There are numerous references to gold in the Bible. Gold was used to construct the ark and tabernacle (Exodus 25), adorned Solomon’s court (1 Kings 10), and is visible in Heaven in St. John’s Apocalypse (Revelation 4:4). Gold symbolizes value (Proverbs 8:10) and earthly wealth (Acts 3:6); among its many descriptors is “fire-tried” (1 Peter 1:7). But the Old Testament story of the golden calf is perhaps the best-known biblical reference to the mineral commodity. “Do not make anything to rank with me,” the Lord instructed Moses on Mount Sinai, “neither gods of silver nor gods of gold shall you make for yourselves.” While Moses was away, the Israelites fashioned a golden calf. Moses destroyed the idol after descending, whereupon “the Lord smote the people” for having made it (Exodus 20:23, 32:19-20, 35).

The golden calf was not cited by William Jennings Bryan at the Democratic National Convention in 1896 when he employed other biblical imagery to condemn the gold standard in support of bimetallism. “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns,” Bryan thundered. “You shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.” Modernist opponents of a role for gold in the monetary order, including economists and the journalists that amplify their opinions in popular media, trace their roots to Bryan’s speech, not to Scripture.

Bryan’s 19th-century speech defined the terms of the monetary debate in the following century, a point overlooked by proponents of a role for gold in the monetary order. Opponents, not proponents, are trying to “turn back the clock.” The public policy of Bryan’s speech can be summarized in five words: Gold restricts expansive monetary policy. Every argument against a role for gold in the monetary order is a variation on this basic theme. “The current world monetary system assigns no special role to gold,” economics professor Paul Krugman explained (Slate, November 23, 1996):

indeed, the Federal Reserve is not obliged to tie the dollar to anything. It can print as much or as little money as it deems appropriate. There are powerful advantages to such an unconstrained system. Above all, the Fed is free to respond to actual or threatened recessions by pumping in money.

Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke has acknowledged this point for years. “Countries on the gold standard” during the Great Depression, Bernanke observed in a speech at Washington and Lee University (March 2, 2004),

were often forced to contract their money supplies because of policy developments in other countries, not because of domestic events. The fact that these contractions in money supplies were invariably followed by declines in output and prices suggests that money was more a cause than an effect of the economic collapse in those countries.

Bernanke and other academics claim gold not only restricts central banks but deepens depressions and recoveries in countries that remain committed to it.

The question of a gold standard has reemerged early in the 21st century, against the economic backdrop of record trillion-dollar budget deficits that have failed to reverse, in the last two expansions, the postwar era’s weakest employment growth. These are the expansions under George W. Bush (November 2001 to December 2007) and President Obama (June 2009 to the present). Clearly, the current monetary policy, which excludes a gold standard, is not working. One sobering fact illustrates this point: National payroll employment has contracted by 2.1 million jobs (according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics) since February 2006, when Bernanke became Fed chairman. This is the reason gold has reemerged in the monetary debate; first, in best-selling books by U.S. Rep. Ron Paul (R-TX); and second, in the 2012 Republican Platform. The GOP, in a 283-word plank titled “Inflation and the Federal Reserve,” declares its support for establishing “a commission to consider the feasibility of a metallic basis for U.S. currency.” A similar panel established under President Reagan in 1981 “advised against such a move,” though a minority report influenced by Murray Rothbard advanced the issue. The GOP plank continues, “Now, three decades later, as we face the task of cleaning up the wreckage of the current Administration’s policies, we propose a similar commission to investigate possible ways to set a fixed value for the dollar.” The plank has been criticized by Matthew O’Brien in The Atlantic (“Why the Gold Standard is the World’s Worst Economic Idea, in 2 Charts),” which argues it did not lead to the price stability claimed by proponents.

Journalists opposed to a gold standard overlook several points conceded by academic opponents. “The gold standard appeared to be highly successful from about 1870 to the beginning of World War I in 1914,” Bernanke admitted in 2004. “During the so-called ‘classical’ gold standard period, international trade and capital flows expanded markedly, and central banks experienced relatively few problems ensuring that their currencies retained their legal value.” According to Bernanke, the gold standard was suspended during World War I because of trade disruptions and “because countries needed more financial flexibility to finance their war efforts.” Nobel economist Robert A. Mundell, a gold proponent, explained in a 2000 issue of The American Economic Review that “The twentieth century began with a highly efficient international monetary system that was destroyed in World War I, and its bungled recreation in the interwar period brought on the Great Depression, Hitler, and World War II.”

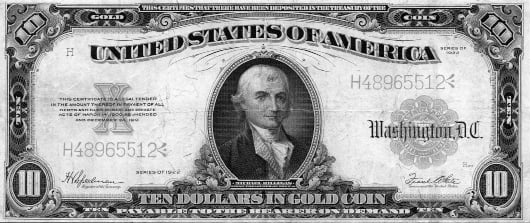

Mundell noted the classic standard “operated smoothly to facilitate trade, payments, and capital movements.” The “price level may have been subject to long-term trends but annual inflation or deflation rates were low, tended to cancel out, and preserve the value of money in the long run.” Interwar, the United States was on a gold-exchange standard until 1933, and a restricted pseudostandard until 1944. Postwar, gold played a key role in the Bretton Woods Agreement (1944-71), fixed to the dollar at $35 per ounce, with other nations’ currencies tied to the U.S. currency. The people, under the classic standard that ended with World War I, had the power to redeem money for the commodity. Under Bretton Woods, only central banks retained that power, until President Nixon closed the gold window on August 15, 1971, in response to the Vietnam conflict’s rising costs.

The correlation between military conflict and cessation of a gold standard is frequently lost on liberal opponents. A gold standard is a check on politicians’ power to engage in deficit spending. World War I, in Mundell’s description, made gold “unstable” because of deficit spending, which “pushed the European belligerents off the gold standard.” Gold flowed into the U.S. Treasury, “where the newly created Federal Reserve System monetized it, doubling the dollar price level and halving the real value of gold.” Opponents contend the interwar gold standard deepened the Great Depression. Proponents like Mundell maintain that the Fed engineered a dramatic deflation in the 1920-21 recession, “bringing the dollar (and gold) price level 60 percent of the way back toward the prewar equilibrium,” where it stayed until 1929. “The problem was that, with world (dollar) prices still 40 percent above their prewar equilibrium, the real value of gold reserves and supplies was proportionately smaller.”

Nixon’s suspension of a gold standard resulted in the 20th century’s highest inflation readings. (Lincoln’s inflationist monetary policy had a similar effect during the Civil War.) CPI averaged 8.5 percent annually between 1972 and 1981, with a 13.5-percent peak in 1980. Goods and services that cost a dollar in 1971 require $5.74 today, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Opponents like O’Brien in The Atlantic compare CPI during the interwar gold-exchange standard (1919-33) with monetary easing under Bernanke (2008-12), concluding there has been more price stability in the latter period. A more apt comparison is between the 1950’s (2.1 percent CPI) and 1960’s (2.5 percent) under Bretton Woods, and quantitative easing (2008-the present) under Bernanke (2.3 percent). There is, in fact, little difference in inflation rates.

Proponents who limit their definition of a gold standard to the classic standard era undercut the popular appeal of their movement’s strongest argument to the American people: Current monetary policy is not working. There are various examples of a gold standard: the classic and gold-exchange standards; the Bretton Woods system; the price rule advocated by supply-siders; and the commodity basket mechanism (including gold) discussed by U.S. Rep. Jack Kemp (R-NY), and others in Congress in the wake of 1970’s-era inflation. Proponents seeking to buttress their case with evidence from an establishment monetary figure need look no further than Alan Greenspan, the former Fed chair (1987-2006). An immediate return to a gold convertibility would create a serious problem: the large worldwide excess of fiat currency, especially U.S. dollars, as Greenspan noted in the Wall Street Journal (“Can the U.S. Return to a Gold Standard?,” September 1, 1981). The essay is rarely cited by proponents. Greenspan explained that one way to restore a gold standard would be for the U.S. Treasury to issue Treasury notes with the principal or interest payable in ounces or grams of gold:

With the passage of time and several issues of these notes we would soon have a series of “near monies” in terms of gold and eventually, demand claims on gold. The degree of success in restoring long-term fiscal confidence will show up clearly in the yield spreads between gold and fiat dollar obligations of the same maturities. Full convertibility would require that the yield spreads for all maturities virtually disappear. If they do not, convertibility will be very difficult, probably impossible, to implement.

The gold commission envisioned by the Republicans should examine Greenspan’s idea, along with Ron Paul’s suggestion to use gold as currency and the supply-siders’ proposal to adopt a price rule. The central bank, under a price-rule system, expands the money supply when the gold price decreases, and tightens when it increases. The same idea underlies the commodity-basket mechanism. A price rule can be formal (mandatory) or informal (discretionary).

Contemplating a gold standard is a search for honest money. The Bible proposes “true scale and true weights” (Leviticus 19:36), a call for honesty. The opposing view in ancient times was monetary debasement through sovereign coin clipping. Modern central banks like the Fed, according to Krugman, retain the freedom to “print as much or as little money” as “appropriate.” As long as central banks retain this power the American people will find it more difficult to achieve another biblical precept: “Owe no debt to anyone except the debt that binds us to love one another” (Romans 13:8).

Leave a Reply