Inflation is caused by American politicians and economists who both meddle in the economy and involve the nation in frequent wars.

Inflation is a serious problem in America, but few are willing to think seriously about its devastating effects or its underlying political causes. While both politicians and economists are to blame for rising inflation, their actions are intimately connected, each potentially responsible for negative consequences that can affect all of us. Still, politics is at the heart of the problem.

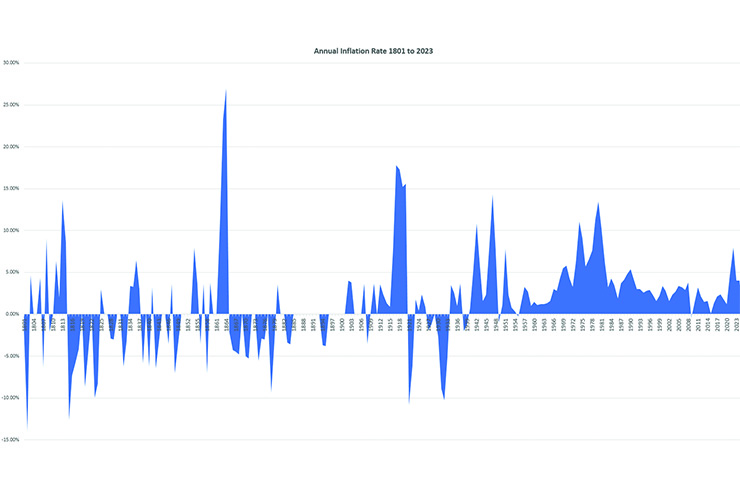

An important aspect of the political dimension, rarely discussed in mass media, is the relationship between war and inflation. The highest inflation rates in U.S. history have occurred during and around periods of war. There have been only 14 years since 1800 when inflation increased at double-digit rates, and nearly all of them were during war years. By contrast, there were 129 years of U.S. history when inflation either increased less than 2 percent, was unchanged, or even negative—virtually all of them peacetime years. As the chart above shows, zero or negative inflation is the norm in peacetime U.S. history by a wide margin.

While America is not currently in a war, it is funding a proxy war in Ukraine against Russia, and the effect is similar. Since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the United States government has sent more than $60 billion in military, economic, and humanitarian funding and equipment to the beleagured nation. It has allocated $113.4 billion in total aid, and in August President Joe Biden asked Congress to approve an additional $24 billion in funding, which has not yet been approved.

The result has been that the Consumer Price Index (CPI), which has been rising an average of less than 2 percent for many years, recorded a 6.5 percent increase in 2022, according to the U.S. Labor Department, its highest rate since 1981. The CPI is a decent measure of the human cost of inflation. It measures the average change in price for urban consumers of a basket of common goods and services. There were only 10 years since the end of World War II when inflation in America was as bad as it was in 2022. Six were in the last era of great inflation, from 1972 to 1981, when CPI increased at an average annual rate of 8.5 percent, which more than doubled the price of everything in a single decade.

Beyond the data there is the human cost. People have to eat. The same Labor Department release reported food prices increased 10.4 percent last year. They also have to drive, and to cool and heat their homes. Energy rose 7.3 percent overall, while petroleum prices skyrocketed. Fuel oil jumped 41.5 percent in 2022. Meanwhile, the spot price for the U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate crude oil barrel has reached around $90, a roughly 80 percent increase from $52 a barrel in January 2021. Car insurance rose 14.2 percent last year and medical insurance, 7.9 percent. PI remains elevated in 2023, increasing at a rate more than double the Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) 2.0 percent target.

In sum, Americans are paying more for life’s necessities, and they will be paying even more as inflation remains elevated. Various private sector economists and financial forecasters argue that inflation rates are actually higher than the government reports and that government statistics understate inflation’s true cost to consumers.

Fortunately, some households understand the idea of substitute goods. They substitute chicken for steak, turn down their thermostats, and buy smaller motor vehicles. But this only goes so far, as after-tax household income is also in free fall. The Census Bureau announced in September that inflation-adjusted median household income fell for a third straight year, declining by a steep 8.8 percent to $64,240 in 2022.

When prices go up, and incomes go down, people feel the pain and they make their pain known at the polls. There has been a great deal of partisan posturing and finger-pointing about the inflation issue, but little exploration by mass media at a fundamental level of either how bad inflation hurts Americans or why it is happening. Instead, Americans are told to trust a monetary consensus that fails them.

The highest inflation years in U.S. history were during the Civil War, when inflation went from zero immediately before the war to peak at 27 percent in 1864. Next were the years during World War I and immediately following, rising from less than 2 percent in the decade before the war to peak at 17.8 percent in 1917, the year the U.S. entered the conflict. During World War II, inflation didn’t peak until after the fighting stopped, at 14.4 percent in 1947. During the War of 1812, at 13.7 percent. And in the Vietnam War at 11.1 percent, in 1974. The high inflation of the stagflation years of the late ’70s and early ’80s, peaking at 13.5 percent in 1980, followed as a consequence of the Vietnam War.

During World War I, price controls did not prevent the CPI from rising at double-digit rates until 1921 when a deflation occurred. “The World War I era and its aftermath, 1917–1920, then produced sustained inflation unmatched in the nation anytime since,” the Labor Department’s Bureau of Labor Statistics wrote in a 2014 report. “Prices rose at an 18.5-percent annualized rate from December 1916 to June 1920, increasing more than 80 percent during that period.”

Price inflation was flat prior to World War II before increasing in 1942 to 10.9 percent after Congress passed the ironically named Emergency Price Control Act, which fixed maximum prices until war’s end in 1945. As the Bureau of Labor Statistics article notes, “World War II price controls were far broader and more effectual than previous efforts. Price controls and rationing dominated resource allocation during the war period.” But the government price controls also created secondary effects: price floors led to surpluses, while price caps resulted in shortages and even rationing. When the price caps were lifted after the war, CPI jumped.

The postwar period of peace was also an era of low inflation that was good for American workers and the broader middle class. “Labor never had it so good,” AFL-CIO union boss George Meany observed in 1955. Inflation remained largely below 2 percent until the Vietnam War, when it rose steeply, exceeding five percent in 12 years before finally falling to a rate less than two percent in 1986.

Economists abiding bad fiscal policy arguably bear more responsibility for inflation than politicians. The central bank’s domain is monetary policy, while fiscal decisions including tax-and-spend issues are the politicians’ realm. Yet monetary and fiscal policy do intersect and politicians who shrug this off are neglecting their duties. Fed Chairman William McChesney Martin once told a New York investment bankers meeting the central bank “is in the position of the chaperone who has ordered the punch bowl removed just when the party was really warming up.” The theory behind McChesney’s explanation is that preemptive Fed action is sometimes necessary to prevent inflation from growing roots.

In the real world, there have been episodes where the Fed continued to spike the punch by enabling politicians to pursue profligate fiscal policies. In 1965, President Lyndon Baines Johnson summoned Martin to his Texas ranch. LBJ pressured Martin to pursue easy monetary policy so his administration could advance its “guns and butter” agenda of increased spending for both Vietnam and the president’s Great Society programs. Martin acquiesced, as did his successor, Arthur Burns (1970-78), to demands from both LBJ and his successor, Richard Nixon.

Both episodes are discussed by Fed Chair Ben Bernanke’s book 21st Century Monetary Policy. Bernanke’s book describes the monetary-fiscal intersection under Fed Chair Alan Greenspan (1987-2006) who seemed willing “to reward with lower interest rates politicians who accomplished deficit reductions.”

Post-Greenspan, the treat pile expanded; the central bank pursued a liberal interpretation of the Federal Reserve Act’s Section 13(3), making “large-scale asset purchases” through quantitative easing. It’s no surprise the last federal surpluses occurred a quarter-century ago (1998-2001). Greenspan’s 2001 congressional testimony on fiscal policy appears surreal, in retrospect. In it, he raises the possibility “publicly held debt is effectively eliminated” through fiscal discipline.

Today, one could not hear such talk. Record deficits are the bipartisan norm. They occurred under all four 21st century presidents (George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden). National debt now exceeds $33 trillion, an all-time high. Bernanke terms Greenspan’s approach “analytical error.” Bernanke’s successor at the Fed, current Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen (2014-18) argued against zero inflation as an academic and has defended deficits.

Keynesian economics has dominated fiscal policy since the Great Depression. Traditional Keynesian economics prescribes surpluses in economic expansions, and deficits in recessions. In recent decades, bipartisan practice has been to deliver deficits in both expansions and recessions. More significantly, deficits have grown at alarming rates.

The historical dimension is that Americans contested monetary policy for a majority of U.S. history. How was it possible, one might ask, for citizens to debate an issue deemed “too technical” in our own time? Dissenters included U.S. presidents. Thomas Jefferson argued a central bank would cater to financial interests to the detriment of agriculture. Andrew Jackson vetoed a central bank bill in his first term, and signed a law that required gold payment of federal debts is his second. The Democrats were the party of sound money for most of the 19th century. Grover Cleveland is the premier example, defending the gold standard against inflationists in his own party, including William Jennings Bryan. The Fed was created under another Democrat, Woodrow Wilson. His Republican predecessor, Theodore Roosevelt, had called for a more elastic currency. In 1933, Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the U.S. off the gold standard. In 1971, Republican Nixon severed the final link between the U.S. dollar and gold.

Today, it is unusual for presidential candidates to discuss monetary policy, let alone to dissent from Federal Reserve policies. One exception is former congressman Ron Paul of Texas, author of a 2009 New York Times best-seller on the topic, End the Fed. The latter suggests Americans seek renewed debate on monetary policy. With inflation at four-decade highs, they have practical reasons to question policies.

Forests have been felled to satisfy economists’ academic arguments about inflation. There is an entire literary subculture on the topic. Your member of Congress blames the other party. Mass media leaves you unfulfilled given that most journalists are intimidated by the topic. The most unexpected solution is to consult the Fed directly. It is available to us seven days a week, 24 hours a day. Once upon a time, access to a university library was required to read all Fed member bank reviews. The Internet has made that trip unnecessary. The good news is that, armed with such information, Americans have the tools available to contest monetary policy at least as effectively as Americans of earlier eras did. Monetary policy is not just an economic issue for experts to debate. Americans should make it a political issue their politicians feel compelled to address as well.

Informed Americans also are in a better position to develop plans to protect their families against the ravages of inflation than ever before. These plans include household budgets based on best-to-worst case inflation scenarios, substitution, and learning from elders who survived earlier inflations.

True understanding of the inflation problem comes from listening to our fellow citizens. On a recent visit to West Memphis, I learned about diesel fuel inflation from truck drivers, labor shortages from restaurant managers, and rising food costs from waiters and waitresses. Such anecdotal information can be more important to building a general understanding of our situation than models built by Ph.D. economists. Others have their own unique observations. In one sense, households have an advantage. They are humble and willing to learn.

By contrast, central planners are confident, even arrogant, but it is beyond them, and beyond the capacities of any human being, to centrally plan an economy as complex as that of the United States, without messing things up. American would be wise to prepare for the worst, and not to assume central bank officials will eat humble pie and alter course when events prove them wrong.

Chronicles Executive Editor Edward Welsch contributed to this article.

Leave a Reply