Bernard Malamud: The Stories of Bernard Malamud; Farrar, Straus & Giroux; New York.

Isaac Bashevis Singer: The Penitent; Farrar, Straus & Giroux; New York.

Morality is religion’s province. Contemporary secularists do not see this, averting their eyes from the religious sources of their own moralities. Such aversion makes a kind of sense; deprived of any metaphysical foundation, secular morality can only rest on a physical one, and modern physics, chemistry, and biology are morally unpromising. Looked at hard, modern secular moralities dissolve into more or less appealing immoralisms, though many people prefer not to notice. Even ancient philosophers, celebrated or condemned for their teleology, never quite offered rigorous proofs that nature issues directly in morality. Custom and opinion, compacted largely of accident and artifice, seem to contribute more.

Moral commandments animate Judaism. Hebrew has no word for “nature.” Judaism rejects accident for Providence and abhors the art that produces graven images. Today’s Jews confront men animated by modern science, the art of using nature to conquer nature, a human providence. The non-Jews Jews confront are therefore more profoundly unJewish than any other non-Jews in history. Bernard Malamud and Isaac Bashevis Singer write very differently, but each responds to the confrontation of Jews with modern non-Jews by upholding the Jewish tradition of moral seriousness.

Malamud has collected 25 of his short stories, all but two of which appeared in previous books. In his preface Malamud write that literature “values man by describing him” — a remark that smoothly mediates between literary realism and concern for morality. The men and women described here inhabit life’s margins. Retired, poor, grieving, they “suffer from [their] health,” as one of them puts it, a phrase that makes “health” synonymous with being sick. Their vulnerability allows Malamud to illustrate the moral themes that fascinate him: charity, guilt, love, and faith.

In “The Bill,” a married couple who own a store extend credit to a neighbor because “if you were a human being you gave credit to somebody else and he gave credit to you.” But the man who gets the credit resents them for it, feels guilty, and never pays his debt. The protagonist of “Black Is My Favorite Color” tries to extend charity and love to blacks, who reject it or fail to return it. “[T]he language of the heart is either a dead language or else no one under stands it the way you speak it,” he laments. Nor are non-Jews the only proud ingrates, Jews faultlessly charitable. “The Jew bird” is a parable about Jewish resentment of victimized Jews; in “Man in the Drawer” an American Jewish writer resents the gift of a manuscript from a desperate Jewish colleague in the Soviet Union.

The relation between giver and recipient obtains in the relation between an artist and those who care for art or believe they care. “Rembrandt’s Hat ” one of Malamud’s best stories, features an art historian who thinks of a sculptor, “All I have is good will toward him. “Just so — but good will is not enough. After unintentionally offending the sculptor by comparing the artist’s hat to one in a Rembrandt self-portrait, the historian feels “surges of hatred.” Months of feuding pass before the historian takes another look at the Rembrandt painting.

In his self-created mirror [as distinguished from mirrors held up by historians and critics J the painter beheld distance, objectivity painted to stare out of his right eye; but the left looked out of bedrock, beyond quality. Yet the expression of each of the portraits seemed magisterially sad; or was this what life was if when Rembrandt painted he did not paint the sadness?

The historian also notices a simple fact: he had misremembered Rembrandt’s hat, which does not closely resemble the hat the sculptor wears. Those who would partake of what artists give us must learn empathy, not only judgment; without empathy attention fails, causing inaccurate perceptions and false judgments. The historian reconciles with the sculptor, who wears his hat” like a crown of failure and hope”-failure, because he is no Rembrandt, hope for achieving something fine.

“Art celebrates life and gives us our measure,” Malamud writes. The celebration is no more direct in his stories than in Rembrandt’s paintings. Guilt can literally bring death, as in “The Jewish Refugee,” the story of a German-Jewish critic and journalist who believes that his German wife, left behind, was secretly anti-Semitic. He commits suicide after learning that she had converted to Judaism and was murdered by the nazis. But Malamud does not join with Nietzsche and his epigones in celebrating life without guilt. “The Death of Me” shows non-Jews who quarrel and who come to hate each other bringing death to a Jew. “Life Is Better Than Death” ironically portrays a young widow whose affair ends in pregnancy and desertion. Malamud’s most revealing title plays on a stock’ expression, “The Cost of Living.” By describing the slow impoverishment and bankruptcy of an old-fashioned grocer, Malamud insists on life’s physical and spiritual costliness.

Only a few of his people see what makes life worth its cost: fidelity, that combination of faith and love. “The First Seven Years” depicts the reciprocal fidelity of a man and a woman by echoing the story of Jacob and Rachel. Fidelity between human beings mirrors the even more difficult fidelity between a human being and God. The theme of giving and receiving is here, too, as God gives life and the moral standards governing it, forcing men to choose between gratitude and resentment.

Malamud sees both the humor and the seriousness in this. “Talking Horse” concerns Abramowitz, a circus performer who doesn’t know if he’s a talking horse or a man trapped inside the horse, and his owner, Goldberg, who “doesn’t, like interference with his thoughts or plans, or the way he lives, and no surprises except those he invents.” “The true pain,” Abramowitz says, “is when you don’t know what you have to know.” He comes to suspect that “Goldberg is afraid of questions because a question could show he’s afraid people will find out who he is”: “Somebody who all he does is repeat his fate.” The exceedingly human Abramowitz demands his freedom and gets it. He struggles part of the way out of his horse-body and becomes “a free centaur,” neither beast nor Goldberg.

One of the few characters whose profession Malamud declines to tell us is Mendel, the loving father of an idiot son. Dying, Mendel wants to get his son on a train to California, where he can live with a relative. Ginzburg the ticket collector blocks them; his gaze terrifies Mendel, who dares to struggle for his son.

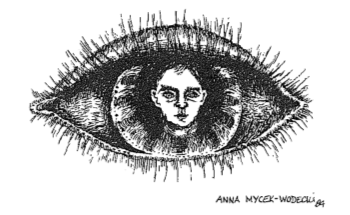

Ginzburg, staring at himself in Mendel’s eyes, saw mirrored in them the extent of his own awful wrath. He beheld a shimmering, starry blinding light that produced darkness.

Ginzburg looked astounded. “Who, me?”

God recognizes His own cruelty because he can see it reflected in the eyes of a human being, His most notable creation. Only then He shows mercy, lets the son be saved.

Salvation and freedom obsess Singer’s protagonist as well. But whereas Mala mud’s stories express opinions indirectly, requiring interpretation, Singer allows his protagonist to speak almost directly for Singer. The opinions expressed contradict, even denigrate, the opinions of the dominant “culture” of our time. This may account for the book’s unusual publishing history.

The Penitentappeared in serial form in 1973, then as a book one year later. Farrar, Straus & Giroux published it in English in 1983, surely an unusual delay in view of the author’s prestige. According to the dust jacket copy, although “the novel was immediately recognized by its readers as one of Singer’s most serious, and perhaps finest, works,” some critics “predicted it would never be translated” “because of its inwardness.” “Inwardness?” No: Jewishness was the real offense — and not the Jewishness that accommodates itself to the world and meets with toleration from all but the worst anti-Semites. Singer presents us with a Jew who speaks for the Judaism that spurns the ways of this world, and he insists that we listen to this Jew respect fully. Singer is right to insist. With his protagonist, Joseph Shapiro, he shows a contemporary man reconstructing lost faith in God.

Shapiro briefly recalls his early life as a young “progressive” from a Polish rabbinical family. After surviving World War II, he married, came to America, and made his fortune in real estate. “When a person makes a good deal of money but lacks faith, he begins to concern himself with one thing: how to squeeze in all the pleasure possible.” Adultery follows, of course; “the loose female has become the deity of America.” In an indirect way, so does tolerance of the violent crimes of those who want quick gratification: “In America, as in Sodom, the perpetrator went free and the witness rotted in jail. And all tl1iswas done in the name of liberalism…. Everyone knows this, but try talking about it and you’re called the worst names.” His life eventually caused Shapiro to suffer spiritual and physical nausea. His nausea is not to be confused with that described by Sartre (which was essentially borrowed from Nietzsche), for it leads him to the opposite conclusion:

all modern philosophy has a single theme: we don’t know anything and cannot know anything …. But to what did this lead? Their ethics weren’t worth a fig and committed no one to anything. You could be versed in all their philosophies and still be a Nazi or a member of the KGB.

The likes of Heidegger, Sartre, and Merleau-Ponty could object to this, but Shapiro left wife, mistress, and business, and flew to Israel: “The Jew in me suddenly gained the courage to spit at all the idolatries.” He saw many of the same idolatries in Israel. Looking at books and posters in Tel Aviv, he thought: ”Yes, the Enlightened have attained their goals. We [Jews] are a people like all other peoples. We feed ourselves the same dung as they do.” Communism offers no better “culture” than capitalism does, and it adds tyranny. At a leftist kibbutz portraits of Lenin and the anti-Semite Stalin hung in the “Culture House.”

Shapiro contrasts modern “culture” with the learning attained in a Hasidic study house in Jerusalem. He goes so far as to charge that “All the heroes in worldly literature have been whoremongers and evildoers,” citing Anna Karenina, Raskolnikov, and Taras Bulba. “Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, Dante’s Divine Comedy, Goethe’s Faust, right down to the trash aimed at pleasing the street louts and wenches, are full of cruelty and abandon.” To those who would reply that the Old Testament contains its share of vice, Shapiro agrees: “The Scriptures were a great beginning, an enormous foundation, but the Jews of the Scriptures were, with few exceptions, still half Gentiles.” The Talmud contains more refined spirituality: “The Jew has attained his highest degree of spirituality only in the time of the Diaspora,” and today’s genuinely religious Jews are “Jewry’s greatest achievement.”

Shapiro sets his way of life against that of a young woman he met on the plane to Israel. Priscilla, “ashamed of [her] Jewishness since childhood,” engaged to be married to another secularized Jew, quickly seduces Shapiro. They meet again after several months in Israel. The last two chapters consist of a dialogue between them. Priscilla argues for atheism. As with all such arguments, hers logically justifies no more than agnosticism. Shapiro replys that morality requires choice, and that her choices imply humanism, which “doesn’t serve one idol but many idols,” all of them eventually destructive of the very pleasures they promise. Even if the Jewish God is an idol, the morality He commands brings no destruction. Morality leads to faith, not the other way around.

In the “Author’s Note,” written for this edition, Singer “cannot agree with [Shapiro] that there is a final escape from the human dilemma” because “a total solution would void the greatest gift that God bestowed upon mankind — freedom of choice.” But Shapiro never claims that his solution is total, that he has escaped from the human dilemma, as distinguished from the modern one. He explicitly insists on the Evil Spirit’s power and doggedness. A more telling criticism begins with noticing that morality finds support in non-Jewish religious practices also. If the quest for moral strength leads us to more than one path, we are not by any means “back where we started” but we are given pause.

There is also a practical difficulty. Shapiro’s highly spiritualized Judaism rejects the political and military aspects of Judaism seen in ancient and modern Israel. He praises the Diaspora because it removed Jews from the responsibilities and temptations of rulership; he says that “when it suits the Evil Spirit, he can become a fervent Zionist, a burning patriot.” Thus Shapiro speaks in the accents of martyrdom. Pacifist Judaism resembles pacifist Christianity. Here Singer’s charge of escapism would hit with force. Shapiro could reply, with other pacifists, that “God will fight for us,” if not in this world then in the next world, or in this world on the day of the Messiah. Paradoxically, this faith that begins with practice, with morality not theory, ends by dismissing the practical.

Singer concludes: The agonies and the disenchantment of Joseph Shapiro may to a degree stir a self-evaluation in both believers and skeptics. The remedies that he recommends may not heal everybody’s wounds, but the nature of the sickness will, I hope, be recognized. Throughout their careers, Singer and Malamud have served as careful diagnosticians, not merely as makers of refined entertainments. cc

Leave a Reply