome to make every effort imaginable to preserve unity. This included a vigorous return to the Roman pagan religion—an attempt to mend the ideological seams of the once-great empire. The result, ultimately, was the triumph of Christianity as the unifying ideology that would replace paganism.

The great tribulation came in three waves under three soldier-emperors: Decius, Valerian, and Diocletian. Despite their zeal for empire, they were not megalomaniacal, as was Domitian, or criminally insane, as was Nero. They were simply trying to recover the glory that was once Rome.

Under Decius, the first wave poured out of Rome like a torrent in the year 25O, when he issued his edict to the governors to persecute all who would not burn incense to the Roman gods. He ordered the bishops killed and peasants placed on trials. Standing before the magistrate, these fearful converts could sign certificates called libelli that certified their renunciation of Jesus Christ and bore witness to an act of idolatry—the burning of incense to Decius. The Church was faced with the challenge of excommunicating these lapsi, then dealing with those who later repented and sought reinstatement.

The political dimension of the persecution came even more pronounced in the reign of Valerian (253-260), who was persuaded that the Christians were treasonous conspirators in league with the Persians. In 257, upon news of the Persian invasion of Syrian Antioch (long a stronghold of the Church), he issued an edict forbidding Christians to meet for worship or visit their cemeteries throughout the empire. Many Christians in Rome fled “to the hollows” (ad catacumbas) near the church of St. Sebastian on the Appian Wav. Here, they buried their dead in the famous underground tunnels.

Another edict of Valerian, issued in 258, demanded the execution of any man convicted of being a Christian priest, degraded a Christian senator or soldier from his rank, and forced others into exile—often to the war-torn fringes of the empire. Cyprian of Carthage and Pope Sixtus II were executed immediately.

The imprisonment of Valerian on the Persian battlefront in 259 marked the beginning of four decades of peace and prosperity for the Church, during which a few great houses of worship were built and many more came to the faith. But the increased threat of massive foreign invasion led to the greatest of all persecutions, the last of the Age of Martyrs, under Diocletian.

Diocletian spent his reign defending the empire from foreign enemies and attempting to reestablish unity within its borders. Christianity, which was both divisive and transnational, appeared an obstacle to his efforts. For 20 years, there had been no need to carry out the policies of Decius—until 503, when war with the Persians threatened afresh. Galerius had become violently anti-Christian, believing his wife’s Christianity (as well as that of Diocletian’s wife) to be a stain of dishonor on the imperial family. On February 25, 305 (the feast of Terminalia), he convinced his father-in-law to order the destruction of all Christian meetinghouses throughout the empire. The clergy were arrested, and the Scriptures were burned. Then, in 304, the policy of Decius was reinstated: All throughout the empire—including Diocletian’s wife and daughter—would have to burn incense to the Roman gods or be put to death.

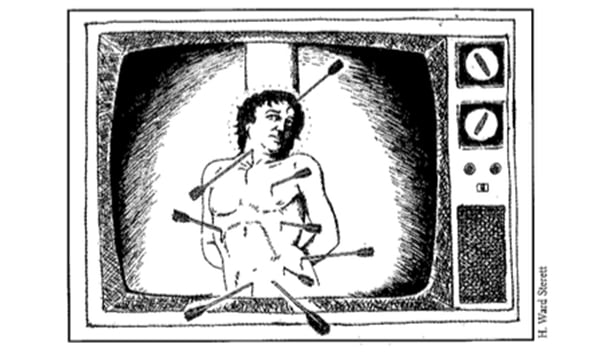

The most severe persecution was enacted under the auspices of Galerius and Maximin, and soldiers were instructed to force the children of those on trial for Christianity to eat sacrifices made to Diocletian. Thousands were crucified, put to the rack, thrown before beasts, or beheaded. Eusebius described with horror his presbyters being “torn to pieces” in the amphitheater in Caesarea. Toward the end of the great tribulation, he observed the weariness of the Romans: “The bloody swords became dull and shattered; the executioners grew weary, and had to relieve each other; but the Christians sang hymns of praise and thanksgiving in honor of Almighty God, even to their last breath.”

The Age of Martyrs came to an end under the sign of the Cross in 311. Many downplay the era, saying no more than 3,000 wore the crown of life during these 300 bitter years. Gibbon, for one, mocks the austerity of the Christians of whom St. John said, “They loved not their lives unto death.” Others bristle at the legendary embellishments of some of the martyrologies. Modern historians sympathize with the sanity of Trajan, Marcus Aurelius, Decius, and Diocletian: These were noble Romans who sought to preserve their kingdom.

So what are we to make of the martyrs and their age? They, too, have a kingdom—an unshakable kingdom that is “not of this world.” Theirs is the crown of life, and though they cry out, “How long, O Lord, before you avenge us,” theirs is the beatific vision.

Still, one might ask, would burning some incense and reciting a meaningless oath have jeopardized that? Would it not be better to live longer, to remain with one’s family instead of depriving them of a father, a mother, a son, or a daughter? The possibility of personal glory and the promise of perpetual memory aside, the martyrs were singularly focused on the word of their Savior and the promise of eternal life:

Whosoever therefore shall confess me before men, him will I confess also before my Father which is in heaven. But whosoever shall deny me before men, him will I also deny before my Father which is in heaven.

They knew the word of their Lord, and for them, there was no other option but to confess His Name in the hour of trial. When the persecutions are renewed, how many of us will follow their example?

Leave a Reply