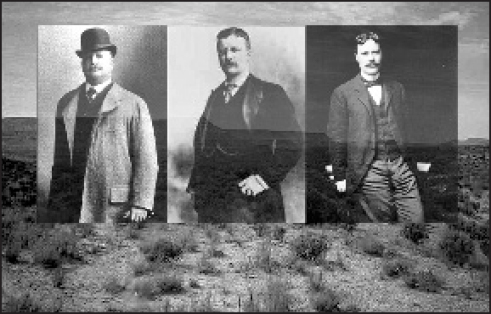

During the first half of the second-to-last decade of the 19th century, three young gentlemen traveled from their native region of the northeastern United States to the trans-Mississippi West, still a few years short in those days of the official closing of the American frontier. Though alike in being Ivy Leaguers, well-born, well-bred, and well-heeled, the three were otherwise dissimilar in background and training, as well as in character and temperament. The eldest (though only by a year), born at Oyster Bay, New York, and educated at Harvard College, having published an ornithological work and a history of the War of 1812, had already made up his mind on a political career when he entrained for the Dakota Territory in 1883 for health reasons—and in hope of shooting a buffalo “while there were still buffalo left to shoot.”

The second in age was a Philadelphia patrician, descended on his mother’s side from Pierce Butler of South Carolina and Fanny Kemble, the renowned Shakespearean actress, whose aspirations to a career as an operatic composer had resulted in his meeting Richard Wagner at Bayreuth and, in Wagner’s house, Franz Liszt (who, after listening to an original composition by the young man had complimented him on a “talent prononcé”) before his return to Philadelphia to take a job with the Union Safe Deposit Vaults. A graduate of Harvard (and later of Harvard Law School), he was a close friend of the Oyster Bay man, whose enthusiastic tales of Western life influenced him in his decision to spend the summer of 1885 in Wyoming, for reasons of his own health.

The third youth, less distinguished socially and hailing from the modest town of Canton in upstate New York but a Yale graduate all the same, was a year younger yet. A former forward on the Yale football team who had studied art in college, he went west in 1881 for the explicit reason of “becoming a millionaire” and, thus, eligible for the hand of the young lady in Ogdensburg, New York, already refused him by her father. The names of these three young gentlemen were Theodore Roosevelt, Owen Wister, and Frederick Remington.

What each discovered in the West differed according to his temperament and intellect. In the case of two, the direct experience of the Western frontier provided a sense of vocation; for the third, it served to distinguish between vocation and avocation, while developing the physical and mental strength demanded by a career in politics whose aim, even at so early a date, was the White House. Inevitably, according to their natures, each of the three men entertained a differing vision of the future of the American West, as well as of its past. What they shared in experience was a vital apprehension of the West as it presented itself to their exuberant youth, the embodied manifestation of the clean bedrock reality—unsentimental, unsparing, and irresistible—upon which human existence rests, even as they understood, with regretful pangs, that the reality they knew was already on the wane and would perhaps be gone as soon as tomorrow, or the day after. What they won by experience was also a shared achievement. This was nothing less than manhood, a fact that all three—Roosevelt, Wister, and Remington—appear to have recognized intuitively.

Perhaps realizing, early in adulthood, one’s childhood dreams is the most direct and best route to developed maturity. Then again, perhaps it is not—in the Land of Opportunity especially, where getting what they want before the age of 30 may be the most efficient means of depriving so many Americans of their lives’ second acts, as Scott Fitzgerald suggested. What is notable in the instance of Remington, Wister, and Roosevelt is that they seem to have had no previous idea, entertained no preconceived ideal, of the reality that, in its taking hold of them and their taking hold of it, received them as youths and sent them forth as men. Remington’s initial inspiration was the prospect of making millions—that, and the example of his father’s service as a soldier in the War Between the States. Roosevelt wanted to shoot a buffalo. And Wister wanted to escape his bank; later, Harvard Law School; and, later still, the practice of law. In each case, the ideal was to follow later: manly endurance, fortitude, and physical competence (Roosevelt); Anglo-Saxon chivalry (Wister); and “the subject,” explored, set down, and preserved by the recording of “facts” selected from the endlessly unfolding “panorama” of the life of the American West (Remington).

In due time, their three separate (though substantially overlapping) ideals did materialize—but on location, not at a distance and in absentia. The following passages give an impression of the nature and quality of these. From Remington:

Evening overtook me one night in Montana and I by good luck made the campfire of an old wagon freighter who shared his bacon and coffee with me. I was 19 years of age and he was a very old man. Over the pipes it developed that he was born in western New York and had gone West at an early age. His West was Iowa. Thence during his long life he had followed the receding frontiers, always further and further West. . . .

I knew the railroad was coming. I saw men already swarming into the land. . . . I knew the wild riders and the vacant land were about to vanish forever—and the more I considered the subject, the bigger the forever loomed.

From Wister:

I can’t possibly say how extraordinary and beautiful the valleys we’ve been going through are. They’re different from all things I’ve seen. When you go for miles through the piled rocks where the fire has risen straight out of the crevices, you never see a human being—only now and then some disappearing wild animal. It’s like what scenery on the moon must be. Then suddenly you come round a turn and down into a green cut where there are horsemen and wagons and hundreds of cattle, and then it’s like Genesis. Just across this corduroy bridge are a crowd of cowboys round a fire, with their horses tethered.

And from Roosevelt:

When the days have dwindled to their shortest, and the nights seem never-ending, then all the great northern plains are changed into an abode of iron desolation. Sometimes furious gales blow out of the north, driving before them the clouds of blinding snowdust, wrapping the mantle of death round every unsheltered being that faces their unshackled anger. They roar in a thunderous bass as they sweep across the prairie or whirl through the naked cañons; they shiver the great brittle cottonwoods, and beneath their rough touch the icy limbs of the pines that cluster in the gorges sing like the chords of an Aeolian harp. . . . All the land is like granite; the great rivers stand still in their beds, as if turned to frosted steel. In the long nights there is no sound to break the lifeless silence. Under the ceaseless, shifting play of the Northern Lights, or lighted only by the wintry brilliance of the stars, the snow-clad plains stretch out into dead and endless wastes of glimmering white.

Then the great fire-place of the ranch house is choked with blazing logs, and at night we have to sleep under so many blankets that the weight is fairly oppressive.

Ideals, derived as they are from the moral imagination, are not mere abstractions; nor are they entirely detached from the chronological and social contexts in which they were formed, and which partly formed them. Roosevelt, Wister, and Remington: All three, as old-line Americans, were, to a greater or lesser degree, and in their different ways, dismayed by the direction their country was taking and the shape it was assuming. After meeting Remington for the first time in the lodge at Geyser Basin in Yellowstone Park, Wister rejoiced at having found a kindred spirit (one who, by great good fortune, was already signed on as his collaborator):

Remington is an excellent American; that means, he thinks as I do about the disgrace of our politics and the present asphyxiation of all real love of country. He used almost the same words that have of late been in my head, that this continent does not hold a nation any longer but is merely a strip of land on which a crowd is struggling for riches.

By coincidence, not many days before making the artist’s acquaintance, the novelist-to-be had written that he saw no escape from the saturnalia of American politics: “Our country and its government are now two separate things, not greatly unlike a carcass and a vulture.” This fate, which Wister noted had befallen great nations before in history, entailed its own remedy, which was simply the caving in of all business credit and a collapse of the trust that makes credit available. “I hope this earthquake will come as soon as possible . . . for this is our only hope. No preaching or protest, no honest young men entering politics are going to be of the slightest avail now.” To most of Remington’s and Wister’s assessment, the young Roosevelt would doubtless have assented—the final sentence excepted. “I intended,” he wrote later (but not much later), “to be one of the governing class.” He was a young man already entered in politics, and he intended to be very much of avail in charting a new course for the burgeoning American nation.

Three differing viewpoints on broader matters resulted in three equally differing attitudes with regard to the future of the American West (and, ultimately, of America herself). Remington’s reaction to the fact of historical ephemerality was a carpe diem response: Get as much of it down—on paper, in paint, and in bronze—as possible in a single lifetime (which, in his case, was only 48 years). For Remington, technique was his subject, as well as the means of rendering it: Skill, competence, agility, and “grace under pressure,” on the part of brute creatures as well as of men and women, are really what his work records and celebrates, rather than the West itself. (Critics have observed that the drawings and paintings leave the natural background vague or nonexistent, quite unlike those of Remington’s equally great contemporary, C.M. Russell.)

Wister’s response was more complex. His famous postprandial declaration, made at the Philadelphia Club in 1891 after a return from a Western sojourn, of his intent to become the Kipling who would save “the sage-brush for American literature,” was actually preceded by the more intellectual, writerly reaction. “I feel more certainly than ever,” he had written in his journal on that first trip to Wyoming, “that no matter how completely the East may be the headwaters from which the West has flown and is flowing, it won’t be a century before the West is simply the true America, with thought, type, and life of its own kind.” Two entries later, he qualifies his seeming enthusiasm by adding, “it will slowly make room for Cheyennes, Chicagos, and ultimately inland New Yorks—everything reduced to the same flat prairie-like level of utilitarian civilizations. Branans and Beeches [i.e., ranchers and homesteaders] will give way to Tweeds and Jay Goulds—and the ticker will replace the rifle.” In the case of Roosevelt, however, we find a more equivocal note in his contemplation (in Ranch Life and the Hunting Trail) of the passage of time, change, and the unfolding of history:

In its present form stock-raising on the plains is doomed, and can hardly outlast the century. The great free ranches, with their barbarous, picturesque, and curiously fascinating surroundings, mark a primitive stage of existence as surely as do the great tracts of primeval forests, and like the latter must pass away before the onward march of our people; and we who have felt the charm of the life, and have exulted in its abounding vigor and its bold, restless freedom, will not only regret its passing for our own sakes, but must also feel real sorrow that those who come after us are not to see, as we have seen, what is perhaps the pleasantest, healthiest, and most exciting phase of American existence.

The man of affairs who already half-expected to get himself elected president of the United States was able to accept, with equanimity, the passing of the West with which he had fallen in love. As for the man of letters and the artist (a talented writer himself), the two found historical bottom in the notion of the American cowboy as an unchanged and unchanging type, once Remington had succeeded in diverting Wister from his evolutionist theories regarding the West in process of becoming the “true America.” As Wister put it in his essay “The Evolution of the Cow-Puncher,” “in personal daring and in skill as to the horse, the knight and the cowboy are nothing but the same Saxon of different environments”—as were the Hawkinses, Boones, and Greys—“always the same Saxons, ploughing the seas and carving the forests in every shape of man, from preacher to thief, and in each shape changelessly unchanged.” (That his “evolution” was actually evolution’s antithesis seems not to have occurred to Wister: Evolution was the idea that had set off his theorizing about the West, and so it was “evolution” he acknowledged in his title.)

Roosevelt, Wister, and Remington responded with equal passion, engagement, and imagination to the Western frontier, which all three saw as a Beginning, in the sense of a primeval basis (Roosevelt, like Wister, compares the landscape of the West to that of Genesis), though only one of them recognized it as the End that would form the basis of a New Beginning. In so responding, they became, in equal measure, men. But there was something more as well, since their manliness developed in conformity with a distinct type of man: man as the West had made him, and as it might make American men in the future, provided they succeeded in combining the strenuousness of T.R. with the artistic vision of Frederick Remington and the chivalric code of Owen Wister. The great question was, Could the desired ideal be sufficiently realized, given the human material at hand in America at the turn of the 20th century? Of the three, only The Man Who Would Be President seems to have believed there was so much as a remote possibility of the thing being accomplished at all.

As early as 1894, in his essay “Americanism” (in Forum), Theodore Roosevelt derogated “that flaccid habit of . . . cosmopolitanism” at the expense of a distinctive American type forged from “Americanized” immigrants and Old Americans who had refused the temptation to throw their birthright away. A year later, the historical pessimist Owen Wister lamented (in “The Evolution of the Cowboy”) that “No rood of modern ground is more debased and mongrel with its hordes of encroaching alien vermin, that turn our cities to Babels and our citizenship to a hybrid farce, who degrade our commonwealth from a nation into something half pawn-shop, half broker’s office.” For most of the 20th century’s first decade, Roosevelt was ensconced in the White House behind his bully pulpit, striving lustily to Americanize America in accordance with his vision. Frederick Remington died prematurely in 1908. Even before 1914, Wister, under the influence of his friend John Jay Chapman, became, in John Lukacs’s description, “a racist of sorts,” “brood[ing] endlessly about how immigration was destroying the nation.” Where Roosevelt advocated Americanization, Wister wanted Restrictionism. Neither solution worked in the end, chiefly, perhaps, for a reason Roosevelt had put his finger on in Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail:

To appreciate finally his fine, manly qualities, the wild rough-rider of the plains should be seen in his own home. There he passes his days, there he does his life-work, there, when he meets death, he faces it as he has faced many other evils, with quiet, uncomplaining fortitude. Brave, hospitable, hardy, and adventurous, he is the grim pioneer of our race; he prepares the way for the civilization before whose face he must disappear. Hard and dangerous though his existence is, it has yet a wild attraction that strongly draws to it his bold, free spirit. He lives in the lonely lands where mighty rivers twist in long reaches between the barren bluffs; where the prairies stretch out into billowy plains of waving grass, girt only by the blue horizon,—plains across whose endless breadth he can steer his course for days and weeks and see neither man to speak to nor hill to break the level; where the glory and the burning splendor of the sunsets kindle the blue vault of heaven and the level brown earth till they merge together in an ocean of flaming fire.

In order to be appreciated—and, thus, emulated—the prototypical Westerner needed to be viewed in the context of his own pristine habitat. And what had become, by the end of the frontier century, of that habitat? On this matter, Roosevelt, Wister, and Remington all could have agreed. The entire business may be as simple as that.

Leave a Reply