In the early years of the second half of the 20th century, some time between Stalin’s death in March 1953 and the Hungarian uprising in October 1956, it had ceased to be fashionable for Western leftist intellectuals to be uncritically supportive of the late Soviet dictator and his bloody legacy. The search was on for a communist role model with, well, not necessarily “a human face,” but rather a dashing personality that could appeal to the bourgeois bohemians of la Rive Gauche, Hampstead, and the Upper East Side.

In Britain, a whole generation of scholars coming into their prime at that time (William Deakin, Elisabeth Barker, Basil Davidson, Phyllis Auty, Stephen Clissold, etc.) devoted their careers to the construction of the myth of Josip Broz Tito. The Yugoslav dictator was portrayed as a fearless wartime resistance leader who dared say no to Stalin in 1948, and thereafter proceeded to build a “multiethnic socialist society” based on “workers’ self-management” at home and “non-alignment” abroad. The myth was some light years away from the grim reality of Tito’s police state, but that did not matter to its purveyors. What upset their applecart was the emergence of Fidel Castro as the iconic figure of the smart gauchistes, especially in France.

Castro’s revolution started with the usual bloodbath: 18,000 executions in 1959-62, in a nation of seven million, was the equivalent of 850,000 death sentences in today’s United States. That did not worry Jean-Paul Sartre, who went to Cuba in the 1960s to meet Castro and enthused over what he called the island’s “Russoism,” its “direct democracy and warm lemonade.” Sartre also met Castro’s fellow mass-murderer Ernesto “Che” Guevara, whom he called “not only an intellectual, but also the most complete human being of our age . . . the era’s most perfect man.”

The rest is history. As late as 1990 a popular French novelist, Jean-Edern Hallier, gushed about Castro as a “medieval knight” whose “island is too small for him,” and his historic mission, a veritable embodiment of the “universal spirit of resistance,” a man “who has never accepted the discovery that human nature is not good.” Here was the key to understanding the Western leftists’ pathology: Since the Enlightenment they have been trying to escape the immutable givens of human nature and social conflict, to assert that mankind is on the trajectory of linear historical progress, and to demonstrate that human nature is capable of being corrected through politics, education, and indoctrination. If the process required liberating tens of thousands of Cubans of their lives or liberty, or sending at least one in ten into exile, and reducing the third most prosperous Latin American country of 1952 to the bottom of the hemispheric scale . . . still, the price was well worth paying.

Like all other communist tyrants, Castro did not use terror to carry out his revolution; he used the revolution as a means of introducing the reign of terror. He also tried to export it: “The duty of a revolution is to make revolution.” In the process he played a destructive bit part in the most dangerous crisis of the Cold War, urging the Soviets to risk armed conflict with the United States, rather than agree to remove nuclear missiles from Cuba. He was bitterly disappointed when Khrushchev eventually blinked, in October 1962, and got involved in a series of “people’s liberation struggles” in Africa and Latin America, which cost 14,000 Cubans their lives between 1965 and 1979. Yes, he was punching above his weight—to the detriment of his impoverished nation, and often to the exasperation of his Soviet sponsors.

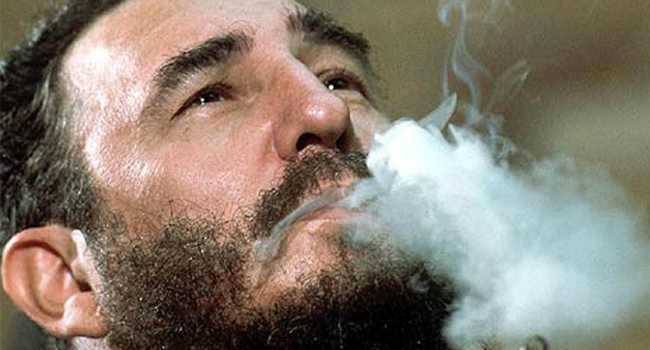

In the end, there is no Castro legacy. Fidel Castro had ceased to matter long before his brother Raul—now 85—took over eight years ago. In the fulness of time, Cuba will be de-Castroized, and its talented people will drag themselves out of the present abject poverty created by six decades of state central planning. The beard, the fatigues, the cigar, the egomania, will be duly consigned to the dustbin of communist utopia, the scourge which has cost so many so much over the past century.

Leave a Reply